The following segment was excerpted from this fund letter.

Danaher Corporation (NYSE:DHR)

One of the companies we have studied for many years, patiently waiting for the opportunity, finally gave us what we were looking for: Danaher Corporation. During the second quarter we bought a sizable amount of Danaher. We have analyzed the company, its spun off entities and studied its history over the years, though we had never purchased shares. This was partly due to questions about company end-markets and valuation, and partly due to impatience on our part. Sometimes certain opportunities simply fall into place.

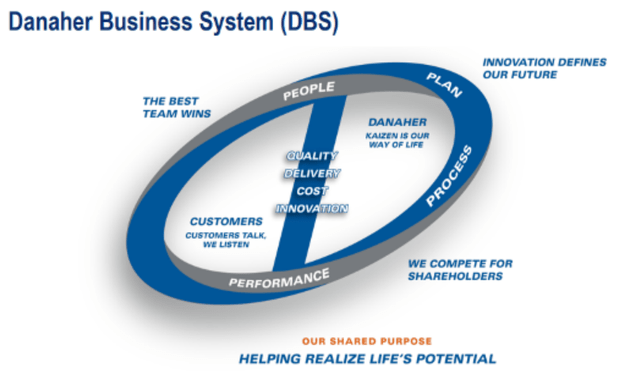

During several of our recent letters we have articulated and explained our interest in the life science space, especially the tools and instruments companies and Danaher happens to be perhaps the premier asset in the space. Before explaining why, it is worth highlighting why Danaher has been a company of interest for so long. Danaher was founded by brothers Steven and Mitchell Rales in 1984. The brothers focused on acquiring manufacturing companies and applying their version of Japanese kaizen in a process they named the Danaher Business System (DBS). DBS is described by Danaher as follows:

…the DBS engine drives the company through a never-ending cycle of change and improvement: exceptional PEOPLE develop outstanding PLANS and execute them using world-class tools to construct sustainable PROCESSES, resulting in superior PERFORMANCE. Superior performance and high expectations attract exceptional people, who continue the cycle. Guiding all efforts is a simple philosophy rooted in four customer-facing priorities: Quality, Delivery, Cost, and Innovation.[1].

Danaher is structured as a holding company/conglomerate, focused on continually deploying retained earnings into new businesses. As the company evolved and matured, the focus on manufacturing broadened in end-market terms and narrowed in its affinity towards growing end-markets and high recurring revenues. This led Danaher into the life science space, where the razor-blade business model is especially prevalent.

- We mentioned that Danaher today is a premier life science company and this resulted from an acquisition closed shortly before COVID began. Larry Culp had retired as Danaher’s CEO in 2015, before joining GE in 2018. Within a year of taking the reigns at GE, Culp sold Danaher GE’s Biopharma business for net proceeds of $20[2] This move was interesting to us for two reasons: It was transformational for Danaher in making life sciences the company’s largest and fastest growing end-market.

- It was transformational for Danaher in making life sciences the company’s largest and fastest growing end-market.

It was transformational for Danaher in making life sciences the company’s largest and fastest growing end-market. It was Culp specifically who led Danaher down the road into life science with a series of acquisitions over his decade and half tenure, including assets like Leica Microsytems and Beckman Coulter. This almost seems like a parting gift.

With life science tools and instruments now the company’s largest end market, the stage was set to focus on the company. For most of its history, Danaher had functioned as a traditional conglomerate–acquiring assets without truly integrating them–while operating in an unconventional manner. DBS is at the heart of what makes Danaher unconventional, but the company has also been willing to divest and spin assets to reinvent itself around a core focus. Danaher’s push into a pure-play life science company was cemented with the announcement in late 2022 that it would spin off its Environment and Applied Solutions segment into a standalone company since named Veralto (VLTO). The confluence of Danaher’s pure-play life science phase of its life and our intrigue in the sector situated us perfectly to capitalize on the opportunity. Our excitement was piqued as Danaher’s stock suffered through most of the first half of this year on falling revenue expectations in life sciences. There were three primary culprits behind the slowdown:

- Lower demand for the COVID-19 vaccine and COVID-related diagnostics

- Falling funding at early-staged biotechs, leading to lower levels of spend on new instrumentation and consumables

- Slowing demand from CDMOs (the companies who manufacture most biologics) due to the burn down of excess inventories built up during the COVID supply chain crisis

We will focus the majority of our conversation below on this third bullet, as in our estimation it has been most impactful and it pertains most directly to the piece of Danaher we find most alluring–the Biotechnology segment comprised of Cytiva, which as of today is the combined GE Biopharma (2020) and Pall (2015) acquisitions. Bioprocessing is the manufacturing process through which a cell or cells are scaled up in number in order to filter out and then, harvest specific pieces or output of the cells themselves. This is the process through which biologics, vaccines and now increasingly cell and gene therapies are made through. It is an oligopolistic market, with a small number of critical players and extremely high barriers to entry—two to four companies compete in any one of the key sub-segments. Danaher owns anywhere from 35-40% market share in the industry.[3] Although many fawn over the criticality of a company like ASML in empowering the semiconductor industry, the bioprocessors are similar for the biotechnology industry. The processes are complex, entailing both upstream and downstream components, with Cytiva the most comprehensive, vertically integrated and unique offering in the industry. Cytiva is especially dominant downstream, where bioprocessors make the most money and margin and the offering is truly differentiated. Moreover, once a pharma or biotech commences their clinical process with Cytiva’s components, those pieces become “spec’d in” guaranteeing a long-term revenue stream. These are predominantly consumable revenues by nature with over 75% of revenues derived from recurring sources.

Danaher closed the GE Biopharma (Cytiva) acquisition on the eve of the COVID pandemic. Typically, Danaher would operate a large, acquired business as a standalone business unit; however, Pall and Cytiva have a high degree of customer and product overlap. The plan had been to integrate these two units; however, with COVID and the intense demand for bioprocessing product as well as the complex operating and supply chain environment, Danaher prioritized meeting customer needs over the planned integration. With COVID now behind us, supply chains largely in order and more balanced customer needs, Danaher is finally pursuing a true integration. This will unlock both short and long-term benefits. First, a unified salesforce and a better cross-sell motion will drive better sales; second, and more importantly, a unified R&D effort across upstream and downstream assets will allow for a more harmonized product roadmap that could truly solve some of the biomanufacturing industry’s foremost pain points. While it will take time for Danaher to realize these R&D advantages, we believe the longer-term benefits could be profound as Danaher now owns the most complete portfolio and can build out simpler, more harmonized workflows. In today’s myopic environment, few are focusing on this critical long-term evolution.

As revenue expectations have come down for Danaher and other bioprocessing companies, some of questioned whether these newly lowered expectations are the consequence of temporary forces that inevitably will recede or signs of a more permanent step-down from the double-digit growth rates witnessed over the last decade into a new-normal in the single digits. As we have pursued our work, the answer is clear in our minds that these forces are temporary rather than permanent, meanwhile the valuation of Danaher has moved to a point where it is reflecting a degree of permanence on an artificially low level of earnings.

The following summarizes the findings of our conversations with industry practitioners from the CDMO and biotech space. The typical CDMO contracts with its customer to what level of consumable inventory should be held over time. This was typically in the 6 month range, due to consistent volumes of biologic manufacturing and a two-year or less shelf-life on the critical pieces. This 6 month range was bumped to upwards of one year of inventory and in many cases nearly 18 months of inventory. Further, many put in for weekly orders on critical pieces when monthly orders formerly sufficed, as the more frequent cadence bumped the purchaser up the priority list at the vendor. These actions made sense during COVID when inconsistent supply chains imperiled the ability of some pharmaceutical and biotech companies to bring life-saving drugs to market.

The problem is that CDMOs and their customers made such agreements with hand-shake arrangements rather than formalized re-writes of their contracts and had no system in place to track inventory and to which customer’s account to attribute the purchase of standardized inventory pieces. Therefore, contractually, CDMOs were committed to purchasing certain volumes of consumables with the bioprocessing companies like Danaher; however, the CDMOs customers were theoretically responsible for reimbursing such purchases though not necessarily bound.

These problems were confounded by challenges at the FDA for the industry. Although COVID saw a surge in funding for the biotech industry, it created significant bottlenecks in development and approvals at the FDA. These forces have weighed on bioprocessing demand with a lag, as it resulted in a much slower pace moving indications through the clinic. The FDA is committed to resolving these problems and has expressed its intent on “if not exponential, at least some logarithmic progression towards more and more gene therapies being approved.”[4] Part of the improvement is facilitated by moving FDA staff off COVID-specific problems and approvals. Another key pillar is facilitating enhanced manufacturing processes and protocols, which would accrue benefits to the bioprocessing industry. Progress is already palpable with Sarepta’s Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy garnering FDA approval despite a panel initially recommending otherwise.[5]

As 2022 drew to a close, there was a sudden realization across the industry that a) supply chains had finally normalized; and b) given the normalization of supply chains there was far too much consumable inventory in the system. Before the bioprocessing companies truly caught wind of this, the CDMOs and pharma/biotech customers had to sort out who would pay the bill for in-place commitments and future were revised and renegotiated. Understanding these dynamics made clear to us that it was difficult for the bioprocessors to get visibility into the trends as they stand today; however, triangulating with other industry reference points, it equally became clear that strong growth for the industry was truly a “when not if question.” We find such setups incredibly attractive given the obsession of most market participants with identifying the precise timing of an inflection. Importantly, several key forces align to suggest this inflection will take shape sooner rather than later. These include:

- A normalization of inventories and return to steady-state consumable purchases.

- Accelerating FDA approvals, breaking the COVID-induced slowdown, which has weighed on the last several years of activity. Approvals are running well ahead of 2022’s painfully slow pace, especially strong in biologics which have a more pronounced revenue impact for the bioprocessors.[6]

- Biologic prescription volumes troughed in the Summer of 2022 and now are accelerating comfortable into double-digit year-over-year growth. Importantly, prescription volumes translate nicely into accelerating volume needs, supporting consumables demand.

- Moving beyond COVID vaccine-related demand from challenging year-over-year comparables

- Rapid uptake of GLP-1 inhibitors which both drives increased investment needed to support demand and increased investment from competitive offerings (same targets, new formulations as well as additional targets) and Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk investing their proceeds in novel areas. Plus, from a sentiment perspective the success of GLP-1 inhibitors hammers home how much meaningful change for humanity and investors alike comes from the biotech sector.

Breakthroughs during COVID in modalities like mRNA, with a clinical pipeline in the space that never would have happened otherwise, which will reach more mature and volume-demanding stages of the clinical development curve in the 2025-26 timeframe. In fact, several industry experts we spoke to think this cyclical downturn today might sow the stages for overly tight supplies as growth surges for consumables demand accompanying clinical maturation. The above explains our attraction to the bioprocessing space. Below let us point out the specific reasons why we centered our interest on Danaher in particular:

- History: Danaher has a long history of prudent capital allocation and this is an outstanding moment in time for acquisitions in the life sciences.

- Philosophy: centered around a unique and proven operating philosophy (DBS).

- Timeliness: Danaher will spin off the non-life science assets at the end of the third quarter and become a pure-play in the sector for the first time in its history. More importantly, Danaher is strategically integrating Pall and Cytiva for a unified go-to-market motion.

- Valuation: Post Veralto spin, Danaher is trading for approximately 21x our view of normalized earnings, which is at a slight premium to a market multiple for a company that will grow at a far swifter pace, for a longer duration. Further, this 21x is understated given the high component of amortization in Danaher’s reported earnings that stems from their acquisition-heavy strategy. Amortization alone adds up to about $1.90 hit to EPS, which would reduce the P/E ratio by upwards of 3 turns. In Danaher’s case, we think EBITDA is a great proxy for true earnings power and free cash flow generation. If we stack up the last three full years of EBITDA (2020-2022) post-spin and after expensing corporate overhead, the company trades for an EV to average EBITDA of 18.38x. Essentially, when viewed through this prism, between normalized earnings power and looking past non-cash amortization, the business trades at a slightly below S&P earnings multiple for a much better quality and growth profile with an inevitable cyclical upturn looming ahead.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Read the full article here