When Johnny Marr was only 12 years old, he started his first “job” at a guitar store in Manchester, England. The shop wasn’t allowed to employ him legally, but the owner was amused by the loitering pre-teen’s enthusiasm. While the young musician wasn’t allowed to handle money, he paid his dues moving boxes and polishing guitars. Every Saturday morning, he arrived ready to linger all day.

“I was like this excited little puppy,” Johnny Marr says. “This was heaven for me.”

In his stint helping the guitar shop, The Smiths founder and guitarist first discovered the unique relationship musicians hold with purveyors of instruments. He jokes about the countless times someone would enter to buy a guitar strap, but stay to tell their life’s story—how the brave souls behind the counter were like bartenders, albeit with less patience or compassion.

Over the course of his career, Marr has acquired an astonishing collection of instruments and still romanticizes the feeling of playing a new guitar. From the age of 16, he avoided the faux pas of sampling “Stairway to Heaven.” Instead, he’d start a test-drive by doodling his go-to: “Kid,” by The Pretenders, a song he learned in 1979 and eventually performed as a member of the band after the dissolution of The Smiths in 1987.

“I have to surmise that my life has turned out pretty f***ing crazy,” he says. “I was 24 then. I realized, ‘S***, my life is pretty nuts!’”

In the decades that followed, Marr returned to “Kid,” The Smiths’ “Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others,” and Modest Mouse’s “Dashboard” each time he picked up a new guitar. And just as the songs were consistent, so were his feelings when he entered a shop to play them.

“There’s a feeling of awe that comes over, ” Marr ponders. “I won’t say it’s like church, but it’s definitely not like going into Jack in the Box or a clothes shop. There’s a wonder and a reverence. I haven’t really thought of that. That’s a nice thing to think about.”

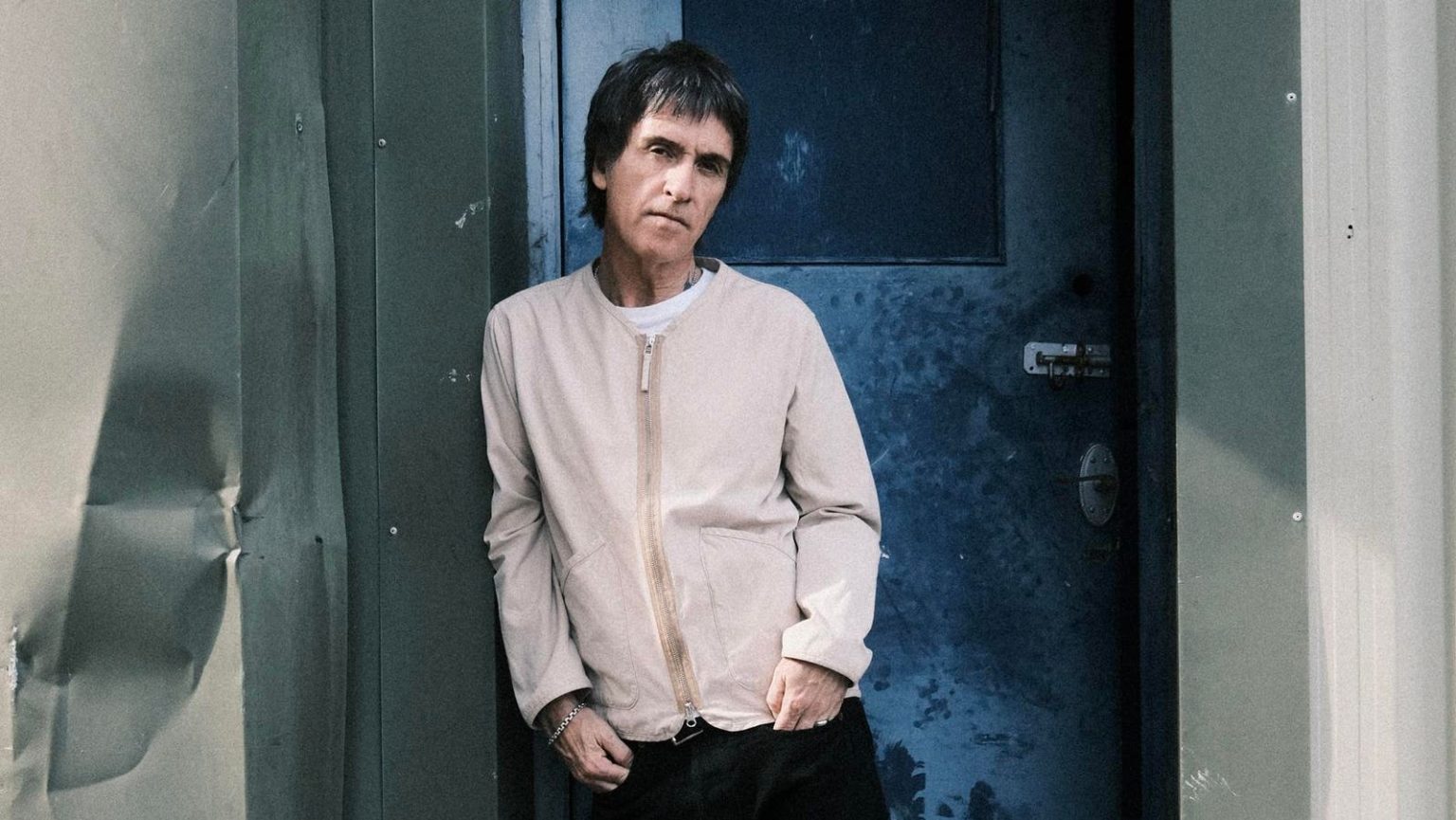

On the brink of 60—Marr’s birthday is on Halloween—he still fights the urge to exhaust guitar salesmen. He doesn’t want to come off like those babbling dorks he witnessed many years ago.

“I try not to be that guy who goes in and starts telling old war stories—unless someone wants to know,” Marr says, cracking a smile. “Hey, listen, I get to do it in a book … I just realized that I’ve just done the mother of that whole thing.”

Sitting in his home studio outside of Manchester, the room is packed with a selection of his 132+ guitars (he stopped keeping count). Steps away, you can see a black 1994 Gibson EDS-1275 Double Neck (12 and 6 string) he used to score the Christopher Nolan film Inception, and a bronze 1961 Silvertone 1415 that once belonged to his hero, Irish songwriter Rory Gallagher. Nearby, he has a storage space for his entire collection, which he assures is guarded by “very large dogs.”

He’s happy to point out the gear surrounding him, which is only a sample of what’s included in his nearly 300-page photographic coffee table book, Marr’s Guitars, out now. The wonderfully curated and intentionally detailed collection is eye candy for music fans of all kinds. Marr, who remembers visiting friends’ homes as a child and browsing through books of automobiles or zen gardens, hopes his book can reach a wide audience.

“I would like for people who would normally have a book of exotic plants or architecture—and wouldn’t even consider having a guitar book—to find this beautiful,” Marr explains.

While the book does have a gorgeous aesthetic—courtesy of photographer Pat Graham—it also translates outside the world of guitars. It wasn’t designed solely for fans, but definitely satisfies any alt-rock nerd’s needs. As Marr explains, the collection is a culmination of his life in music.

Take, for instance, when Marr traveled to Oregon to work with Modest Mouse in 2005. While playing in a Portland attic, he discovered the Fender Jaguar after decades of success using other models.

“I’m not exaggerating when I say that was a life-changing moment,” Marr says. “What’s more is that I knew it at the time. That can sound like big talk, but the facts bear it out. I’m still playing that guitar exclusively on stage.”

Today, he doesn’t even change guitars when he performs. It’s surprising for a man with so many to opt for the “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it” approach, but who can blame him? Just last year, he won an Oscar for his performance on Billie Eilish and Finneas’ James Bond “No Time To Die” theme—along with Hans Zimmer, who wrote the foreword to his book—as well a Grammy, Golden Globe and more. Damn right, he was playing a Jaguar.

“I start sounding a bit mystical and esoteric,” Marr says. “But that’s because I look at all this stuff with significance. I have since I was a kid. I have massively philosophical attachments to some moments. They have come out in the telling of the stories. If I sat at a word processor, they probably wouldn’t. Guitars made me tell those.”

Marr’s Guitars begins with a black 1980 Gibson Les Paul Standard, the first professional guitar he purchased, acquired from a shop called A1 Repairs. Not long after buying it, he traded it in for a cherry red 1977 Gretsch Super Axe, on which he wrote and performed much of The Smiths original music. Forty years later, a friend found the Les Paul and returned it to him. Through the images of Marr’s growing inventory, the book tracks those that have come and gone, the stories behind them and their sentimental value.

“[The collection] has grown around me,” Marr says. “Back then, me and my girlfriend, now wife, had an apartment, and every bit of money I got that I could spend on a guitar, I did. Next thing, I had two, three, then seven. The Smiths records sounded like I was getting even more because there’d be a 12 string acoustic on there, then a cool sounding six string acoustic, then a rockabilly sound would come in. Then I would get a 12 string electric—because I didn’t have one of those! Then the group sound expanded a bit again. Then a Strat with a whammy bar. All the guitars were an inspiration going into my writing. In some ways, what I’m doing today is still the same thing. I’m not just putting ’em behind glass cases!”

While quite technical, what Marr is describing is the evolution of the sound of The Smiths—a pivotal journey within the cultural evolution of British rock—which impacted the global trajectory of music. But don’t worry, the stories in the book aren’t driven by ego.

Each tale is a glimmer, every guitar unraveling personal moments that were inspiring and formative. In totality, it’s a beautiful journey, even if that wasn’t Marr’s initial intention. Originally, his idea was to help curate an abstract, tightly-composed and artsy book that focused on rust, dings and details.

Take, for example, photos of a custom black 1978 Stratocaster, which highlight its excessive accouterments: nine pickups and 18 switches.

Marr explains that he bought the guitar at a Duncaster shop in 1992 with his new friend Noel Gallagher (more on him later).

As Marr and his friends sorted through the gear, he was flooded with even more memories: remembering times he loaned guitars to New Order or Radiohead, or was gifted one by Nile Rodgers.

“It’s actually been a nostalgia trip for me,” Marr explains. “I’m not a particularly nostalgic person. But there’s something about the instruments that brought back a lot of feelings, more than when I wrote my autobiography.”

While the photography book inadvertently opened a floodgates of emotions and anecdotes, it also helped contextualize the style and circumstance surrounding the hardware. Marr’s recollections transport the reader to a different time, where in the seventies and eighties, he was hard-pressed to find a guitar to hold.

“Now every household has a guitar or knows someone who has one,” Marr says, “Back then it was really unusual. I would read stories about Jeff Beck or Marc Bolan (T-Rex), these guys who grew up in the fifties, and it was similar, only in their cases it was with records! They’d be like, ‘Oh, there was a guy who had a Muddy Waters record!’”

As he became obsessed with guitars, he kept tabs on everyone within a 10-mile radius who owned one. He’d often ride a bus or train just to knock on someone’s door unannounced and ask to see it. Was it an imposition? Totally. Did he care? Not really.

In retrospect, Marr acknowledges that his origin stories feel on par with tales of older classic rock icons. He’s cool with that—it’s part of being an older guy. However, he still asserts that his generation’s ideology was kicking back against their predecessors. This carried The Smiths far in a brief period.

Marr’s drive for guitars didn’t stop at front doors—on one occasion, he even dragged a record executive through the snowy streets of New York to buy one. When The Smiths first struck a deal with Sire Records in January 1984, founder Seymour Stein promised he’d present Marr a new guitar as a signing bonus.

“Do you know when it gets really piled high on the sidewalk at the side of the road?” Marr says laughing. “It was that kind of snow. We signed a deal, then I hung around the building. He had business to take care of. I was standing around thinking, ‘He better come through!’ I was worried until I got this guitar in my hands. He wasn’t going to leave my sight.”

Stein made good on his promise. The result of their journey to 48th Street was a cherry red 1960 Gibson ES-355. Lucky for the executive, he immediately saw a return on investment. Moments later, Marr returned to the Iroquois Hotel and wrote one of The Smiths’ biggest hits, “Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now,” followed by “Girl Afraid.” He says the songs flowed out back-to-back, with not so much as a noodle between.

For the following four years, The Smiths released a full-length record annually, unknowingly cementing them as icons of their own sort of rock, driven by Marr’s unique guitar and Steven Patrick Morrissey’s crooning and melancholy vocals. It seems a fruitless endeavor or silly semantic argument to label them rigidly, but their music has and continues to influence a wide swath of genres in alternative music and the mainstream. Before the band dissolved, Marr’s style made a massive impression. But quick success came with quick stress.

“We got a lot of attention almost out of the gate, which is obviously very helpful,” Marr says. “But also it’s something you have to deal with. It’s all very well going, we were critically liked and supported and got interest right from the off. But with that comes a massive amount of scrutiny. I want to say that it isn’t all f***ing roses just because you get attention. But I’d rather have attention than not.”

He continues: “Every record felt like we were really under scrutiny, but that made us really raise our game—which frankly no one had to tell us to do anyway as individuals because we were our own harshest critics. But I was aware that I was getting comments, praise and sometimes criticism for what I was doing on the guitar.”

It didn’t take long for purist fans to analyze Marr’s every move, claiming songs sounded too “rock” (whatever that means)—or crying foul because he played a solid body guitar on stage, as opposed to hollow body guitar (which offers more acoustic tone). He points out how ironic the critique was, considering he played that particular guitar totally clean and without any distortion.

“We were on a mission,” Marr explains. “It’s a mixture of being very confident, which I was, and being put on your mettle by the expectations of the audience and the press. In England, it was a really big deal, and then it became a big deal in the States. It was a perfect storm of conditions that made you push yourself in the writing.”

He cites tracks from The Smiths’ final record, Strangeways, Here We Come, where he left the songs “deliberately empty,” avoiding his widely adored style of layered guitar: “Unhappy Birthday,” “Death at One’s Elbow,” “I Won’t Share You,” and “Paint a Vulgar Picture.” On the contrary, the album’s first song, “A Rush and a Push and the Land is Ours,” included no guitar at all, whereas “Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before,” did include more complex composition.

“I didn’t layer [some of] them because it was braver and cooler not to,” he says. “That was actually more radical than putting loads of guitars on … We were being tested and we were brave enough to step up. All those conditions put you under pressure, but they’re good for you. And we were young to be under that kind of pressure, particularly me. By the time the band split, I was only 23.”

As The Smiths rose in popularity, Marr and Morrissey wrote songs that were distinctly theirs. Marr recorded music that was dynamic yet approachable—the idea of shredding like a metal band, he jokes, topped his list of “what not to do.”

“That distinctive sound, 60 percent of it was the agenda that I had when I formed the band, having made all these tapes in my bedroom with this idea of layering guitars,” Marr explains. “The rest of it was reacting to all of these things that I’ve mentioned, whatever the band needed to be at that particular time. It’s an evolution that you don’t plan. But half of it at least was deliberate.”

When The Smiths broke up and Marr joined The The to write Mind Bomb, the band’s creator, Matt Johnson was coming off his own success with the record Infected. Suddenly, he had one of The Smiths in his band, and the pressure didn’t go away for anyone. It’s safe to say it hasn’t subsided in the decades that followed, either.

There will always be interest in Marr’s debut musicianship and residual estranged relationship with the ever-polarizing Morrissey. As the two both continue to perform as solo acts (Morrissey is on a 40-year anniversary tour now), Marr is grateful and humble about the impression that he’s made throughout his entire career—and those four magical years.

“I was aware that what I was doing was different, but I had no idea of the impact—that has now happened over years and years,” Marr explains. “Obviously it pleases me, but it’s genuinely something I can’t analyze because it’d make me nuts or very, very boring. I try to live up to it. I guess that’s the conclusion of that thought. I just have to live up to it.”

He continues: “Everything I’ve done has always had a certain amount of having to prove yourself. That probably has kept my mind occupied. Sometimes I’ve been able to measure up and some of the times I’ve maybe missed the mark. But I’ll be honest, at the age I’m at now, I feel like I haven’t got anything to prove to anyone except myself—all the time.”

Serendipitously enough, Marr’s book also details a camaraderie with another alienated rock star: Oasis guitarist and songwriter Noel Gallagher. Just as Gallagher is also of Irish heritage and raised in Manchester, he too experienced a lightning strike of success—which ultimately led to a famous estrangement from his brother, vocalist Liam Gallagher. In Marr’s Guitars, you can follow the two’s chance, but rather appropriate, friendship—through the sharing of guitars.

“In all honesty, when I first met Noel, I liked him a lot,” Marr says. “I saw a young kid. I didn’t make too much of a big deal of it at the time, but the fact that his background is quite similar to mine, that Mancunian-Irish thing, I think makes us understand each other quite well. We really clicked. I had no idea, no one had any idea that they were going to be as big as they went on to be. Not even himself—maybe himself—but they hadn’t even made a record! They played maybe four little shows.”

The respect and admiration is mutual. Despite Gallagher’s notoriously blunt and snarky public persona, he speaks of Marr, and the guitars he’s received from him, with a childlike wonder and glee. When Marr first saw Oasis perform, he decided it would be reasonable to loan Gallagher a guitar as a back-up in case he broke a string or needed to re-tune. He received a Sunburst 1953 Gibson Les Paul Standard, which Marr had acquired from a small band called The Who.

“I couldn’t give him something crappy,” Marr says. “That was my logic. I better give him something he’s going to really buzz off. Oasis could have been never heard of. It could have just been a guy, and I still would’ve given it to him. It turned out so well for everybody. I don’t need those guitars back from Noel. When I saw him playing it, he just looked right. It’s his guitar. And then our careers and lives got so intertwined, and in some ways still are. Now, we play together more than ever on record.”

Gallagher went on to use that guitar to write the Definitely Maybe track “Slide Away,” and it even appears in the band’s video for “Live Forever.”

In a chaotic turn of events, the guitar was damaged in an on stage brawl at an Oasis concert in Newcastle. Gallagher jokes that he wielded it like an ax. Days later, Marr loaned him a different guitar, a black 1978 Gibson Les Paul Custom that was used on the recording of The Smiths’ The Queen is Dead. Gallagher ended up keeping it.

“The fact that years later I ended up playing that guitar on an Oasis record (Heathen Chemistry, 2002) was a nice loop around,” Marr says. “When I was starting out, I had a helping hand from a few kind people. So if you are put in that same position, why not?”

Aside from sharing a hometown and heritage, the parallels between the two seem almost impossible. While Oasis’ run lasted far longer than The Smiths, and consisted of seven albums, the band’s whirlwind success during a few-year stretch in the nineties cannot be overstated. It was met with just as much scrutiny as Marr had received a few years prior. And despite both guitarists having decades of impressive musical endeavors since, many conversations come back to where it all began.

“Noel is interesting in many ways,” Marr explains. “The thing about Noel is that because he’s so unpretentious and genuinely down to earth, people think they know him. And because he’s so outspoken—which a lot of that is because he knows it’s funny, right? But in a way, I’m going to blow his cover a little bit now. But it’s almost like to cover up the fact that he’s really deadly serious about what he does, and that he puts a lot of thought and work into it.”

He continues: “That guy is one of the most dedicated people I’ve ever come across in any line of work. He’s extremely disciplined, much more than people give him credit for. And like a lot of people genuinely who are great, he makes it look like he just rolled out of bed in the morning and went, okay, I just knocked out this song.”

Perhaps that’s why the two get along so well. Over the years, they’ve continued to collaborate on music, including a track on Gallagher’s 2017 record, Who Built The Moon?, entitled, “If Love is the Law.” Marr says he’s never heard a song like it—a western or Ennio Morricone vibe with a classic rock melody and harmonica—truly eccentric music.

Similarly to Marr—who continually reinvented himself with bands like The Pretenders, The The, Electronic, Modest Mouse, The Cribs, and by scoring film, all whilst Morrissey has done his own thing—Gallagher has redefined his own career with Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds as Liam Gallagher continues his own solo journey (he just sold-out a European Definitely Maybe 30-year anniversary tour). Both artists push along as the public speculates, gossips and cries for reunions.

“What I’ve seen, being him for 25 years, he plays it down, but it takes a lot of mental fortitude,” Marr says. “That guy has got a lot of pressure that he’s able to shrug off in a way that I wouldn’t be able to. Even just the way he deals with the public because he’s so recognizable in England.”

“To do what he had to do and steer and be the captain of that [Oasis] ship—people don’t even think about what that must’ve been like. He’s a lot more than meets the eye. But I think people are starting to realize that now as he’s got older, which I’m pleased about because I saw that from day one.”

For all of the ambiguous similarities between The Smiths and Oasis, a patently clear distinction between the two exists in the music and the culture surrounding it. While only seven years passed between The Smiths’ final record and Oasis’ debut, a lot had changed in England. Marr maintains that the ideology and politics of The Smiths were far different than bands in the nineties; and that the group was certainly less “blatantly commercial.” So what was sandwiched between these two moments in time? He says, a major turning point in the zeitgeist.

“You can’t underestimate that in the mid nineties and early aughts, even if you never set foot in a nightclub or wore a smiley t-shirt or took MDMA, you can’t negate the fact that rave happened,” Marr says. “The Verve or Oasis or Blur

BLUR

He continues: “Those bands doubled down. They went, ‘Not only do we like guitars, but we like the Small Faces and the Kinks!’ Oasis were like, ‘We like The Beatles!’ And it became overtly about the symbolism and the aesthetic of what guitar music was about. At the same time, the festival circuit and bands playing to big audiences—that happened because of rave. That was a progression in the live culture. All these big festivals like Glastonbury, Leeds, Reading, where bands had these moments that made them huge—before rave, people didn’t stand in fields in groups of 10,000 or 20,000 or 30,000 people. It was a very interesting time.”

It’s the spirit of these moments: how music can bring people together, that keeps Marr as enamored as ever. Just as Gallagher has been lucky to befriend his own hero in Marr—and swoons over him to others— Marr has been just as lucky to spend time with greats from The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

“My experience with older generation musicians, they’re very much about the stuff they love,” Marr explains. “If you’re hanging with Paul McCartney, you want to know about when he got the idea for ‘Paperback Writer.’ But really, he’s going to get enthusiastic about Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers and Elvis—stuff that turned him on.”

Marr tends to behave in the same way. When talking to younger musicians, he prefers to not talk about himself, but rather, his favorites: Roxy Music, T-Rex, and David Bowie. It helps keep him in check, too. When he’s received accolades from older musicians he admired, he was flattered. He’s tried to pass it along to younger artists over the years, like Nick Zinner from the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, or more recently, Madison Cunningham.

“If you’re an egomaniac, it’ll keep you going for weeks,” Marr says laughing. “But it’s humbling, ‘Oh my s***, man! Pete Townsend (The Who) knows my stuff!’ It’s very encouraging. Unless you’re a dick, you don’t walk around with your nose in the air. Instead you go, ‘Now I’ve got to live up to this, but this is f***ing cool!’”

Now, as Marr’s Guitars hit shelves, he’s also preparing to release a best-of record comprised of solo material, Spirit Power: The Best of Johnny Marr, out November 3. The record also features two new songs, which Marr says rides off the energy of playing arena shows with the likes of Blondie, The Killers, and NGHFB. Next year, he plans to hit the road.

Overall, Marr is content. At 60, perhaps it is all f***ing roses—or the closest it’ll get. He’s excited to share his newest creations with the world. And if the apocalypse were to hit tomorrow—after all these years and a zillion guitars—it’s perfectly clear which one he’d take into a doomsday bunker: his 2018 Fender Signature Jaguar in Comet Sparkle.

“It was designed for me,” Marr says. “I wouldn’t change one thing. For me, it’s perfection. That’s the bar I’ve got to beat if I’m going to beat anything. But at this point in my life, I’ll just be happy to get to the bar. And that’s what I tried to do with the book.”

Follow me on Twitter.

Read the full article here