The calculus that venture capitalists make in the defense sector is harsher than in other businesses. But few in government and too few in the private sector understand how it really works.

Jake Chapman, managing director of San Francisco Bay area firm Marque Ventures, has been teaching “VC 101” to Pentagon program managers, contracting officers and warfighters at the behest the Department of Defense.

Formed out of a group with startup and financial management acumen that DoD tasked with trying to save the ill-fated Army Venture Capital Corporation, Marque Ventures is solely focused on the defense sector and is currently building a new $100 million venture fund to follow its previous investment pools.

“Part of my presentation to [DoD managers] is the venture math because I want them to understand where VCs are coming from,” Chapman says. “When they ask a VC to invest in a business and are surprised when that VC doesn’t invest, I explain the reasons why.”

Understanding the incentives that VCs respond to and the pressures that they are under by grasping the math they use can help both company founders and those in government attempting to move new companies with new ideas forward.

The reality is that when VCs deploy their funds to seed a group of fledgling defense companies with promising business cases, they’re betting on just a handful to generate all the returns. Chapman breaks down VC 101 as follows.

When VCs are raising their venture funds, LPs (Limited Partners, i.e. fund investors who provide its capital) want to know what sort of returns they’re targeting. Most VCs are targeting value of three to five-times revenue. But few hit that ambitious target.

“How do VCs actually get to 3x or 5x? It’s not by investing in a lot of businesses that return 5X,” Chapman explains.

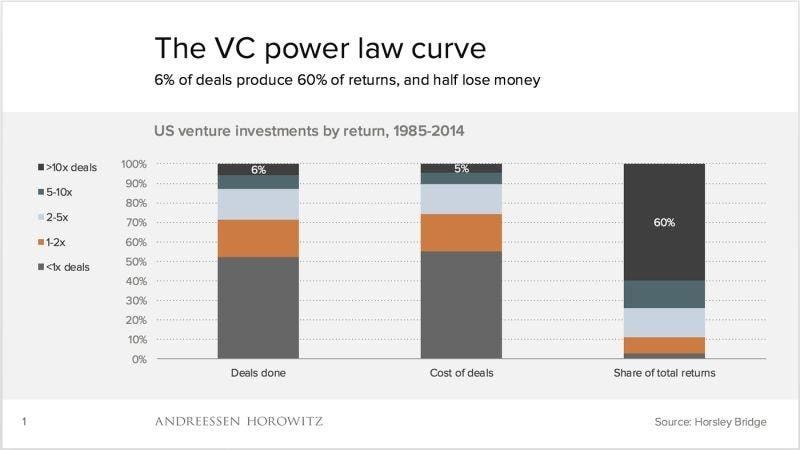

Venture Capital is a “power law” business. In other words a business of successful outliers. The general rule of thumb is that one-third of a VC firm’s portfolio will go to zero, one-third will break even or lose a little, and one-third will generate all the returns.

The distribution is actually starker than that Chapman adds. Six percent of venture investments generate 60 percent of all venture returns. This has a number of implications for VC firm strategy.

“Take a $100 million fund that is targeting a 5X return to LPs, i.e. $500 million,” Chapman posits. “First, the firm quite possibly won’t be investing $100 million. They have fees and expenses for 10-15 years that come off the top. Rather, the firm might invest $80 million. Thus, hitting 5X to LPs requires more like 6.25X of capital invested.”

If one-third of the fund’s investments need to carry the whole portfolio (as per the power law rule of thumb), approximately $26.4 million of the invested capital needs to generate $500 million in returns, or an 18.9X return on investment, Chapman observes.

“It’s really the top 6 percent of the portfolio that needs to carry the fund’s returns. So, we’re relying on $5 million of the original $100 million to generate $500 million in total returns to LPs, or a 100X ROI.”

That reliance on a few startup outliers to generate a fund’s returns explains the frustration faced by founders – and DoD organizations with interest in their potential products or services – in obtaining the capital needed to propel them to market. The problem is more acute in the defense space where VCs need to seek even higher returns.

“There are a lot of founders trying to raise venture capital who keep hearing ‘no’. The reason isn’t that their business isn’t good,” Chapman says. “The reason is that their business is not a potential 50X or 100X. They don’t understand why their business has to be a 50X when most venture funds, especially the large ones, are only returning 2X-3X to their LPs.”

“A 5X investment really doesn’t move the needle for a fund when more than half of its investments are going to go to zero. It’s not intuitive unless you’ve been in the venture fund business for a while,” Chapman acknowledges.

The chief reason that venture math is harder to crunch in the defense industry is the reality of exits (successful sales of VC equity stakes) therein.

VCs typically get their return on investments when the startups they’ve staked are acquired by or merge with existing primes or large to midsize defense suppliers. Initial public offerings (IPOs) of red-hot startups are another path to exit but they are extremely rare.

“M&A [mergers and acquisitions] is where you get your triples and your small homeruns as a VC,” Chapman explains. “In most enterprise-fast businesses [software for example] you can get a 10X or 15X exit on an M&A event. In defense that’s rare. Normally it’s a 1X or 2x.”

The defense primes (Lockheed Martin

LMT

NOC

Even if a defense startup is initially valued by VCs at 10X, a prime isn’t going to pay more than its own value, i.e. 1X to 2X, for it. If they pay more for a startup than the multiple they’re valued at, they get punished by Wall Street, Chapman says.

“Traditionally, that has limited the exit opportunities for defense startups [and VCs].”

Hence the higher rate of return (50X, 100X) that VCs look for in defense startups and the frustration that founders often experience when trying to raise early-round funding.

But potential returns to startups are looking up in the defense space, Chapman asserts. He attributes this to the defense tech startups founded five to ten years ago that are now starting to scale, firms like Anduril and Shield AI which have not only gained market-share but are now becoming acquisitive themselves.

“They’re willing to pay traditional tech industry multiples when they acquire companies. One of the best enduring legacies of companies like Anduril is that they’ve created this exit market for compelling defense tech companies. That creates a pull. It brings more people into the space.”

The “Valley of Death” discussion that so permeates the defense sector currently is balanced by the fact that successful startups which land government contracts have revenue streams that fluctuate less than their private sector counterparts. It’s a reality better recognized in what looks like a high-inflation economy on the edge of recession (or already in it many argue) these days. That can translate to higher valuations, attracting more VCs to defense.

“Defense is counter-cyclical,” Chapman notes. The impact of artificial intelligence on the sector may also accelerate productivity in ways that draw capital more aggressively than in the recent past.

Breaking down the calculus that VCs use for DoD managers and founders may seem dissuasive but it may also lead to identifying better prepared startups for inclusion in fund portfolios faster.

“Once you’ve done this for five or 10 years, you can look at a founder pitching their business and say, ‘I’ve seen that before. Didn’t work last time. It’s not going to work this time,” Chapman says. “But you need to maintain an open mind. I don’t know of anyone else who does this sort of education for the DoD, focused on how venture works.”

It’s a worthy focus. Inside the military, the Pentagon or in the small meeting rooms of startups, more of us need to learn the math.

Read the full article here