Despite his proverbially happy attitude, John Waters admits that he’s currently experiencing a little bit of sadness.

He’s missing his parents.

“I wish they could be here because they always made me believe that I could do whatever I wanted to do, even though they were horrified by what I was doing,” he explains.

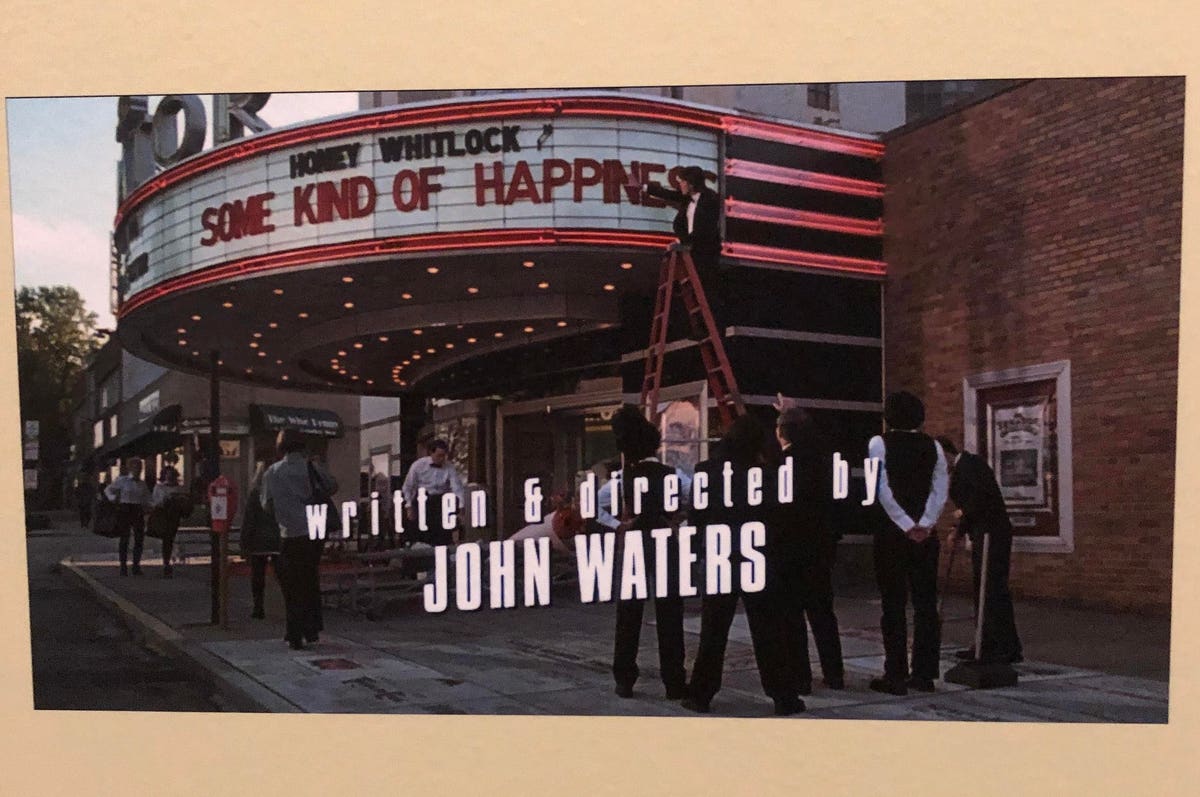

Known for forever challenging the notion of ‘good taste,’ Waters, over the course of his six decade career, has created a cavalcade of cringe-worthy, yet high entertaining films. Through his continued unconventional envelope-pushing, Waters has cemented his status as one of the most respected independent filmmakers in history.

Now Waters’ contributions to cinema are being celebrated with a new exhibit at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures.

And he’s wishing his parents were still alive to see this, along with his newly unveiled star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

The new exhibit, John Waters: Pope of Trash, includes never before displayed objects from Waters’ personal collections, interactive elements, an extensive retrospective film series, an exhibition catalogue, and exclusively licensed merchandise.

The exhibit embodies Waters’ paradoxically serious attitude about issues intermingled with his campy storytelling sensibility, taking visitors through a menagerie of his films, including, but not limited to, Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1974), Hairspray (1988), Serial Mom (1994) and A Dirty Shame (2004).

Exhibitions Curator Jenny He, says in the early stages of creating the exhibit her team focused on how best to satisfy hardcore fans of Waters who have intimate knowledge of all his work, as well as those who are only tangentially aware of the man, having seen the impeccably dressed, thin mustached Waters in numerous cameos in television and movies, along with individuals who aren’t at all familiar with the enigma that is John Waters.

To do this, He explains how the exhibit begins with a dramatic entrance gallery which is “ basically a movie theater in an abstracted church setting, because John premiered his early films churches.”

Then, He says, “We also looked at, of course, the recurrence of music and dance throughout [Waters’] films, and we have a gallery called The Musical Interlude, which fittingly falls between Hairspray (1988), [which is Waters’] dance film, and Cry Baby (1990), [Waters’] musical.”

Closing out the exhibit, she says, is a tribute to Waters’ fans, that, “very much speaks to the core group who have followed [Waters’] career for the last 60 years.”

The process of locating and assembling all of the 400 items featured in the collection felt, ‘like detective work,’ says Associate Curator Dara Jaffe.

She says that the team’s first stops were Waters’ personal collection that he keeps in his hometown of Baltimore, as well as archives stored at Wesleyan University and Yale University.

“Between these collections, you’re really going through a careers worth of production materials, and the life’s work of [Waters’] personal writings and research and clippings. But, then at the same time, as you do your digging, you find new stories, you go down rabbit holes, find new obsessions, and you add those stories to the narrative as well.”

Jaffe says that one item that they’re especially proud of was retrieved when the museum team went door-knocking on the street where Waters filmed 1981’s Polyester. She explains that there was one neighbor who still lived there and who donated a bar cart used in the movie.

At hearing this, Waters quips that when they were shooting Polyester, some of the neighbors went to extreme measures to get him to stop filming. “The nice ones were in the movie. The mean ones sued,” he revealed.

Another treasured item on display, one that was recreated, is the trailer from the film Pink Flamingos. In a twist, visitors can actually sit in the trailer and watch the trailer for the film, which itself is as unique as all of Waters’ creations.

Once all of the artifacts had been collected, He says that, “we worked very, very diligently with our exhibition, design, and production teams, with our collections and conservation teams, to realize the curatorial vision in the spatial experience.”

Jaffe says that all of the elements play into the themes examined by Waters via his films, which include, but aren’t limited to, “infamy, crime in courtrooms, outsiders to polite society with very specific subcultures, domesticity — especially along class lines — protest, and I think always approached winkingly by [Waters] with satire.”

She adds that, “you will see both real clippings going back to the ‘60s and ‘70s that inspired John [in his storytelling], and you will see prop newspapers as well.”

(Waters is known for reading up to 20 newspapers a day, gleaning stories from their pages.)

This links back to the repeated theme of infamy, which is so present in nearly all of Waters’ works, says Jaffe, stating that in Waters’ world, “if you’re in the news, you’re newsworthy, and for so many of John’s characters, that is the end goal, no matter what it takes.”

Upon hearing this, Waters refers to his parents again, saying, as he drops his head a bit, looking out the top of eyes, speaking with a perfect cadence, that, “my mother once told me when I was young, she said, ‘Fools names and fools faces always appear in public places.’”

Speaking again with just the right phrasing, Waters says that he hopes that what people will take away from the exhibit is, “A sense of humor that knows that we never make our enemy feel stupid. We make them feel smart even, then get them to laugh and then we can get them to listen.”

‘John Waters: Pope of Trash’ is now open at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures and runs through August of 2024.

The Museum is located at 6067 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90036. For more information, please visit this website.

Read the full article here