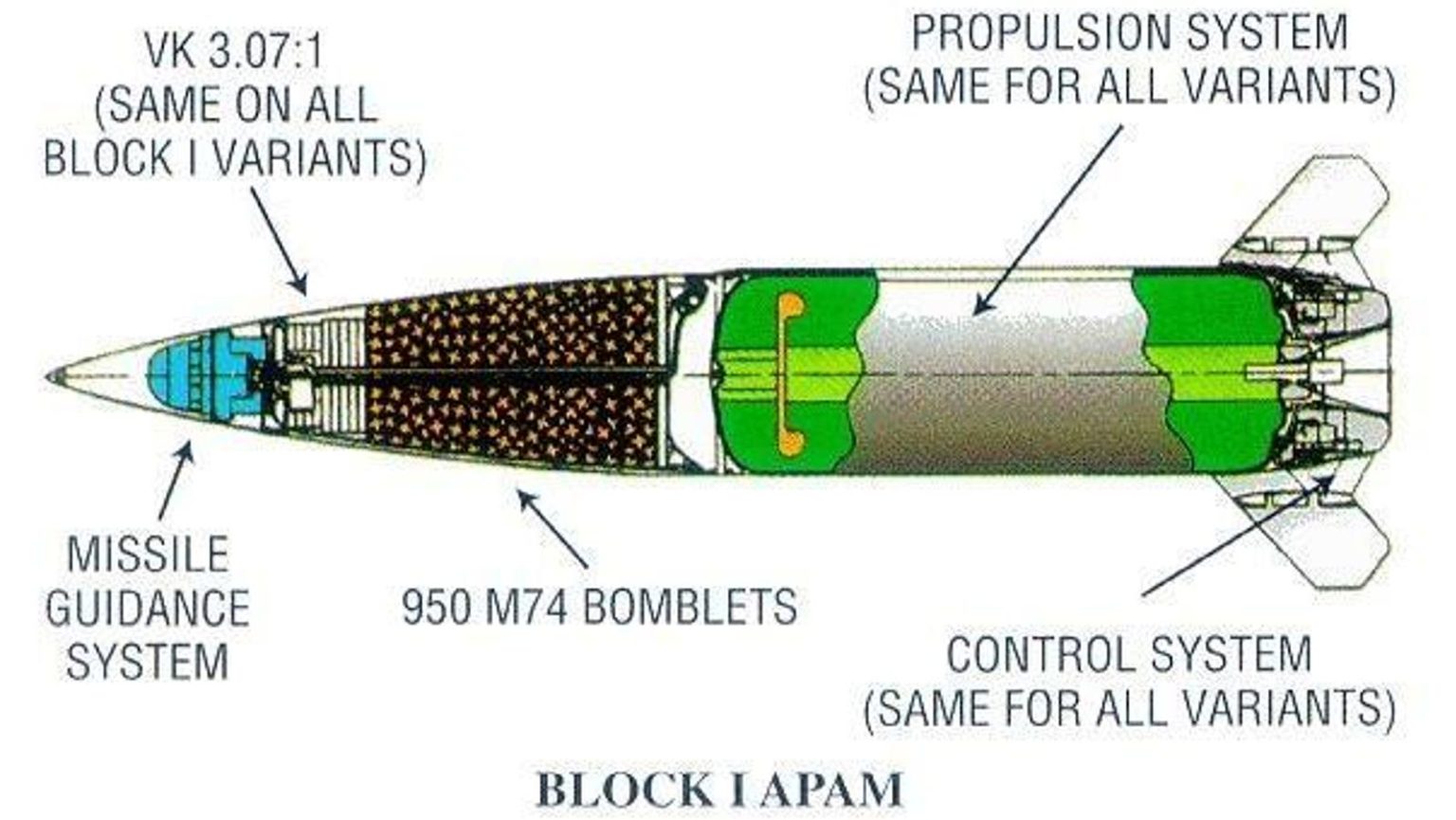

The U.S. Army’s M39 Army Tactical Missile System is a two-ton, 13-foot ballistic missile with a solid rocket motor and a warhead containing 950 grenade-size submunitions. Fired by a tracked or wheeled launcher, the 1990s-vintage missile ranges as far as 100 miles under inertial guidance.

For 33 years, the M39 has been one of the most powerful deep-strike munitions in the U.S. arsenal. And now it’s one of the most powerful deep-strike munitions in the Ukrainian arsenal.

The Ukrainian army last night lobbed three of the missiles at the Russian airfield in Berdyansk, in Russian-occupied southern Ukraine. The attack came shortly after the administration of U.S. president Joe Biden quietly shipped a consignment of M39s to Ukraine.

A video depicts the airfield in flames; the Ukrainian defense ministry claims it destroyed nine helicopters between the Berdyansk strike and a simultaneous raid on Russian forces in Luhansk Oblast, farther to the east. “ATACMS have proven themselves,” Ukrainian president Volodymr Zelensky said.

The M39’s arrival, 21 months into Russia’s wider war on Ukraine, signals a major shift in the firepower balance as the war’s third winter looms. “We believe this will provide a significant boost to Ukraine’s battlefield capabilities,” a U.S. National Security Council spokesperson said.

“It’s not a wunderwaffe,” analyst Brynn Tannehill wrote about ATACMS back in September. “It will not singlehandedly win the war. But oh wow, will it complicate things for the Russians. ATACMS can hit everywhere in occupied Ukraine (including Crimea) with minimal warning.”

The M39 with its nearly 1,000 submunitions is an area weapon. It doesn’t punch through concrete and steel the way, say, a British-made Storm Shadow cruise missile does. No, it sprinkles its submunitions across potentially thousands of square yards.

It’s not for no reason that, when it tested the M39, the U.S. Army aimed the missile at a mock airfield where the service parked old helicopters and trucks. Footage of the test depicts submunitions tearing into the vehicles.

Airfields, command posts, supply depots, vehicle repair yards, troop staging areas—all are in danger. “ATACMS gives Ukraine the ability to hold most Russian high-value assets at risk as long as they are in Ukraine,” Tannehill wrote.

Russian air-defenses won’t save them. The Russians’ best S-400 surface-to-air missile batteries can’t reliably intercept the Ukrainians’ subsonic cruise missiles. It’s even harder to shoot down a supersonic ballistic missile.

The Russians could target the tracked M270 and wheeled High-Mobility Artillery Rocket System launchers that fire the M39. But it’s worth noting that, nearly two years into the wider war, Ukraine’s hasn’t lost a single one of its roughly 60 M270s and HIMARS.

To mitigate the M39 threat, the Russians will have to change their behavior. And that’s whole point, Tannehill explained. The missile “creates all sorts of dilemmas and calculations with no good answers.”

For instance, knowing that M39s could strike at any time could compel the Russian air force to pull its surviving Kamov Ka-52 attack helicopters out of Berdyansk and other bases in occupied Ukraine and instead operate them from bases outside ATACMS range, in Russia proper.

“Sure, the Ka-52s can fly to the front from inside of Russian territory, but their loiter time is greatly reduced, because it adds an additional 50 nautical miles distance they have to fly to get to the front if they’re operating out of Taganrog” in Russia.

In that way, Ukrainian M39s could suppress Russian air power without actually striking all of Russia’s front-line airfields.

Equally exciting for advocates of a free Ukraine, there’s no shortage of old M39s in American warehouses. The U.S. Army acquired around 1,700 M39s from Lockheed Martin between 1990 and 1997, and fired around 400 in the wars with Iraq.

The Army upgraded some M39s to M57s with GPS guidance, but it’s possible around 700 of the older missiles still are lying around. The oldest of the M39s technically are expired, but a quick inspection should confirm that their motors still are viable and safe.

All that is to say, the United States could supply Ukraine with enough M39s to hold at risk vital Russian installations throughout occupied Ukraine for a year or more. The Russians must radically change the way they fight—or accept profound losses as potentially hundreds of M39s rain down, scattering hundreds of thousands of submunitions.

Read the full article here