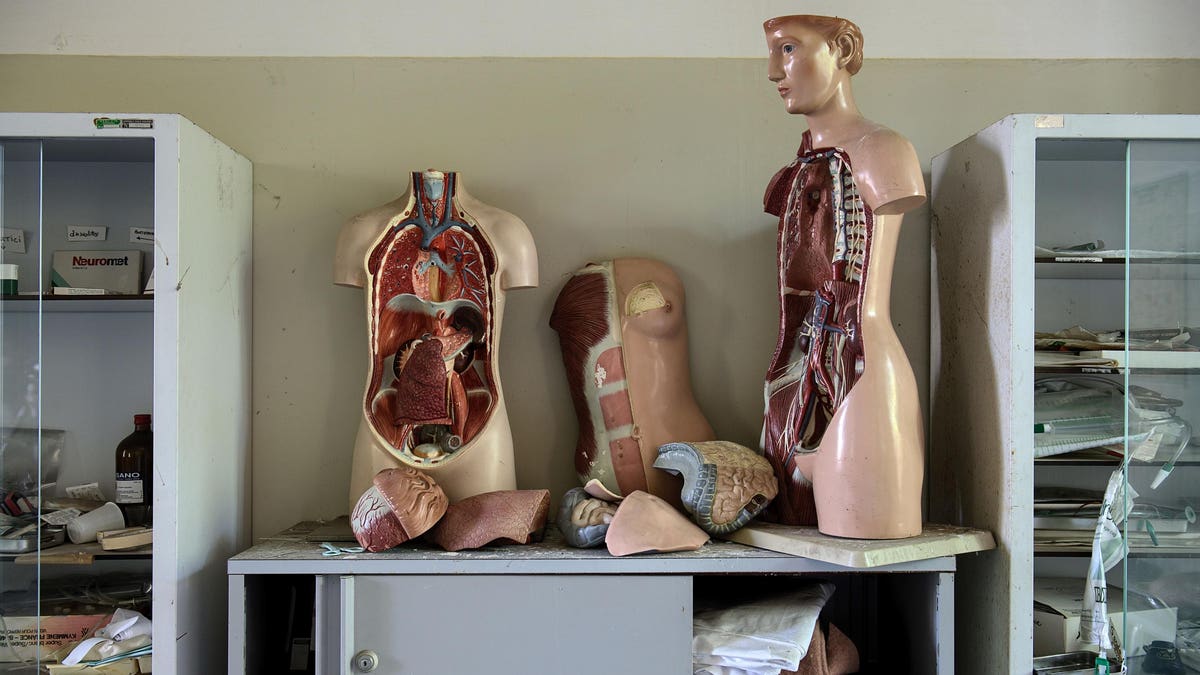

White, 20-30 years old, 70-kilogram (154-pounds), and 170 cm (about 5 feet 7 inches) tall, the Reference Man has been a staple in society since 1975. At the time, it was a landmark composite of heterogeneous data from different geographies, populations, and races: the first “serious attempt to compile detailed body composition data”. While it was originally used to help understand what levels of radiation, both internal and external, were safe, the Reference Man is still used today for a variety of purposes; it serves as a lessons in anatomy studies, such as those in medical school classes, as a dimension reference for seat designs, and as a standard against which organ sizes can be compared in transplant cases. Since women were considered to be small men with different reproductive organs until about 1991, the Reference Man was used to represent them as well; reproductive organs were swapped in and out of it to represent men and women alike.

In the almost 5o years since the creation of the Reference Man, however, both sex- and gender-based medicine and women’s health have come into the spotlight and belied the idea that a man can serve as a universal reference. Sex and gender medicine (SGBM) is the understanding that sex and gender are significant determinants of certain health conditions and treatments while women’s health is based around the fact that women are not just small men – and that their sex means that they can experience certain health conditions and treatments differently from men in the first place.

And yet, medical education, practice, and research still remains based on the Reference Man, which doesn’t account for these sex-based differences, even the most basic physiological ones. For example, women tend to be smaller and shorter than men are. The average women today is 77.1 kilograms (over 170 pounds) and 161.8 cm (5 foot 4 inches) tall: about seven kilograms (about 16 pounds) heavier and nine centimeters (three inches) shorter than the Reference Man. Women typically also have a higher percent of body fat, less bone mass, less muscle mass, narrower airways, smaller lungs, smaller and thinner bones, and smaller voice boxes than men do – as well as having differences that can’t necessarily be illustrated by a physical reference model, such as blood pressure, resting heart rates, and volume of certain brain regions to name a few. The Reference Man as is doesn’t represent those unique traits, and, thus, those sex-based differences.

Ironically, the Reference Man doesn’t necessarily represent the average man either. The average male in the United States today is 89 kilograms (196.9 pounds) and 175.5cm (about 5 feet 9 inches) tall: 19 kilograms (almost 42 pounds) and five and a half centimeters (two inches) taller than the Reference Man. And while the Reference Man has a body mass index (BMI) of 24.1kg/m², the average male in the United States’ BMI is 26.6 kg/m² and the average woman’s is 26.5 kg/m². One article about obesity rates was titled “In Search of the 70kg Man” to highlight the discrepancy in just weight alone – much less height and BMI – between today’s average man and the Reference Man.

In short, the Reference Man needs to be updated with models that better represent today’s average man and average woman than this almost half-century-old “standard”. But only in 2022 was the most advanced female model, a potential Reference Woman, built in entirety. A corresponding press release noted that, with this new female model, “educators can choose the sex with which they’d like to teach their full curriculum in addition to having the option of switching between male and female anatomies to teach comparative differences in sex-specific regions of the body” – rather switching different reproductive organs in and out of a single male body.

The prior lack of a “Reference Woman” is not the only way that women’s health has been overlooked at educational institutions, though. In a survey conducted from 1994 to 1995, only 14% of surveyed medical schools reported having a women’s health curriculum, 28% offered a clinical rotation in women’s health separate from a traditional obstetrics/gynecology clerkship, and 10% had an office or program responsible for integrating women’s health and sex/gender-specific information into the curriculum. By 2000, 33% of surveyed schools had an office and/or program integrating and overseeing women’s health and sex and gender differences in the curriculum: a huge increase in theory but one that remained limited in practice. Despite the increase in these offices and programs, only 30% of schools in 2004 did, in fact, have a corresponding curriculum that covered sex and gender-specific topics.

A 2011 survey of 44 medical schools in the United States and Canada echoed the results from 2004, finding that 70% still did not have a formal sex- and gender-specific integrated medical curriculum. Similarly, multiple studies have found that students believe their education around gender- and sex-based medicine – and women’s health specifically – to be lacking. In 2016, a survey of medical school students found that 94.4% believed SGBM should be included in a medical school curriculum while 70% of respondents in another survey that same year indicated that gender medicine concepts are never or only sometimes discussed or presented in their training program.

As a study published in 2016 concluded, “We must assist current health professionals in recognizing the increasing body of knowledge around sex and gender differences, and even more so, passing this knowledge to future providers”. The study authors also added that their results “should encourage ongoing commitment of US medical school leadership, professional organizations, learners, accrediting bodies, and other stakeholders to close the sex and gender medicine gap in our current curricula”.

Having a curriculum – and appropriate reference models – for men and women, though, can improve not only healthcare learning and practice but also designs and innovations that have historically been based on men. Chairs, cell phones, and personal protective equipment (PPE) that are sized for men’s comfort may be too big for women (and, in the case of PPE, may render it completely ineffective as well as inconvenient). Vehicles that are manufactured with relatively limited safety padding around the headsets may protect men adequately but may put women at an increased risk of injuries such as whiplash since women have smaller and weaker supporting muscles in the cervical spine and less body weight for back support than men do.

The Reference Man that is still used now is stuck in the 70s. Replacing it – creating and using models that represent today’s average man and woman distinctly – can help challenge the idea that a man should be the universal reference, offer a female reference, and maybe even start eliminating the subsequent and pervasive male bias: in healthcare and otherwise.

Read the full article here