Early this month, New York-based Consumer Reports announced via press release its all-new Permission Slip app. The app, available now for free on iOS and Android, is billed on its website as “one app to take back control of your data.” The essence of Permission Slip is to give consumers the ability to “take back control of their personal data.”

Its arrival is timely, as October is Cybersecurity Awareness Month.

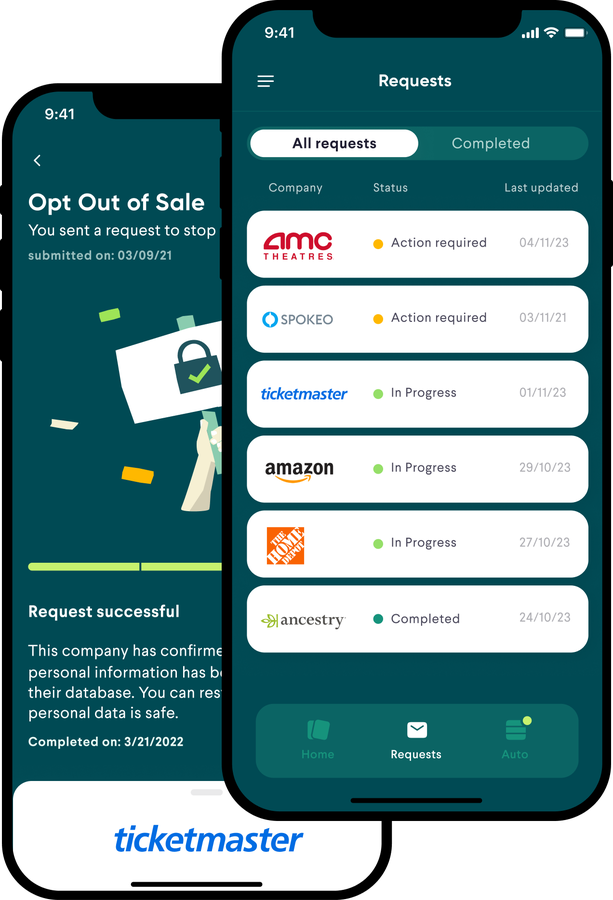

“Permission Slip makes it easy for consumers to manage their personal information. Users can swipe through companies that may have their data, and with a simple tap, send a request for the company to delete their account or stop selling their information,” Consumer Reports wrote in describing the app’s raison d’être in the announcement. “The app currently includes a broad range of industries and companies—from McDonald’s to Applebee’s, AMC Theatres to Ticketmaster, Amazon to Netflix, The Home Depot to Lowe’s, OpenTable to Instacart, and many others. More companies will continue to be added to the app.”

In a recent interview with me conducted over videoconference, Ginny Fahs explained Consumer Reports decided to work on Permission Slip because of “all the work” the agency has historically done on digital rights and privacy. Fahs, who works as director of product R&D of Consumer Reports’ Innovation Lab that conceived and developed Permission Slip, said the agency’s advocates were “very vocal and active and persuasive” in helping shape the country’s first-ever commercial privacy law in California’s Consumer Privacy Act passed by ballot measure in 2018. The legislation piqued Consumer Resports’ curiosity about privacy law, so it conducted a participatory research study during which 500 volunteers were encouraged to go out and tell corporations they were legally barred from selling people’s personal data. According to Fahs, the study found “overwhelmingly, people had really unsatisfying and challenging experiences [in] exercising their rights to privacy.” This frustration stemmed from multiple factors, including figuring out how to opt out, how to ask companies not to sell their information, and more.

“There were all sorts of negative experiences,” Fahs said.

Those experiences were the lightning strike which bore Permission Slip.

Fahs and her team became enamored with a little-known provision in the aforementioned Consumer Privacy Act. It granted the ability to anoint authorized agents to speak on a person’s behalf, kinda like how a sports agent represents players during free agency and other times of negotiation with teams. Consumer Reports had a brainstorm: the agency could build something to help consumers that effectively acts as an agent commensurate with the law. It helped that Consumer Reports has enjoyed longstanding leverage against companies that obviously an individual would lack. Put another way, Consumer Reports leaned on their considerable clout in ways the average Jane or Joe never could.

“It was that insight and that decision to double down that led to [making] Permission Slip,” Fahs said of the choice to forge ahead with the app. “Permission Slip as an easy-to-use app where consumers can see lots of different companies [and] learn about companies data collection practices. They learn about the rights they have with those companies—whether to tell the company to stop selling their information or to delete their information entirely. Then with the tap of a screen, Permission Slip talks to the companies and makes sure those rights get honored on the user’s behalf. We have interfaces that show our users where their requests are in progress and help them understand when requests have been successfully fulfilled by companies.”

Consumer Reports posted a video on Permission Slip to YouTube.

From an accessibility perspective, to appreciate Permission Slip is to appreciate user interface design. To Fahs’ point on people’s frustration with self-advocacy, a cursory glance at most websites reveals businesses purposely design things in such ways that obfuscates and buries any options to limit or prevent data collection. At a functional level, the majority of these controls are written with microscopic fonts and hard-to-click buttons. These shenanigans are inscrutable enough for an able-bodied sheep seeking to protect themselves from the wolves; the hijinks are that much more impactful on a disabled person. Not only is navigating privacy controls a bear in terms of cognitive load, presentation can be tough on a person’s visual and/or motor capabilities. Even the most robust assistive technologies like screen readers often have trouble with the sandboxes companies don’t want you playing in.

By contrast, Permission Slip has been designed, with great intentionality, to be as simple and straightforward as possible. The software uses a card metaphor in the interface to show information about a company and the types of information they wish to vacuum out of users. Text in the app is concise and easy to understand, along with large buttons full of color whose touch targets make it easy to tap. At a foundational level, what Consumer Reports has wrought in Permission Slip stands as the antithesis of the status quo with regards to accessible, functional privacy controls. Fahs told me Permission Slip soft-launched towards the end of the last year, noting the app has undergone a series of changes based on user feedback. At the time of our conversation in the wee days of this month, Fahs said Permission Slip had served 13,000 users and sent over 200,000 privacy requests on behalf of its users.

Following our discussion, Fahs wrote a blog post in which she celebrated a “major milestone” for Permission Slip, saying the app has “initiated over 1 million data rights requests” thus far on behalf of users.

“We now have visibility at much more scale about how things are working [and] what’s confusing about the experience, and where we need to focus to make sure this product is as seamless as we want it to be,” Fahs said of continually iterating on Permission Slip. “We believe privacy is a right. It’s not a setting. It’s not a luxury that should be out of reach of people who can’t pay for it. That’s why this is a free solution where we make it as easy as possible to use your right to privacy.”

Fahs agreed with the notion companies purposely obscure privacy protection interfaces for the obvious reason: they want your information. As she said, it’s “very advantageous” for businesses to hoard consumer data because it ultimately fattens their bottom line following sales of it. The data also is ostensibly useful in learning about people’s preferences in order to build better products, but as many in the tech community like to say: in the end, the customer itself truly is the product. It’s easy to see the logic behind obscuring privacy controls; if people took ownage of their destinies, it’d be very bad for business.

“In general, companies tend to make it hard for consumers to use these [privacy] rights,” Fahs said. “That’s why it felt so essential to build a product like this at Consumer Reports, because we’re a nonprofit institution that is fighting for consumers every day. We’ve been a watchdog for consumers for 85 years [and] our incentive structure and motivations as a mission-oriented nonprofit is to put the consumer first and make sure that consumers get to use all of the rights available to them. That’s why it felt so aligned and important to invest in Permission Slip at Consumer Reports. Companies that are venture-backed or that are more like ‘we need to prove new profits quarter-over-quarter’ don’t have the same incentives to solve this problem in a consumer-first way.”

Alluding to accessibility and disability, Fahs said the right to privacy online affects everyone. She added people are prone to it based on various risk factors and other vulnerabilities, noting many marginalized and underrepresented groups (cf. the disability community) are especially sensitive to guarding against unwanted advances by companies in collecting persona data. “I’ve noticed doing this work that different communities prioritize privacy for really different reasons, Fahs said. “It’s important across lots of different communities [and] underrepresented people; [they] deserve the right to privacy to make sure that they have some control over what companies and government and other institutions know about them. [Permission Slip] is built for everyone. The goal is to make privacy rights accessible to everybody. I do think the issue takes on a different flavor for different communities.”

When asked about Permission Slip’s future, Fahs told me the roadmap includes a heads-down approach to making sure the app works with as many companies as possible. Consumer Reports is looking into expanding the list, with Fahs candidly telling me her personal wish is for Permission Slip to “begin to chip away at some of the learned helplessness that a lot of us have internalized around privacy,” while adding the data industrial complex is s vast economy. Permission Slip exists to simplify and streamline it for all people, from all walks of life.

In short, Consumer Reports wants to help folks take back what’s theirs.

“For the average person, it can sometimes feel insurmountable—the idea we might be able to have meaningful control over our data,” Fahs said. “Tools like Permission Slip go a long way in helping people begin to have that agency and control over what companies know about us. I hope we can begin to change the narrative around privacy and what’s possible.”

Read the full article here