Editor’s Note: Editor’s Note: This story was originally published on June 6, 2017. It has been updated and republished following Dianne Feinstein’s death on Friday at age 90.

I will never forget standing outside Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s office in December 2014 and seeing her husband, Richard Blum, coming down the hallway. As he walked in, I asked him, “You know your wife is a badass, right?” He looked at me, surprised and a bit confused, until I quickly assured him that was a compliment.

It was the first time I used the term “badass” to refer to a woman in Washington, especially to her husband, but it was well-deserved. He had come to support his wife as she was about to do something courageous and controversial: defy the leader of her party, President Barack Obama, by publicly releasing a classified summary of a report she spearheaded as Senate intelligence chairwoman on post-9/11 enhanced interrogation tactics by the US government.

Obama and many in the intelligence community were staunchly against releasing any of the report, insisting it would jeopardize national security. Feinstein argued it was critical for America to learn about what she called “an ugly truth” in order to avoid repeating it. She is still working today on making the entire report public, not just the summary.

“It was six years of work, it was staff that worked, you know, night and day, weekends on this. The report itself is over 7,000 pages, over 32,000 footnotes. And we are trying to protect it now to keep it from being destroyed,” she said.

That was just one of many topics we discussed when the senator invited us to her San Francisco home in 2017 to reflect on five decades in politics and public service that made her an icon – one of the pioneering badass women in Washington who fought their way into an overwhelmingly male power structure and figured out how to stay there. Feinstein, 90, died Thursday night at her home.

Feinstein’s trajectory to the Senate began with a double murder inside San Francisco City Hall.

Feinstein rarely talks about the day 40 years ago when Mayor George Moscone and Harvey Milk, the first openly gay politician in America, were shot and killed. But she opened up with us in excruciating detail.

She was on the San Francisco board of supervisors then, and assassin Dan White had been a friend and colleague of hers.

“The door to the office opened, and he came in, and I said, ‘Dan?’”

“I heard the doors slam, I heard the shots, I smelled the cordite,” Feinstein recalled.

“He whisked by, everybody disappeared. I walked down the line of supervisors’ offices. I walked into one and found Harvey Milk – put my finger in a bullet hole trying to get a pulse. But you know, it was the first person I’d ever seen shot to death, and you know when they’re dead,” she said.

Feinstein said she has always wondered whether she could have prevented the murders.

“I was a friend of Dan’s, and I tried to some extent to mentor him, and he was a former police officer, a former firefighter. Very good-looking, young, robust man.”

While telling the story, Feinstein stopped herself, looked down, and let out an audible “ooph,” explaining apologetically, “I never really talk about this.”

“Dan had resigned and then wanted the seat back, and so he had an appointment with the mayor, and he walked into the office. And they had a meeting in the back office, and he shot him a number of times.”

It was Feinstein who announced the double assassination to the public and revealed that White was the suspect. Then she was sworn in as the first female mayor of San Francisco.

By that time, she had already broken one glass ceiling, becoming the first female chair of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. During that time, Feinstein ran twice for mayor but was defeated both times. After tragedy put her in the job, she was elected in her own right and served as mayor for 10 years.

Politics was not exactly the path most of her female classmates at Stanford University in the 1950s considered pursuing.

“Something must be wrong with her, she must have a bad marriage, why is she doing this,” Feinstein recalled people saying about her.

“Look, being a woman in our society even today is difficult,” she told me. “And you know it in the press area, I know it in the political area.”

But she worked hard as mayor to overcome questions about whether a woman was up to the job.

“I went to every fire over three alarms in the city,” she said, showing me a hard hat the fire department gave her.

“I had a radio in my room, in my bedroom,” she said, so she could hear in real time about fires.

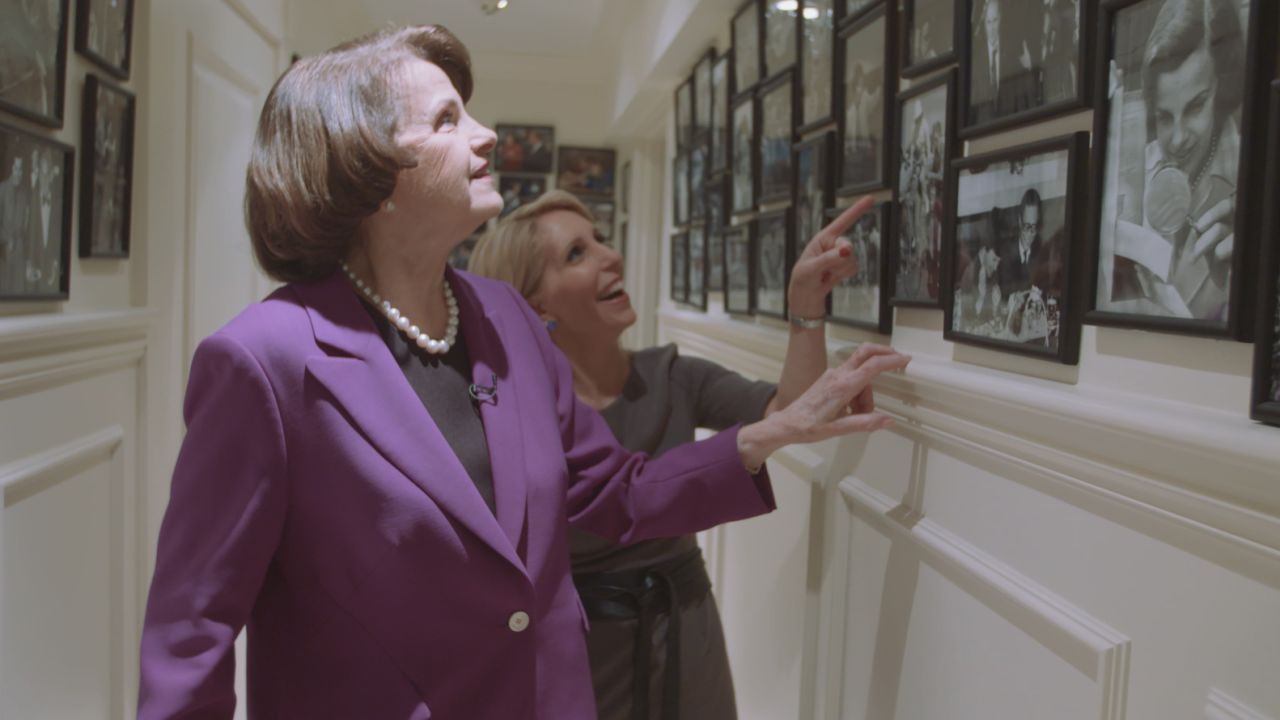

That hard hat is one of hundreds of mementos and photographs Feinstein saved and put on display behind glass cases and on the walls in a special room inside her San Francisco home.

To tour it with her is to take a stroll not just down Feinstein’s memory lane, but the modern history she helped shape and celebrate: photographs of San Francisco visits of Pope John Paul II and Queen Elizabeth II that she had a leading role in planning, plus memorabilia from the 49ers football team, in their heyday when she was mayor.

One picture, however, was a powerful reminder that her political tenure was hardly gender neutral. It is a photo of Feinstein wearing a bathing suit in October 1978 while she was president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.

The story? A developer bet her that if he finished a project on time, she would have to wear a bathing suit in public. She took the bet, and he won.

She and her husband found an old-fashioned bathing suit that covered her up as much as possible. She still has it – and preserves it in a plastic bag to keep away the mothballs.

Amid the awards and accolades she has collected over the decades was an edition of People magazine from 1984 with Feinstein on the cover. Time magazine did a cover shoot with her, too.

The inside scoop, she explained, was that the magazines were preparing in case she was chosen as Walter Mondale’s vice presidential running mate that year.

“The blonde or the brunette for vice president for Mondale,” she recalls about the way it played back then. “They thought I was going to get it.”

But in the end the blonde, Geraldine Ferraro, was Mondale’s pick.

When I asked Feinstein why she never ran for president, her response surprised me, given how much she has accomplished.

“I don’t know. I felt I’d never be elected. See, look how hard it is, look at Hillary [Clinton]. I mean, look at what she’s gone through,” Feinstein responded wistfully.

“You’ve done hard before,” I countered.

“Yeah, I’ve done hard before, but it – it’s not a bad thing being in the Senate,” she said.

Not bad at all for Feinstein. California’s first woman sent to the US Senate in 1992 racked up many other firsts as she became a DC powerhouse. She was the first woman to sit on the Judiciary committee, the first female chairwoman of the Rules Committee, first woman to co-chair the inaugural committee – and the first female chair of the Senate intelligence committee.

As a new member of that committee in 2002 and 2003, she said she read, and believed, assessments that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. Because of that, she voted for the Iraq War, which she calls one of her biggest mistakes.

“What’s my lesson? The lesson is you take it all with a grain of salt,” she said.

High on her list of Senate accomplishments is gun control legislation – especially the assault weapons ban in 1994. It eventually lapsed, and she took the lead trying to revive the ban after the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut.

“It wasn’t to be,” she said, with regret in her voice and on her face.

Even at the time, it was hard to believe that Feinstein was the oldest member of the US Senate – she was 83 when I spoke with her.

When I told her people would be shocked to learn this, she smiled with an uncharacteristic sheepish grin.

“Don’t rub it in,” she joked. “It’s what I’m meant to do, as long as the old bean holds up,” she said, putting her finger on her temple.

Though she is a proud native of one of the most famously liberal cities in the country, Feinstein has earned a reputation over the years in the Senate as someone eager to work across the aisle with Republicans.

“You have to remember how I became mayor. I became mayor after being defeated twice as a product of assassination, of the mayor being killed and the first openly gay public official in America being killed by a friend and colleague of mine. So I saw firsthand when a city becomes divided, I saw and watched while squad cars (were) being blown up in a riot,” she said.

“I truly believe that there is a center in the political spectrum that is the best place to run something when you have a very diverse community. America is diverse; we are not all one people. We are many different colors, religions, backgrounds, education levels, all of it.”

Her advice to women who want to be the next Dianne Feinstein?

“You mean there’s some?” she smiled and said without missing a beat.

“Run, but prepare yourself. So many times, and I’ve seen it happen in the Senate elections, talented young women go for the top first. You can’t do that. Start young and, you know, with a commission or committee or special effort. Earn your spurs.”

“You don’t drop out, you take defeat after defeat after defeat, but you keep going.”

Read the full article here