Factor investing largely came about as a result of the research done in the 1970’s by Eugene Fama and Kenneth French of the University of Chicago, and Dartmouth College, respectively. Their research was an important contribution to the academic field in demonstrating market efficiency. Their 1993 research paper concluded that the variations in stock returns could be explained by a number of risk factors. At first, they proposed a three-factor model of Market (Rf-Rm), Size (SmB), and Value (HmL). Later, they proposed a five-factor model adding profitability (RmW) and investment (CmA).

Ra = Rrf + Bmkt × ( Rmkt – Rrf ) + Bsmb × SMB + Bhml × HML + Brmw × RMW + Bcma × CMA + α

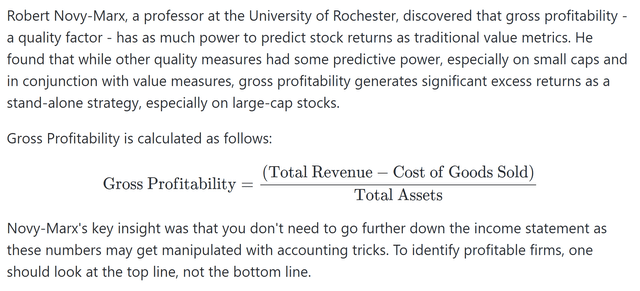

Dr. Robert Novy-Marx of Rochester’s Simon School wrote a paper entitled The Other Side of Value: The Gross profitability Premium. Dr. Novy-Marx discovered there was a premium from robust profitability over weak profitability.

Value Signals

The research is groundbreaking in that it built off of previous research in the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and sought to explain the various dimensions of stock returns. The research was an astounding success and served as the basis for the factor investing movement.

At first factor investing was only available from a financial advisor who partnered with a company that provided access to these funds. Up to this point all of the data in support of factor investing was from a controlled academic setting or done using back testing which did not adequately capture the experience of a real investor holding these factor funds with all their imperfections and costs.

Over time, with the proliferation of factor funds, factor investing began to seem more like a marketing slogan than a real evidence-based strategy. After all, tilting portfolios away from the market factor (Rm-Rf) leads to heavy tracking error and is essentially a form of active management. So, it should be no surprise that the same arguments made against active management (of which there are many) apply to factor investing. As more and more products came on the market targeting these factors, the premiums investors captured from the strategy grew smaller and smaller. Consider the size (SmB) and Value (HmL) factors as two examples from the original three-factor model.

The Small Cap Factor

From 1973-2003, Small cap stocks produced a return of 12.94% vs the market factor’s return of 10.85%, a premium of 2.09%. From 2003-2023, small cap stocks have produced a return of 10.57% vs 10.42% for the market, a premium of just 0.15%. Considering that small cap stocks come with 25.33% increase in the standard deviation of returns, investors were not well compensated by this risk factor. Academics and practitioners began to question the small cap premium, exemplified in a piece written by NYU Professor Aswath Damodaran entitled The Small Cap Premium: Where’s the Beef?

In the piece Professor Damodaran states the following:

“For decades, analysts and investor have bought into the idea of a small cap premium, i.e., that stocks with low market capitalizations can be expected to earn higher returns than stocks with higher market capitalizations. For investors, this has led to the pursuit of small cap stocks and funds for their portfolios, and for analysts, it has translated into the addition of “small cap” premiums of between 3-5% to traditional model-based expected returns, for companies that they classify as small cap. While I understand the origins of the practice, I question the adjustment for three reasons:

- On closer scrutiny, the historical data, which has been used as the basis of the argument, is yielding more ambiguous results and leading us to question the original judgment that there is a small cap premium.

- The forward-looking risk premiums, where we look at the market pricing of stocks to get a measure of what investors are demanding as expected returns, are yielding no premiums for small cap stocks.

- If the justification is intuitive, i.e., that smaller firms are riskier than larger firms, much of that additional risk is either diversifiable, better adjusted for in the expected cash flows (instead of the discount rate) or double counted.

The small cap premium is a testimonial to the power of inertia in corporate finance and valuation, where once a practice becomes established, it becomes difficult to challenge, even if the original reasons for it have long since disappeared.” (emphasis mine)

What this brings to light is that factor returns are a product of the time period in which they took place. The authors of the original study were using fabulous returns from small cap stocks in the 1970’s as the central evidence to their thesis. If there is anything we know in capital markets research, it is that the past is not indicative of future returns. Factor investors are betting on a small cap premium, believing it is their birthright, rather than a theoretical model used to propose an explanation for market returns that may, or may not materialize in real funds, for real investors in the market of the real world.

A post from the CFA Institute commented on the small cap premium in a broader analysis of market cap vs equal weighting for index strategies. The author states succinctly my conclusion for this section.

“Though small-cap performance is enticing over the 90 years since 1926, the excess returns were mostly generated before 1981… Since then, small-cap performance has been rather lackluster…Furthermore, these historical returns are back-tested rather than realized.”

The Value Factor

Goldman Sachs Investment Research

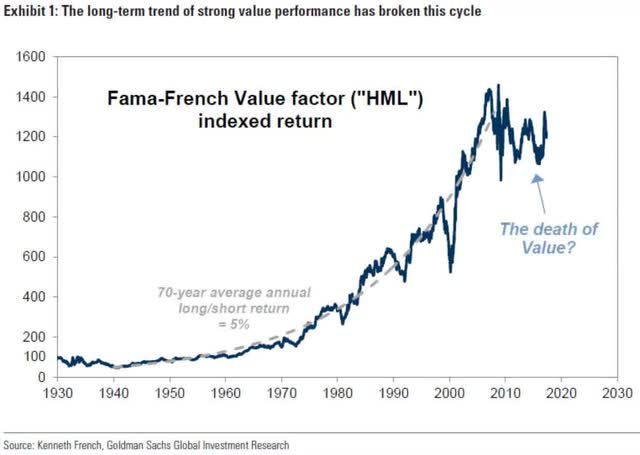

Let’s further our study by looking at the value (HmL) factor. Fama & French saw a significant premium for cheap stocks over expensive stocks. Yet, this again has not proven true in more than 20 years. Will it again materialize, providing investors outstanding returns relative to the market factor? I do not know the future, it very well might, but in the apropos title of Jack Bogles book on the market “Don’t Count on it.” It is important to note, in their analysis they used a long/short strategy to demonstrate a value premium. Most investors however are long only, and thus the research has less applicability than most factor advocates will have you believe.

From 1973-2003 the value premium was robust producing a return of 12.69% to 10.85% for the market. But in the period from 2003-2023, the value factor has drastically underperformed 9.39% to 10.42% for the market. Factor investors are quick to defend their strategy, stating that factors can go in and out of favor and stay that way for decades. But this is the point. Every year that the investor is trying to capture these premiums, they are paying higher fees to do so. When the premiums fail to show up, the value of those added dollars paid out in fees is gone, as is their ability to compound for investors for decades.

Given this fact, it does not seem to be a reasonable decision to decide to tilt one’s portfolio towards factors that could, by factor advocates own admission, be out of favor the entire time you are investing.

An analysis of value investing, over time, provides multiple reasons for why value under performs. The author describes the periods of value out performance as a period where momentum crashes. This would suggest a momentary period of value out performance. ” The idea of an intelligent investor that can buy discounted value and beat the market is connected to periods of momentum crashes. Without the momentum horse, Value has a hard time finishing the outperformance race.”

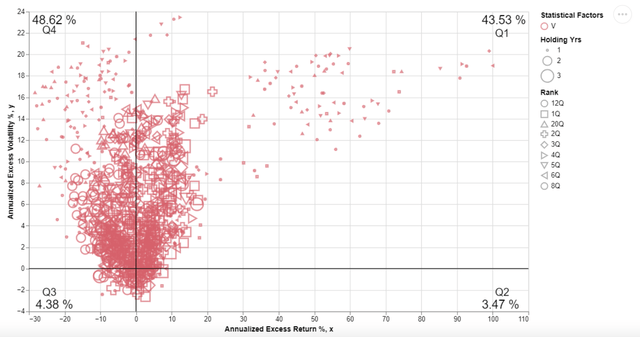

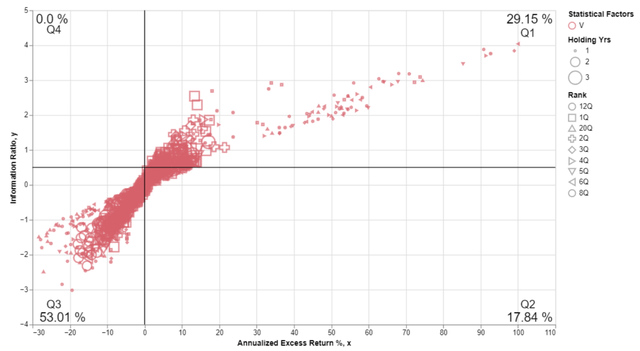

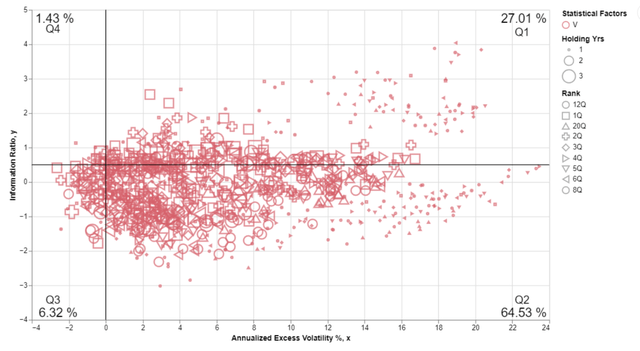

The author further provides a statistical analysis of ten reasons why value cannot outperform growth over time. His analysis shows that value provides excess volatility and negative alpha.

There are many quantitative reasons to explain the probabilistic drag on Value, if we look at it statistically rather than fundamentally. Statistical Value can be defined as relative losers with a certain look-back period.

First; tactical timing looks exciting when it becomes a popular cult but it is hard to implement.

Second; Value is an active investing style, which will always have more risk than naive factor allocation, which is more passive.

Third; Regression of Value from its discounted state is not a strategy, it is extrapolation.

Fourth; negative fat tails of statistical value can be as prominent as positive tails. And when companies get stuck in the Value trap, they drag the overall performance of the portfolio.

Fifth; Value returns have on average higher excess volatility compared to Growth returns. This might seem counterintuitive, but the base effect could contribute significantly to statistical volatility.

Sixth; Lower Kurtosis isn’t enough for a Value strategy to deliver out performance.

Seventh; Fundamental screening is not enough to give a positive skew to a Value strategy.

Eight; Over a long period, fundamental metrics like PE ratios may have shown a negative regression slope, but such behavioral patterns don’t lend themselves to systematic out performance.

Ninth; the level of dispersion in a Value group of stocks is always going to be higher than Growth because, greed is a more converging phenomenon, compared to lackluster Value.

Tenth; It’s an impossibility to predict how low will a Value stock take to become a Growth stock.

Value portfolio built from bottom quintile performers of the S&P500 deliver excess returns at a higher excess volatility (2016-2022) (LinkedIn) Value portfolio built from bottom quintile performers of the S&P 500 has negatively skewed Information ratio and excess returns (2016-2022) (LinkedIn) Value portfolio built from bottom quintile performers from the S&P 500 has more than 70% of data points under 0.5 Information Ratio and 64% data showing positive excess volatility from 2016-2022 (LinkedIn)

The Cost of Factor Investing

This brings us to the final problem with factor investing…the fees.

Up until recently, factor investing could only be achieved by working with a high-priced financial advisor. This advisor charged investors anywhere from 1-1.5% to invest according to the factors. However, in all of the glossy marketing material they showed you, they failed to include those fees, which comes directly out of your returns, in the analysis. After fees, any premiums that factor investors achieved were eaten away, leaving investors with portfolios that contained significant tracking error, high costs, and lower than market returns.

For example, a sample factor portfolio held for two decades from 2003-2023 achieved a return of 10.18%, less the advisory fee and additional fund fees of 1.3% on average, that return drops to 8.88%. An investor on the contrary who just bought and held the market factor through a total market index fund, such as the Vanguard Total Stock Market Index (VTSAX) for a mere 0.03% fee would have achieved returns during this period of 10.53% beating the factor investor before fees and after fees.

Conclusion

I see a great number of discussions across social media, and the financial landscape about factor investing. Its believers speak of factor investing like it is a guarantee that tilting toward the “sources of outperformance” will lead to capturing alpha. I believe a more balanced approach is necessary, being tethered to no specific viewpoint, and allowing the evidence to inform our views seems a better approach to the discussion. Yes, there is a great deal of evidence from Fama and French, Carhart, and others that point to risk premiums in some periods of time. These premiums were robust and global in nature during the periods studied.

Conversely, other research has questioned this finding with its own data to back the view that risk factors may provide little to no alpha. It is important to understand that asset returns are a product of the specific characteristics of the time periods in which they take place. There is nothing predictive about the future that we can take from the past, and anyone who claims to be able to predict the future is likely trying to sell you something.

It is important that investors who choose to pursue factor investing realize that there is a sizeable premium in going from the risk-free rate (RFR) to the Market factor (Rmkt). Anything beyond this is an active bet.

In some time periods we have seen sizeable premiums for size (SMB) and value (HML), and in other periods we have seen significant underperformance for investors portfolios who deviated from the market portfolio to tilt towards these factors.

Morningstar

For example, the last 20 years has seen negative alpha from tilting towards the size and value factor. Many adherents to factor investing are gorging on both, sure they have “higher expected returns.” But is there any guarantee that value will beat growth going forward? No, and 20 years is a long time to sit and wait with no end in sight, paying higher fees with the hopes of capturing alpha from these risk factors.

An additional consideration is cost. Factor investing costs a great deal more to pursue, especially if you do so with an advisor. Creating a DIY portfolio of factor funds will cost you around 700% more than buying market weighted index funds such as the total market portfolio. If you use an advisor, this number jumps to somewhere near 4,000% more expensive than simply owning the market portfolio.

The evidence indicates that investors should hold the market portfolio, any decision to tilt towards factors has to be understood as an active bet that may or may not pay off and comes with higher costs. No one knows the future, and though factor advisors are quick to speak of the expected higher returns and the “better investment experience” that comes from targeting factors, the data disagrees. Many times, these results are rigged to make their strategies look better than they are. They cherry pick time periods, use non-investable indexes that have their methodology altered over time, thus distorting the returns which are shown without their fees being deducted.

But tell this to a factor-based advisor, and they will be quick to show you 100-year return charts and other marketing material. Be cautious when you see their slick marketing, and back tested results. Here is an example from DFA’s own disclosures on their equity balanced strategy index. It is clear from reading these disclosures that the results were back tested, and the methodologies even changed in the middle of the race. It is important for investors to be skeptical when the track record for these strategies is limited and they have to resort to back tested analysis for their marketing material.

Twitter/X Twitter/X Twitter/X

It is important, for beginning investors especially, to understand that if you simply start investing in total market index funds with rock bottom fees, you are well on your way to reaching your financial goals. Adding any additional factor positioning is a secondary conversation.

Fidelity Investments

This is not a piece telling investors to avoid factor investing. If you read the research yourself and want to tilt your portfolio towards these factors, there are a range of funds available for you to do that. Personally, I would choose Avantis, who are part of American Century Investments, or Dimensional Fund Advisors new ETF lineup, which provide a cost-effective way to implement these strategies, including single fund total portfolio solutions. Vanguard also has a line of factor strategies that are worth considering at an even lower cost. These factor funds are some of the best around, in my opinion, at targeting the factors, and ensuring you are getting what you pay for, while still keeping costs low.

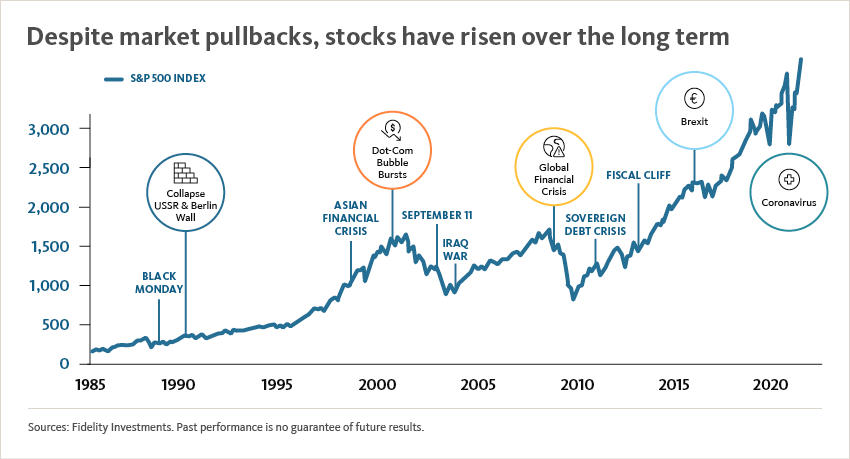

But the data is clear, the most additional expected returns can be found in moving from the risk-free rate to the market factor. So, for most investors, owning a simple total stock market index fund from Vanguard (VTSAX), for example, and investing and holding it consistently through the ups and downs of the market will likely be enough for you to achieve your financial goals.

Read the full article here