In April I wrote an article titled Staying The Course in which the balance was made up after a tumultuous 2022. Moreover, the strength of the balance sheet was highlighted to illustrate the flexibility management has to execute the plans for its energy transition. This article will further explore the potential effects of European climate legislation on the company while also describing the silver lining.

In the referenced article, a further point of attention was the muted outlook BASF SE (OTCQX:BASFY), (OTCQX:BFFAF) presented, which is currently turning into reality. As a result, the stock price recently reached levels which have not been seen since 2009. The valuation suffers from a slow macroeconomic environment on top of which European legislation adds to the pressure.

Markets slowing

Up till now 2023 has been a slow year for chemical producers. Slower global macroeconomic activity is affecting earnings while capital expenditures are rising. My recent assessment of Dow and its 3Q23 results confirm this view.

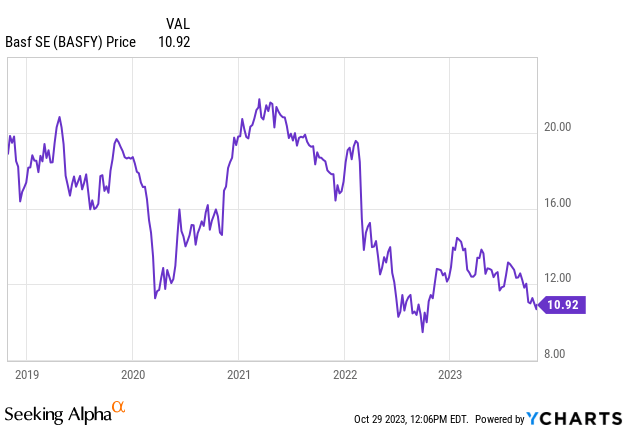

As for BASF, the stock is now trading lower than it did at the height of the pandemic, see figure 1.

Figure 1 – BASF (BASFY) stock price over the last 5 years (seekingalpha.com, YCharts)

The current price level was last achieved in 2009 on the back of the Global Financial Crisis. At that time the company was paying a €1.70 dividend whereas currently this is €3.40 per share. Correcting this for the 1:4 ratio of the ADR, the forward yield is 8.5% provided the dividend will be maintained.

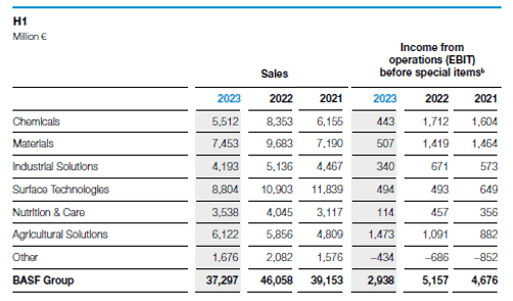

For someone not familiar with the company, the current valuation and yield would conceal it’s actually the largest chemicals producer in the world that has navigated the markets for over 150 years already. There is a reason however for the current valuation which becomes clear if the H1 performance of the past years is compared, see figure 2.

Figure 2 – Comparison of 1H23 and 1H22 financial statements (basf.com, tables by author)

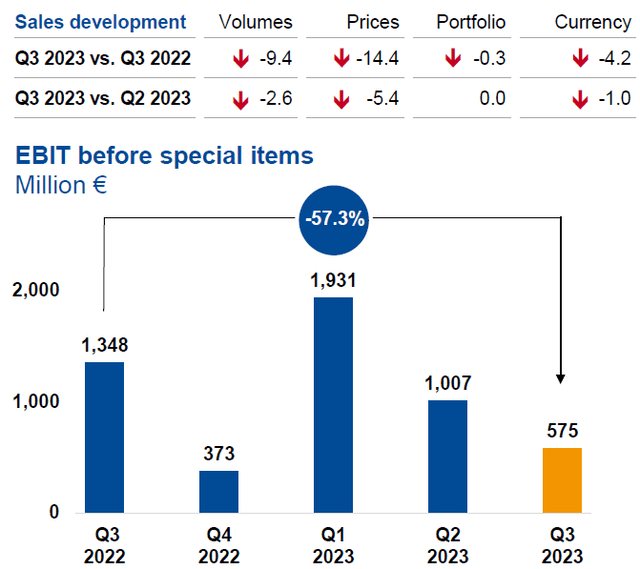

The 2022 numbers came in quite strong given the energy price fluctuations the world experienced last year. But more interesting is the comparison between this year and 2021. Compared to 1H21 sales reduced by 5 percent, but EBIT dropped by 37 percent. What’s more, the contraction seems to be driven by nearly all segments across all geographies in which the company operates. Merely looking at EBIT, the 3Q23 numbers show a continuation of this trend, but it should be noted the comparison base is unfavorable as 2022 turned out to be quite a good year, see figure 3.

Figure 3 – Sales and EBIT development, 3Q23 earnings call presentation (basf.com)

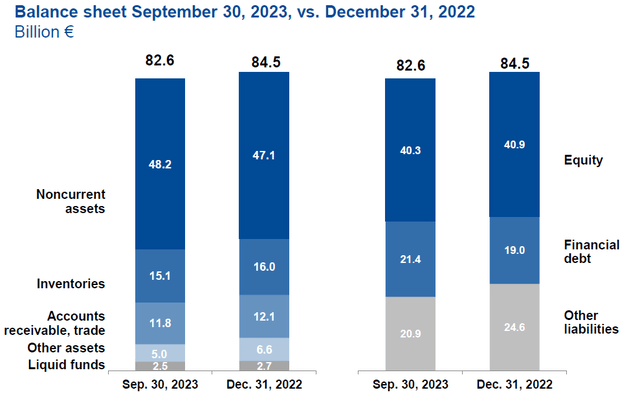

On the upside, year-to-date free cash flow turned positive in the third quarter and changes in the balance sheet do not seem alarming, see figure 4. Moreover, net debt rose €2.5Bn compared to 2022, to a level of €18.9Bn but it is important to see the number stayed level in comparison to the previous quarter. A worry was the company would take on excessive debt to maintain capital expenditures.

While net debt did not increase, the current net debt-to-EBITDA ratio is rather high at a value of 3. Compared this value to 3Q22, the ratio was 2 which is acceptable. If anything, the last quarter of this year will be needed to polish up the numbers as this ratio simply needs to come down.

Figure 4 – Balance sheet development, 3Q23 earnings call presentation (basf.com)

To do so, in the 3Q23 update management indicated to lower the investment for the period 2023-2027 to €24.8Bn, a €4Bn reduction. Acknowledging the extremely uncertain macroeconomic outlook, BASF expects production to stabilize. Therefore, on the income side the worst may be over while management is taking further action to reduce costs.

Emissions Trading System

Apart from slower macroeconomic activity, chemical producers are faced with more uncertainties. The fluctuations in costs for raw materials remain a concern, and in case of European production, further taxation of carbon emissions negatively affects the outlook.

In Europe the so-called Emissions Trading System was enacted in 2005. At the time, in a conversation with a trader at the fuel department of what is now Air France-KLM (AFRAF, AFLYY), the person in question shared it’s dismay stating: ‘Overnight we created an entire industry out of thin air.‘

As it stands, the system is still alive and, with the introduction of the European Green Deal, currently gets another boost as the allocation of free emission rights will be phased out over time and end in 2034.

Although BASF reduced emissions over the years as a result of efficiency and market dynamics, current carbon reduction goals are imposed through legislation. From a high-over, long-term perspective it can therefore be argued Europe will now enter a period of creative destruction. The silver lining of this process however is the relocation of energy sources which will help BASF achieve more control over the cost of energy.

Corporate carbon budget

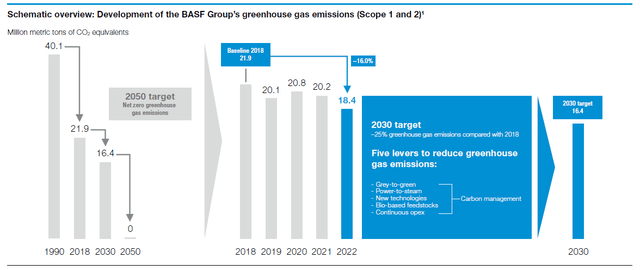

Essentially, carbon emissions are a proxy for the energy use of a certain process. From this point of view, it is only logical that BASF reduced emissions already as it implies fewer costs are incurred. Simultaneously we see the company has been able to increase turnover implying efficiency gains and pricing power. If the long-term performance of BASF is assessed, carbon emissions halved compared to 1990, see figure 5.

Figure 5 – Emission targets (basf.com)

Considering this figure, it must be noted the emissions exclude the sale of energy to third parties. This is another reason to divest the stake in Wintershall DEA as it means BASF does not have to take on the additional burden of carbon emissions from an energy producer.

For 2030, the company set a corporate carbon budget of 16.4 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, which needs to be reduced to net zero by 2050. As free allocation of emissions rights will be fully phased out by 2034, eventually all emissions will be subject to the Emissions Trading System, meaning that an estimate can be made of the corresponding costs.

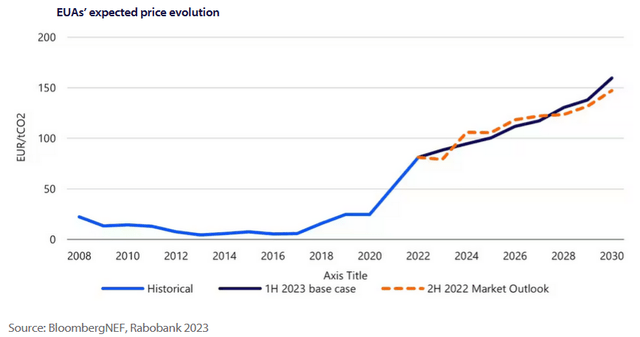

The costs for emission rights, or European Union Allowance [EUA], rapidly rose recently and this development is expected to continue according data compiled by Rabobank, see figure 6. Regarding this estimate it must be noted the displayed period only runs till 2030. As free allowances will be completely absent from 2034 onwards, a further appreciation of allowance prices may be expected after 2030.

Figure 6 – Expected price evolution of EU ETS Allowances (rabobank.com)

Nevertheless, confining the estimate to the data available, assuming all emissions need to be paid for, the carbon bill would amount to €2.5Bn. This estimate is an upper bound as BASF production is not concentrated in Europe. Taking sales as a proxy for emissions, and given that 41 percent of sales were booked in Europe, a better estimate of the ‘carbon added tax’ is €1Bn.

Again it must be stressed this is merely an indication as the actual number depends on a myriad of factors such as exact emission figures, price, changing legislation, management actions and so on.

As the additional €1Bn in costs may seem manageable given BASF is the largest chemicals producers in the world, it does create a disadvantage in terms of costs. EU legislators thought of this as well, which is why the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism [CBAM] has been invented. Essentially this is an import duty producers exporting to the European Union have to pay to avoid ‘carbon leakage’. This term refers to the situation where products are prepared outside the EU after which they are imported to avoid the carbon tax.

Carbon capital leakage

The idea of CBAM, import duties to protect domestic industry, is nothing new. The duties however must be assessed from a global perspective, from research of Rabobank:

“…if extra-EU producers are less carbon intensive, EU producers will be impacted comparatively more by the new carbon policy framework. They will face higher EU ETS-related costs than the CBAM-related levy imposed on their non-EU competitors. These circumstances can allow foreign producers to get more of their foot in the door, leading to increased competition.”

In this light, the development of the state-of-the-art site of BASF in Zhanjiang, can be considered a risk. Hypothetically we may end up in a situation where it is cheaper for BASF to import produce from the state-of-the-art Zhanjiang site to Europe as the carbon pricing renders domestic produce too expensive. Admittedly this seems far-fetched, but looking across the entire value chain, the problem becomes more nuanced.

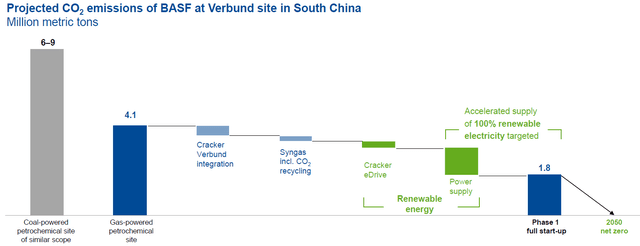

Figure 7 – Zhanjiang site CO2 emissions compared to existing installations, Capital Market Story September 2023 (basf.com)

Figure 7 shows the projected carbon dioxide emissions at the Zhanjiang site compared to a conventional gas-powered site such as Ludwigshafen. The emission reduction is more than 50%, or based on a 150 €/t carbon price, costs are €350 million lower.

The low carbon output of the Zhanjiang site will inevitably end up in other products, cars for example. European manufacturers, sourcing part of their materials in the EU, such as Volkswagen (OTCPK:VWAGY) and Renault SA (OTCPK:RNSDF) already face stiff competition from Tesla and Chinese producers that have aggressively cut prices of electric vehicles. Additional price pressure emanating from a carbon tax will only further deteriorate the position of these manufacturers.

Obviously, this example negates the fact of globalization meaning these European manufacturers can source their lower carbon goods in China as well, but this is not the point. The example is used to illustrate that the European industrial complex becomes more disadvantaged when the governmental bodies impose a carbon tax while capital investments, creating more carbon-efficient production locations, are made outside of the jurisdiction. A situation I refer to as ‘carbon capital leakage’.

As it stands, BASF has reduced capex spending in Europe from more than 50 percent to a current level of 43 percent. In this sense one could argue capital is leaking from the EU to create less carbon-intensive means of production in other jurisdictions from which, hypothetically, the produce is then imported again.

While the effects of the European legislation around carbon cannot yet be overseen, the aforementioned hypothesis of ‘capital leakage’ seems very likely. Again from the 2Q23 conference call:

“…I hear that people are (…) questioning whether it makes sense to produce in Europe. (…) Most chemical companies, like BASF, have global targets. If the conditions in Europe are not good, we will try to decarbonize faster in other regions.

You saw that the China wind farm investment is one element. We get great support in China to do that. Zhanjiang will be a mega, super modern site, totally digitalized, with the lowest carbon footprint. And companies will look into investing more in the U.S. with the IRA where you have a business case for transformation.”

The discussion here evolves around BASF, but it is not hard to imagine the same situation is valid for other companies. In aggregate, the legislation may put EU producers at a disadvantage which will then feed back into the results of BASF as well.

Reciprocity

As it currently stands, CBAM is a one-way street as there is no provision for exports. The mere fact there is no such provision in place means competitiveness of BASF, being a carbon-intensive producer, may be eroded further:

“For products sold by EU producers outside of the EU, the current formulation of CBAM does not (yet) have mechanisms to restore a level carbon playing field. Whether Europe can avoid this so-called carbon leakage (…) depends on whether additional policy measures are implemented to compensate for the loss of cost competitiveness. Such measures might be introduced after the transition period… Without them, carbon-intensive EU producers might (additionally) lose part of their export shares.”

The take-away here is that legislation needs to be amended on the fly as no one has an overview of the ramifications and consequences can only be hypothesized. On top of this, it is not unlikely other economic blocks will reciprocate, and this brings us to the core of the problem. The implementation of the Emission Trading system is spanning decades but has real short-term implications for businesses. In spite of the system being introduced with the best intentions, the lengthy preparations have not led to clarity, quite the opposite. As hypotheses are the only available results, conclusions can’t be drawn as experience is a prerequisite.

The uncertainty regarding the consequences makes it exceptionally hard for management teams to plot the right course of action. A certainty however is that both taxation and bureaucracy will increase, putting an additional burden on companies. In this light, one can understand the growing frustration of CEO Brudermuller as highlighted before and more recently during the 2Q23 results presentation:

“I am worried about competitiveness and the situation the European chemical industry is in. You see on the one hand the volume loss, (…) 20% to 25% of the production volume in Europe has gone. (…). I would make a rough guess that half is actually lost exports, where Europe is simply not competitive enough to sell to the world. The other half is most probably the lack of competitiveness of our customers. So, looking at this and at the same moment looking into the overregulation we get from Brussels (…) it is actually really worrying.“

The silver lining

A question not answered is why EU-based companies will not simply incur the ‘carbon added tax’ and pass the additional costs on to their customers. Maersk for example already announced and priced emission surcharges which will be applicable from January 2024 onward.

Applying a surcharge, however, means a company is still subject to the whims of the market. Vertical integration of the supply chain helps mitigate this. As an example, BASF entered into a strategic merger with Wintershall in 1969 to get access to its own petrochemical elements. As argued before however this investment does not protect BASF sufficiently from fluctuating energy prices. In the last 15 years BASF management has been taken by surprise twice concerning rapidly rising energy costs, right after the Global Financial Crisis and then again last year.

As BASF runs an energy-intensive business, access to cheap energy remains paramount. Therefore the company is reducing its dependency on fossil fuels in favor of renewable energy. For example, both in Europe and China the company is investing in wind farms. The big advantage of sourcing renewable energy is the reduced dependency on external suppliers, Russia comes to mind for example.

In spite of multiple warnings from Washington, the EU learned the hard way that energy dependency makes the continent, and by extension companies, vulnerable. And as experienced last year, this vulnerability translates into excessive costs which affected the performance of BASF. As a result the share buyback program was cancelled and investors now worry about the safety of the dividend.

By moving the energy source from Russia or the Middle East to Europe, the company gains more influence on costs while experiencing less volatility. The silver lining of decarbonization is therefore more control on the cost side of the balance sheet, with the added value of extending the license to operate in a world that requires emissions to reduce. The process will take time, but it does explain why capex investments are favored over surcharges.

The dividend

Given the uncertainties facing BASF, combined with the investment plans, a quick appreciation in price seems unlikely. In spite of a reduction on total capex, my expectation is it will increase further next year, albeit at a lower level, after which it will gradually decline again. As communicated before I expect capex will decrease in 2025 as the first part of the Zhanjiang site will start up. At that moment costs will reduce and income grow as the investment starts to make a yield. As an update on the capex plan will only be given in February 2024 this remains my base case.

Also I expect management to maintain the dividend and accept a deterioration of the balance sheet over the coming two years. This aligns with my previous thesis, especially as management looks through the cycle and keeps focused on the long term.

In the meantime, my bear case is the dividend will be cut. After all, buybacks have been stopped and management subjected dividend payments to the development of the economic environment in the 2Q23 earnings call. In addition, if it turns out chemical production has not stabilized, there is much more downside and further cost cuts will become inevitable. The same holds if wintertime in Europe will be less mild than last year, in which case a repetition of large fluctuations in energy prices is most likely.

As management takes pride in the dividend track record, a cut likely will not be more than 50 percent. This would reduce total dividend expenses from the current €3Bn to €1.5Bn. Given the current €3.40 dividend per share, this would mean it drops to €1.70. Coincidentally this is the amount of dividend that was paid in 2009, the last time the share price traded at a similar level as it does now.

In the event of a cut, the stock price would suffer as well. Still, for a company this size which diligently works towards the future, I would accept a 5 percent yield. This is based on the alternative, Treasuries, which currently have a similar yield. This implies I would consider expanding my position, even after a cut, when the share price (of the ADR) nears a value of US$9.50.

Conclusion

Society is in a new era of industrialization, namely electrification. The displacement of fossil fuels by renewables will eventually increase efficiency as demonstrated by BASF in the emission reductions it already achieved. Whereas these gains have been made through efficiency and market dynamics, current carbon reduction goals are imposed through legislation. From a high-over, long-term perspective it can therefore be argued Europe will now enter a period of creative destruction. The silver lining however is the relocation of energy sources which will help BASF achieve more control over its costs.

Naturally this leads to a period of uncertainty, but the upside can be found in the proposition that humans are most resourceful and innovative in the most dire of times. Or, more colloquially; it takes pressure to create diamonds.

While my personal belief is the current course of action will yield positive results in the long term, inevitably the pressure created will weigh on financial performance over the short term. In spite of identifying adverse times, as a long-term investor I do not view this as a sell signal, but rather as an indication to build up cash with the intention to accumulate. Acknowledging the short-term risks, I am holding my position, but keeping the BASF dividend aside to reinvest at a later date.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here