How much do we care about global warming? In theory, 93% of European Union citizens believe climate change is a serious threat, and 67% believe national governments are not doing enough to tackle it. In practice, however, European voters are punishing governments for their efforts to reduce emissions. Anti-green parties in Germany and the Netherlands are siphoning votes by opposing mandated emission cuts. Meanwhile, Sweden’s ruling coalition is cutting fossil fuel taxes to appease voters.

Europeans seem to want a solution to climate change, but only if they don’t have to pay for it. Indeed, Ipsos polling suggests that less than a third of EU citizens would pay more in income taxes to prevent climate change. For comparison, a University of Chicago poll finds that just 38% of Americans would be willing to pay a $1 monthly carbon fee to reduce emissions, down 14 percentage points from two years ago.

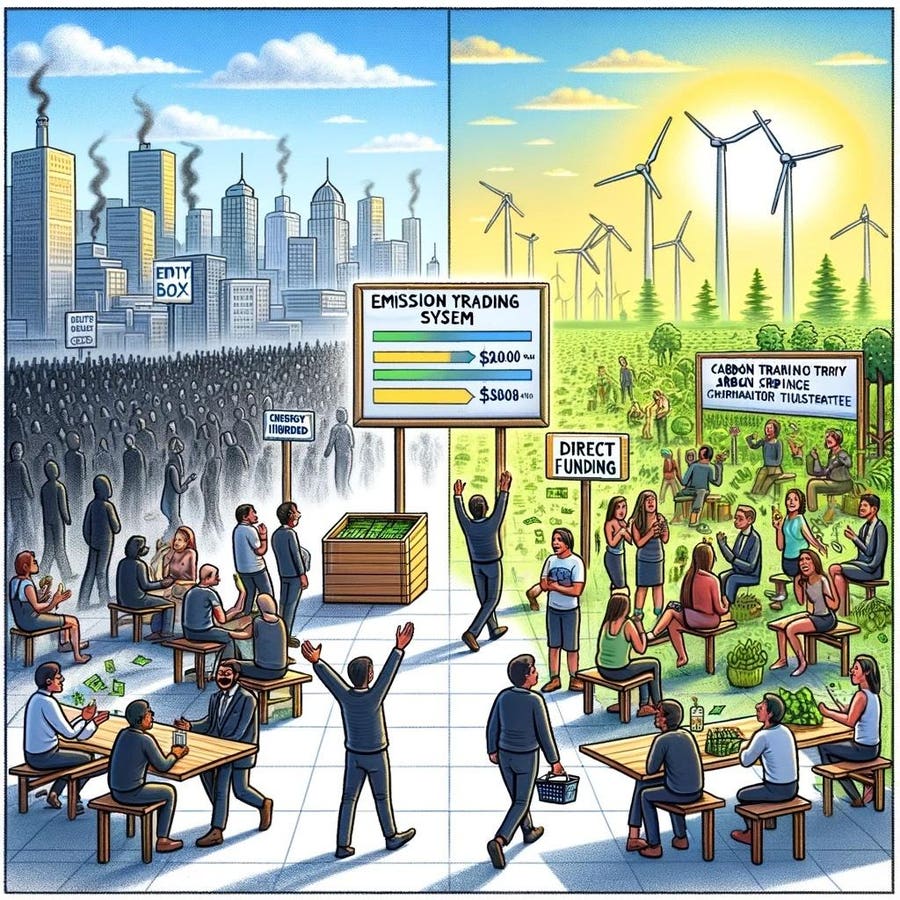

Clearly, political parties that wish to remain in power will have to back off decarbonization by decree. Instead, they will have to rely on market-based solutions like emissions trading systems (ETSs).

But are ETSs up to the job of holding climate change to 1.5° C? While carbon markets have immense potential to curb emissions, current iterations suffer from a litany of perverse incentives and unintended consequences. Let’s consider the limitations of the world’s posterchild ETS—the European Union’s Emissions Trading System—and then identify refinements that will equip ETSs to win the war against climate change. With COP28 starting November 30 in Dubai, now is the time to build global consensus for bold reforms in our carbon markets.

Fit for nothing?

For context, ETSs use a cap-and-trade policy: emission limits are set, free credits are allocated and fines are issued if a company emits more carbon than they’re allotted. Companies that reduce carbon usage avoid having to buy credits and profit by selling excess credits to companies that have exceeded their allowance. Ideally, this incentivizes companies to adopt cleaner technologies. In practice, however, it seems ETSs often enable firms to foist carbon costs onto their customers while carrying on as usual.

And the reach of these systems is growing. When the EU’s ETS debuted in 2005, it only covered emissions from heat and electricity generation, energy-intensive industries, aviation and maritime transport. But now, the EU’s Fit for 55 initiative, adopted in April 2022, aims to secure a 55% reduction in emissions by 2030 through adding cap-and-trade for buildings, transportation and fuels.

Cambridge Econometrics, a policy analysis firm, finds that Fit for 55 will increase gas-fueled household heating prices by 30% on average and raise the cost to fill a petrol vehicle by 16%. That is precisely the type of outcome that leads voters to reject state-lead climate policies.

To mollify critics, EU members are creating a $150+ billion Social Climate Fund that will “cut bills for vulnerable households and small businesses” according to European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. Effectively, the EU is taxing emitters and giving the proceeds to consumers to pay back to the emitters. In October, Canada did likewise by exempting households in Atlantic Canada from the carbon tax on their home heating bills. This is a pointless circular exchange of funds. Moreover, why would fossil fuel companies invest in decarbonization when governments subsidize the purchase of their dirty products?

A hole in the bucket

Another unintended consequence of carbon pricing and cap and trade is carbon leakage, which occurs when carbon prices rise so high that heavy emitters relocate abroad to avoid the costs. Of course, jobs and tax revenue leak out alongside the emitters.

For a while, fears of leakage from the EU ETS were mild, especially after a 2019 analysis found no evidence for it. However, in 2019 when the paper was published, the cost of an EU allowance peaked at €29 per metric ton. Since then, allowances have nearly tripled to €84. The higher the cost of an allowance, the more incentivized companies are to relocate to nations without ETSs or carbon taxes.

To curb leakage, the EU hands out free carbon credits to sectors at the greatest risk of leaving the EU. These sectors include oil refining, mining, petrochemicals, cement and coke oven products like steel. In other words, cleaner sectors pay for every cent of carbon they emit while the dirtiest industries are coddled. The free allowance will wind down to zero in 2034, by which point a 1.5° C world will be far gone. And at that juncture, why wouldn’t companies relocate to unregulated nations to take advantage of the lower costs, turning an emissions reduction plan into a not-in-my-backyard plan?

Is this thing even on?

Officially, emissions in sectors covered by the EU’s ETS have dropped by 43% since 2005. Yet, it is unclear whether the ETS even caused these emission reductions. Other incentives including feed-in tariffs, green certificates and the Large Combustion Plant Directive may deserve more of the credit. Because so many climate policies operate simultaneously, it’s difficult if not impossible to attribute the impact to any single initiative.

If we’re not even certain ETSs work, why are they still growing in popularity? The answer is efficiency. Government agencies are not investment firms. They struggle to find and fund the most efficient carbon-reducing technologies throughout the economy. The inherent greed of the free market is more efficient. It can drive capital to the technologies that result in the cheapest ton of CO2, saving taxpayer dollars and expediting the green transition.

ETSs distribute carbon costs based on a firm’s performance rather than government stewardship, incentivizing innovation. This enables investments like point-source carbon capture, which may provide little benefit to a firm’s bottom line but could have a tremendous impact on the environment. While decrees offer only sticks, ETSs provide carrots. No wonder that ETSs remain the most compelling way to incentivize decarbonization.

We need an air-tight carbon market

Despite ETSs current popularity, they need several refinements to prevent industries from leaking into less regulated markets or getting subsidies for dirty products. Heavy emitters will have to be whipped into shape and incentivized to adopt the most direct and measurable forms of decarbonization.

To achieve that, governments must collaborate on either a global ETS scheme or a minimum global carbon tax to disincentivize leakage. Recall that in 2021, 140 nations rallied around a plan to close off tax havens and institute a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15%. An excellent example! It’s time we close the carbon havens. Where better than COP28 to advocate for these improvements?

Heavy emitters should pay fully for the planetary damage they cause. And given that credits are prone to corruption, ETSs should provide stronger incentives to reduce or prevent emissions instead of merely buying credits. For example, a coal-fired power plant that invests in point-source carbon capture does more to mitigate emissions than a power plant that pays an organization to plant trees (which might burn down anyway). Paying someone else to build a green business isn’t equivalent to eliminating your business’s emissions.

Also important is to ensure that carbon costs are not merely passed onto consumers of inelastic goods like power and heating. Governments need to stop subsidizing consumer carbon emissions and instead subsidize adoption of technologies like electric vehicles, geothermal heating and heat pumps that reduce dependence on fossil fuels.

Without such incentives, the war on carbon may soon be lost. Although the odds are daunting, we have a responsibility to try everything possible, everywhere, to avoid the earth-shattering consequences of unchecked climate change. The dramatic climate events we have seen in recent years may just be a harbinger of bigger calamities to come, especially if global temperatures rise beyond 2° C.

The public has spoken. Though concerned about climate change, citizens will reject policies that spare heavy emitters from accountability while raising the cost of living for households. ETSs remain the best possible alternative that could have real impact. Let’s recreate carbon markets to achieve what decarbonization by decree has not: a good future for our children.

Read the full article here