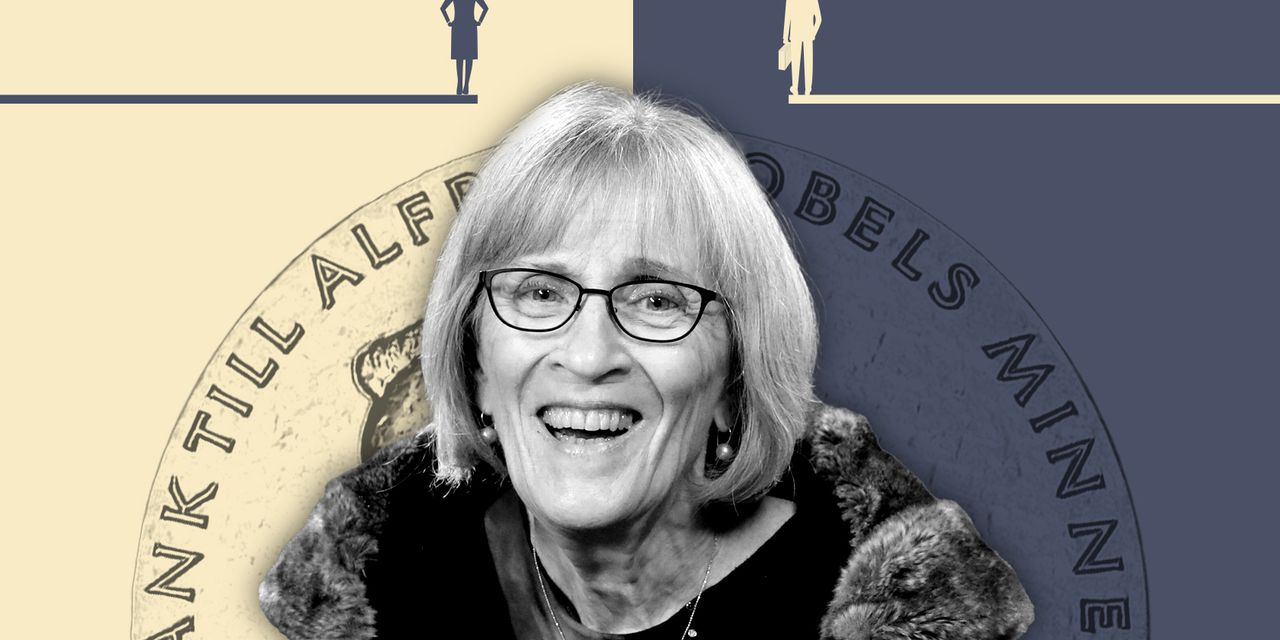

Economists are heralding their colleague Claudia Goldin’s Nobel Prize win, but everyday women — and men — have plenty of reasons to celebrate the historian of women in the workplace.

Goldin, a Harvard University economics professor, was the first solo woman to win the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences and the third woman to win the honor in its 55-year history. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awards the prize, said Goldin had “uncovered key drivers of gender differences in the labour market.”

But economists told MarketWatch that Goldin’s impact reaches far beyond academia, and encompasses more than women’s working lives. Her research, they said, has led to a better understanding of the forces that help women advance in their careers or hold them back.

“We see ripples of her impact through lots of different fields across labor, economics, across education nationally,” said Brian Albrecht, chief economist at the International Center of Law and Economics, a nonprofit and nonpartisan global research and policy think tank based in Portland, Ore.

One of the first rigorous documenters of women in the workforce

Goldin has been a “trailblazer” and “originator” in the study of women in the workforce, economists said. Her body of research spans more than 40 years and documents how factors such as family obligations and discrimination have affected the working lives — and, notably, the pay — of women in the U.S. since the 19th century.

Her more notable findings have included uncovering the link between women’s access to birth-control pills and their expanded career and educational choices. More women entered fields such as economics, law and medicine after oral contraceptives became widely available in the late 1960s, Goldin and her co-author Lawrence Katz found.

Goldin’s work has also documented how gender-related household obligations such as motherhood and caregiving impact women’s career advancement and wages, and help fuel the persistent pay gap between men and women. On average, women in the U.S. currently earn about 82% of what men do, according to the Pew Research Center.

“If it weren’t for Claudia, we (women) would not know our economic roots, where we came from, and where we are going,” Misty Heggeness, a professor of public affairs and economics at the University of Kansas and author of the forthcoming “Swiftynomics: Women in Today’s Economy,” told MarketWatch in an email.

“She has done for the field of gender and the economy what the Beatles did for pop music,” Heggeness said. “And her influence isn’t only felt among women.”

Before Goldin’s time, male labor economists usually excluded women in their analysis of the labor market, because women’s choices were “too complicated” to be put into economic models, she added. Goldin was one of the first to include women, and took the time to “disentangle the trends and the behaviors of women,” Heggeness said.

Though Goldin has focused on women, her research has enabled a more comprehensive view of the labor market, Heggeness said. For example, as men’s educational attainment has slipped and they’ve lost manufacturing jobs over the past few decades, Goldin’s research on women has helped illustrate the broader context of these changes. As men pick up more domestic tasks at home, their median wages and labor-force participation could go down a bit, Heggeness noted.

“You see more stay-at-home dads today than you did three decades ago,” she said. “We wouldn’t be able to really understand or tell that whole story if we didn’t also know what was kind of simultaneously going on with women.”

No paternity leave ‘without maternity leave coming first’

The Nobel winner’s work has also paved the way for new conversations about more-flexible work schedules, a topic that’s driven conversations about work since the pandemic began.

In Goldin’s research, she pointed to the lack of flexibility in working hours as part of the reason behind the gender wage gap. Many high-paying jobs have demanding schedules that include weekend and evening hours, but many women would not be able to take those roles because of family commitments, Goldin pointed out in a 2021 book.

Over the course of the pandemic, many workplaces have transitioned to a hybrid setup that offers remote work and flexible working hours. The biggest beneficiary has been working women: Labor-force participation for women ages 25 to 54 hit an all-time high in July, at 77.8%, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. A significant number of working parents, including Albrecht, were able to work from home and take care of their family life on the side.

More employers also now offer paid leave for parents after a child is born or adopted — an indirect impact of Goldin and her work, Albrecht said. That benefit helped employers and workers, especially working women, to redraw the line between work and life, he said.

“I don’t see how you get men getting paternity leave without maternity leave coming first,” he added.

A role model for younger women economists

Goldin has been a mentor to many younger women in the world of economics, economists said, including many leading female voices who help the public to understand women and the economy today.

Insights from Goldin’s classes, including how social norms influence women’s labor-market outcomes across occupations, “come up again and again as the keys for understanding the most important labor-market trends today,” said Julia Pollak, chief economist at the online job-searching platform ZipRecruiter. Pollak took two classes with Goldin as an undergraduate student at Harvard.

“For me, it’s especially important that she is a woman studying women in the workforce, pushing back against a perception that a researcher is somehow biased if researching a demographic identity that they are a member of,” Kate Bahn, the director of research at WorkRise, an initiative hosted by the Urban Institute, a center-left think tank, told MarketWatch. “She does respected research on a group that she is a part of.”

Goldin was the first female researcher to be tenured in Harvard’s economics department. Her robust research interests have covered a variety of topics, including slavery in the American South and the Great Depression’s impact on education and technology.

“Every single student she interacts with, she changes the trajectory of their lives,” Natasha Sarin, an associate professor at Yale Law School and Yale School of Management, and a former counselor to Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, said of Goldin. Goldin was an adviser to Sarin for her graduate dissertation. “By illuminating existing societal forces and barriers for women, she’s made it easier for women to surpass exactly those types of barriers.”

Andrew Keshner contributed.

Read the full article here