A student-loan organization may be collecting on debt that should have been discharged in bankruptcy and is pushing back on the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s request to investigate, according to documents recently made public by the consumer watchdog.

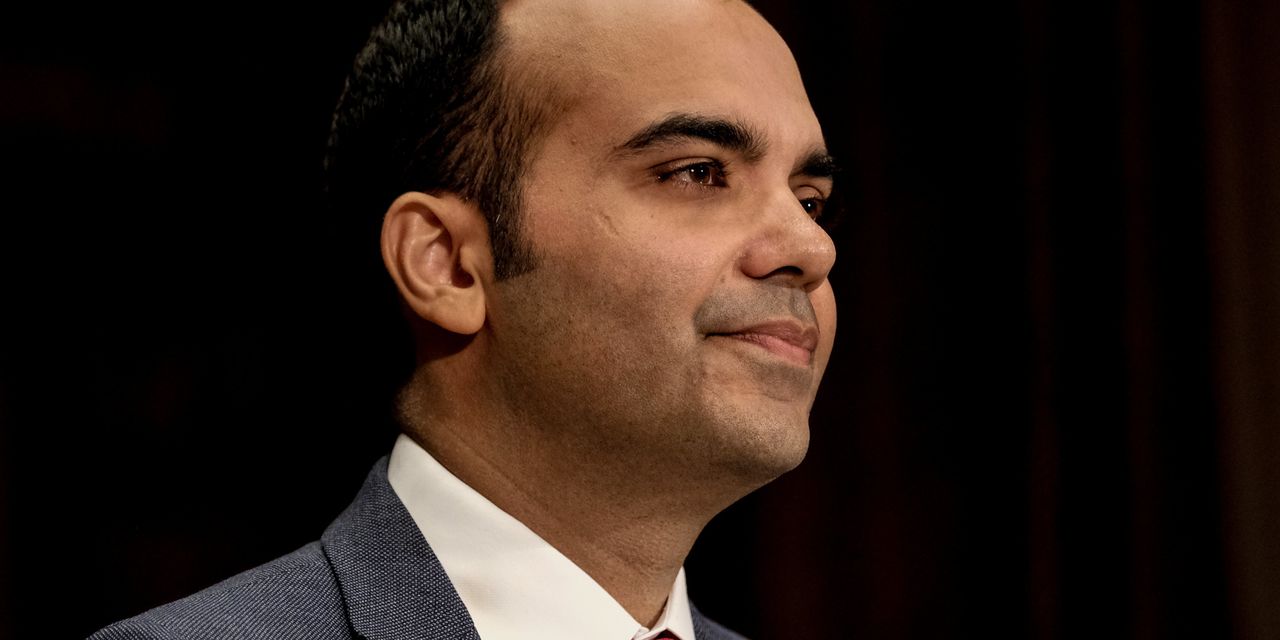

Last month, Rohit Chopra, the CFPB’s director, rejected a request from the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency to set aside an investigative demand from the bureau about PHEAA’s approach to loans it services that may have been discharged in bankruptcy.

That means the CFPB will likely move forward in gathering documents and answers to questions about whether PHEAA attempted to illegally collect on debt that was discharged in bankruptcy. The bureau is also investigating whether the organization failed to set up adequate policies and procedures to figure out if the loans it’s servicing were discharged in bankruptcy.

Chopra’s order is the latest salvo in a battle over certain types of loans used by students that attorneys have argued should be discharged in bankruptcy, but that some companies continued to collect on anyway. Three appellate courts have sided with attorneys and borrowers in this argument and earlier this year, Navient agreed to a deal worth $198 million to settle claims the company illegally collected on discharged debt.

The back-and-forth between PHEAA and the CFPB over whether the bureau can police the firm’s approach to debt belonging to borrowers who went through bankruptcy comes amid broader battles over the CFPB’s authority. This month the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case that will determine whether the bureau’s funding structure is legal. In addition, companies have been pushing back more in the recent past against the watchdog’s efforts to enforce consumer protection laws that may overlap with other regulations or with different agencies’ authority.

As part of its resistance to the CFPB’s investigative demands, PHEAA challenged an element of the agency’s authority, arguing that the bureau can’t enforce the bankruptcy code. In a statement, the company reiterated that position, saying “while PHEAA respects the authority of the CFPB, the Bankruptcy Code does not fall within the federal laws listed by Congress over which the CFPB has oversight.”

“PHEAA strives to conduct all our student loan servicing activities in full compliance with all laws, rules, and regulations,” the statement reads. “We disagree with any assertion that PHEAA’s handling of bankruptcy matters has been inconsistent with the Bankruptcy Code or the orders of the Bankruptcy Courts.”

In Chopra’s order, the director argued that in seeking the documents the agency is investigating potential violations of the Consumer Financial Protection Act as well as whether PHEAA is engaged in unfair and deceptive practices. Those are both issues that fall within the bureau’s jurisdiction, he wrote.

Sending a signal to other student loan servicers

The “CFPB is saying ‘look this might be happening, we want to figure out if this is happening at this institution,’” said Alexandra Sickler, a professor at the University of North Dakota’s School of Law. “It certainly signals to other student-loan servicers that this is on the CFPB radar screen.”

The CFPB is on firm legal ground in arguing that it can investigate whether debt discharged in bankruptcy is being collected illegally, said Sickler, who has studied the relationship between the bankruptcy code and the enforcement of consumer financial protection law. While bankruptcy courts decide if a debt is dischargeable, once they make that decision, other authorities can determine if an entity’s approach to collecting on the discharged debt is violating other laws, Sickler said.

“It’s well-settled that not just bankruptcy courts can police the discharge,” she said.

The CFPB could expand this thinking even further, said Matthew Bruckner, an associate professor at Howard University’s School of Law. For example, the bureau could look to police whether debt collectors or other entities are going after consumers for debt that should be non-collectable because it’s outside the statute of limitations.

“The bureau is effectively asserting, and I agree, that they’re not actually doing all that much,” he said. “Arguably they should do more of this. Not just the student loan context, but in all sorts of debt collection contexts.”

The battle over whether servicers and lenders are illegally collecting on debt that should be discharged in bankruptcy has been brewing for years. Student loans are notoriously difficult to get rid of in bankruptcy because they qualify for special treatment under the bankruptcy code. But in order to be very difficult to discharge, the loans have to meet certain criteria.

The debt needs to be from the government, a nonprofit, or a private lender to cover qualified educational expenses. Essentially, student loans that are difficult to discharge in bankruptcy are those that borrowers take out for up to the cost of attendance at an accredited school. In addition, funds that students receive as a scholarship or stipend and need to be repaid are also difficult to discharge through bankruptcy.

Several years ago, an attorney, Austin Smith, started arguing that in some cases, the money students borrowed while they were in school was more like traditional consumer debt and therefore didn’t need to meet a uniquely high bar to be discharged in bankruptcy. These loans were made to students in excess of a school’s cost of attendance or for services, like a bar exam study course, offered by non-accredited institutions.

Judges started to agree. So far, three appellate courts have said servicers and lenders shouldn’t be collecting on these types of loans if borrowers have gone through bankruptcy. Earlier this year, the CFPB weighed in too, ordering firms that collected discharged debt to give consumers their money back.

The CFPB’s demand for documents from PHEAA is part of its efforts to monitor firms’ approach to debt made to students that the bureau argues was discharged in bankruptcy.

“I would not assume because the CFPB has adopted this view that the industry would immediately move to respond by auditing its books, returning money that it’s stolen from borrowers,” said Mike Pierce, the executive director of the Student Borrower Protection Center, an advocacy group. “It actually feels like the CFPB is doing the hard work of inventorying who has had money stolen from them by unscrupulous” student loan firms, he said.

Size of portfolio at issue is unclear

It’s hard to know the size of PHEAA’s portfolio of loans that are arguably eligible for discharge in bankruptcy. The CFPB declined to comment beyond the documents made public last month. But PHEAA is the primary servicer of a cohort of loans made during the run up to the financial crisis to students at for-profit colleges beyond the cost of attendance, Pierce said.

“These are the loans that are the most likely to be dischargeable in bankruptcy,” he said.

To Pierce, the fact that PHEAA is getting in the way of borrowers’ ability to have their debt discharged is one sign of the dysfunctionality of the student loan system. “PHEAA is a zombie,” he said.

The organization was created by the Pennsylvania state legislature in the 1960s. It provided loans to students in the state and was guaranteed loans made by private lenders as part of the government’s bank-based lending program. When the government switched to making loans directly to students in 2010, PHEAA continued to participate in the student-loan program as a servicer.

The organization announced it would leave the federal program in 2021 amid mounting criticism over the way it managed the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program, which allows public servants who have paid on their student loans for at least 10 years to have the remainder discharged. For years, borrowers who met the spirit of the law struggled to access the relief.

Advocates like Pierce have derided the way that organizations like PHEAA have remained part of the student-loan system, even after lawmakers got rid of the bank-based lending program in an effort to cut down on the middlemen involved.

The six Republican-led states who successfully challenged the Biden administration’s mass loan forgiveness plan centered their argument around the revenue the debt relief plan could cost the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority, or MOHELA. That organization began as part of the bank-based loan program, but continued on as a servicer once the government started exclusively making loans directly to borrowers.

“Its purpose was to help people get federal student loans back when banks made them,” Pierce said of PHEAA. Now, more than a decade removed from the end of the bank-based loan program, “the company is just bouncing around through the private sector looking for business opportunities helping it exist.”

Read the full article here