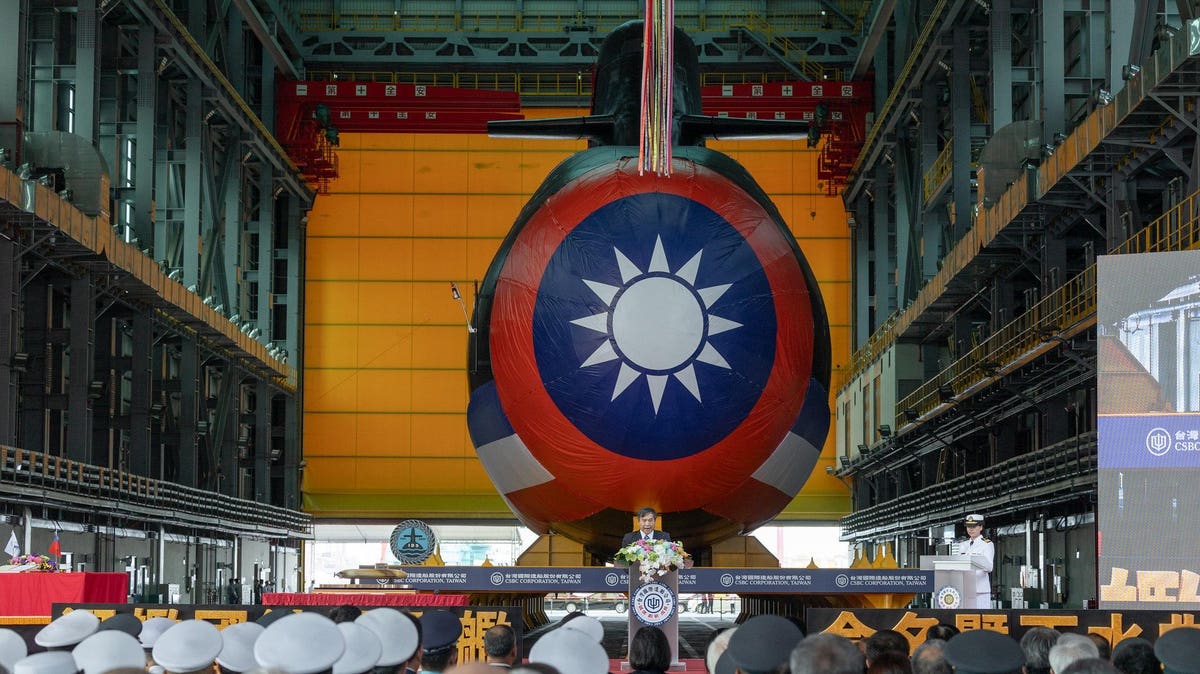

Taiwan christened its first homemade submarine on Thursday. It’s the culmination of a crash effort that began in 2014, has cost potentially billions of dollars and reportedly has involved extensive—and largely secret—foreign assistance. The next boat in the class could launch in around four years.

The 2,600-ton Hai Kun—named for a mythical giant fish—by far is the most important new weapon in Taiwan’s arsenal.

More than F-16 fighters, M-1 tanks or Patriot air-defense missiles, Hai Kun and her planned seven sisters could blunt a Chinese invasion. And fighting alongside submarines belonging to the United States—and potentially Japan—they even could defeat the invasion.

That’s because after firing hundreds of ballistic missiles and cruise missiles at Taiwanese defenses and severing the island country’s supply lines and telecommunications, the Chinese navy and its civilian auxiliaries still must cross the 100-mile-wide Taiwan Strait to land troops and vehicles on Taiwan’s western beaches—or sail hundreds of miles around the island to land on its eastern coast.

When it’s on the water, the invasion force is extremely vulnerable. And even if it manages to land some of its troops, it remains vulnerable. For the first critical weeks of a Chinese ground campaign in Taiwan, Beijing’s brigades will depend on ships for resupply.

Sink enough of the landing ships, or enough of the supply ships, and the invasion collapses—either at the beach, or farther inland as landed forces starve. While Taiwan’s surface ships and F-16s with their Harpoon anti-ship missiles pose some threat to the Chinese fleet, submarines firing 3,700-pound Mark 48 torpedoes are much more dangerous.

Back in January, the Center for Strategic and International Studies gamed out a Chinese invasion of Taiwan in a series of realistic simulations. The results depended heavily on how much surprise China achieved and how carefully the United States dispersed its forces in the western Pacific in advance of the initial Chinese missile barrages.

But in most of the 24 scenarios, the Taiwanese and their allies ultimately prevailed—albeit at enormous cost in people and equipment. And when they prevailed, it was because of two key weapons: submarines and bombers.

In a majority of the simulations, “submarines were able to enter the Chinese defensive zone and wreak havoc with the Chinese fleet,” CSIS analysts Mark Cancian, Matthew Cancian and Eric Heginbotham concluded.

The U.S. fleet’s 40 or 50 attack submarines would organize in squadrons of four boats apiece and deploy to U.S. bases in Guam, at Wake Island and in Yokosuka, Japan. One squadron would be on station in the narrow Taiwan Strait when the first Chinese rockets fell and the invasion fleet set sail.

In CSIS’s war games, those four boats sank Chinese ship after Chinese ship until their torpedoes and missiles ran out or Chinese forces hunted them down. The other nine or 10 USN sub squadrons meanwhile synchronized into what the Cancians and Heginbotham described as an undersea “conveyor belt.”

“They hunted, moved back to port, reloaded, then moved forward again and hunted,” the analysts explained. “Each submarine would sink two large amphibious vessels (and an equal number of decoys and escorts) over the course of a 3.5-day turn,” the Cancians and Heginbotham wrote.

In two weeks of intensive fighting in the simulations, the submarines sank as many as 64 Chinese ships, including many of the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s biggest amphibious ships and surface combatants—and potentially some of the PLAN’s aircraft carriers, as well.

The Chinese ships that succeeded in avoiding American submarines weren’t safe, of course. The CSIS war games found that U.S. Air Force bombers firing stealthy cruise missiles posed an even greater danger to Chinese ships than did U.S. Navy subs.

In the scenario where the Taiwanese and their allies won most decisively, the Chinese amphibious and transport fleet lost 90 percent of its ships—and was unable to supply the few Chinese battalions the fleet had managed to land on Taiwan. With no sea lines of communication, Chinese troops on the island quickly ran out of fuel and ammunition.

What’s telling is that the CSIS war games didn’t include a significant Taiwanese submarine force. The Republic of China Navy does possess two front-line submarines that pre-date Hai Kun and her planned sisters. But these two, 2,700-ton vessels—which The Netherlands built for Taiwan back in the 1980s—generally are considered obsolete.

Adding the eight Hai Kuns to an American-led undersea campaign around Tawain should expand, by a fifth, the number of boats and torpedoes the defensive alliance can deploy against the Chinese fleet. Add in some of Japan’s 22 submarines and the undersea force becomes even more powerful.

Victory could come at a high cost for American, Japanese and Taiwanese submariners, of course. In CSIS’s war games, Chinese escorts, aircraft and submarines usually sank around a fifth of the deployed subs every three or four days throughout the weekslong war. In the end, perhaps a dozen or more subs lay wrecked at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, tombs for thousands of submariners.

Taiwan could lose several of its new submarines defeating a Chinese invasion. But that’s a small price to pay to save the island democracy.

Read the full article here