Introduction

Cassava Sciences (NASDAQ:SAVA), a clinical-stage biotechnology company, was established in 1998 by Remi Barbier, the current CEO, from the modest beginnings of his living room. Before rebranding in 2019, the company was known as Pain Therapeutics, Inc., which during its nearly two decades of operation experienced a significant loss, seeing a 99% reduction in market capitalization. Following its rebranding, Cassava Sciences shifted its primary focus to Alzheimer’s disease (‘AD’), with a single molecule in their pipeline – Simufilam (previously referred to as PTI-125). In addition to Simufilam, the company is also developing a diagnostic tool for AD called SavaDx, but they emphasize that it is a secondary priority compared to their therapeutic drug.

We decided to allocate our resources to analyze Cassava Sciences for multiple reasons. AD is a neurodegenerative condition with few treatment options and a significant potential addressable market. Drug approvals in the AD sector are newsworthy events that can lead to substantial sales. Simufilam is crucial to the company’s future. Its approval, if supported by strong data, could result in a multi-billion-dollar market capitalization and possibly an acquisition. On the other hand, its failure could reduce the company’s value to its cash reserve or less.

Cassava Sciences has been the center of controversy due to allegations and questions surrounding the science behind its drug. We recommend that readers briefly review the allegations against Cassava and the regulatory landscape for AD, as we will primarily focus on clinical trials analysis and company valuation. Simufilam data will ultimately determine the company’s future. We believe that the company has a high chance of success, provided that no legal proceedings find evidence of misconduct.

Simufilam

Simufilam is designed to interact with a misfolded form of the Filamin A protein (FLNA). By binding to FLNA, Simufilam is thought to restore its proper shape and thereby reduce the Aβ42-α7nACh receptor (α7nAChR) interaction, curtailing the pathological progression of AD.

The α7nAChR itself is not a novel target in Alzheimer’s research; it has been implicated in the disease for many years, and numerous trials have attempted to address AD by targeting this receptor. However, due to the picomolar binding affinity of Aβ42, these efforts have not yielded significant efficacy. Simufilam, by modulating the FLNA protein, may offer a different approach that could potentially protect neurons from degeneration and improve cognitive outcomes for patients with AD. The molecule has been shown to reduce the association between FLNA and α7nAChR by 60-75% in rat models. Moreover, the molecule was reported to decrease the binding affinity of Aβ42 to the receptor by a factor of 1,000 in post-mortem tissue and by 10,000 in SK-N-MC cell lines. If accurate, this could bring Aβ42 affinity to the nanomolar range, where acetylcholine could potentially outcompete the protein. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that Simufilam’s effects were not investigated concerning two other molecules- Neuroligin-1 and PrPc-that are known to interact with Aβ42 in neurodegenerative diseases (both exhibit nanomolar affinities).

Preclinical models tend to show trends that are not always replicated in human trials. Cassava has ongoing, and completed clinical trials, which investigate the drug efficacy in AD patients.

Clinical Data

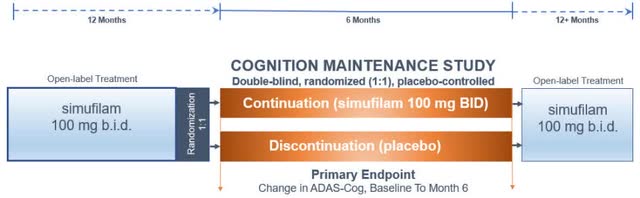

Cassava Sciences has conducted several clinical trials to evaluate Simufilam. Initially, the drug underwent a small Phase 1 (NCT04932655) study in healthy volunteers to assess safety and pharmacokinetics (PK). Subsequently, Phase 2a (NCT03748706) and 2b (NCT04079803) studies were initiated with AD patients, focusing not only on safety, but also on the analysis of biomarkers. After consultations with the FDA and obtaining a Special Protocol Assessment for their Phase 3 studies-RETHINK-ALZ and REFOCUS-ALZ-Cassava carried out an additional Phase 2 12-month open-label trial. This was followed by a 6-month randomized withdrawal trial known as the Cognition Maintenance Study (CMS). The REFOCUS-ALZ trial, a Phase 3 (NCT05026177) 18-month study, completed enrollment in October 2023 with 1,125 participants. The anticipated time for reporting top-line data is mid-2025. The RETHINK-ALZ trial, another Phase 3 (NCT04994483) study but with a 12-month duration, also completed enrollment in October 2023 with 804 participants, and its top-line data is expected in the fourth quarter of 2024.

In phase 2a (n=13) the company reported following findings before and after 28 days of treatment with Simufilam (100mg twice a day):

|

Total Tau |

P-tau |

NfL |

Neurogranin |

YKL-40 |

IL-6 |

IL-1β |

TNFα |

p-tau/Aβ42 ratio |

|

-20% |

-34% |

-22% |

-32% |

-9% |

-14% |

-11% |

-5% |

improved |

Reduction in disease related biomarkers was observed. The study was open-label and had a small sample size. No assessment of cognitive function was conducted, and the analysis featured only one 28-day period.

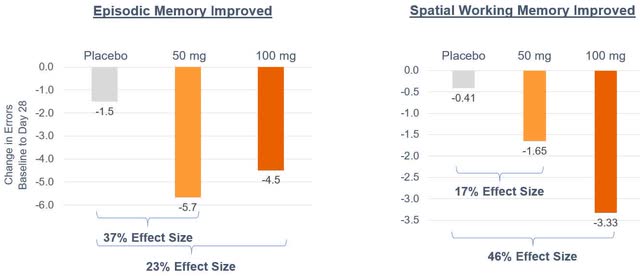

In phase 2b (n=64) the company reported findings on biomarkers, Episodic Memory and Spatial Working Memory before and after 28 days of treatment with Simufilam or Placebo (50mg or 100mg twice a day).

|

Total Tau |

P-tau |

Aβ42 |

Neurogranin |

NfL |

IL-6 |

YKL-40 |

sTREM2 |

HMGB1 |

|

-15%/-18% |

-8%/-11% |

+17%/+14% |

-36%/-43% |

-28%/-34% |

-10%/-11% |

-10%/-12% |

-43%/-46% |

-32%/-32% |

(note: figures are reported as 50mg/100mg)

Surprisingly, doubling the dose of Simufilam did not lead to significantly greater reductions or improvements in biomarkers. This outcome could suggest that the benefits of the 100 mg dose may only be marginally better than the 50 mg dose. Nonetheless, the drug was deemed to have a favorable safety profile.

The episodic memory and spatial working memory data was summarized by the company in the following figures.

Cassava Sciences

The observed effect of Simufilam, while noteworthy, holds limited prognostic significance due to the nature of the study being small-scale and open-label. Additionally, the inconsistency in the drug’s impact on Episodic Memory and Spatial Working Memory between the lower and higher doses may indicate potential flaws in the study design and the possibility of biased data. The admission criteria for patients in the Phase 2a and 2b studies could also introduce confounding variables; patients were included based on a clinical diagnosis of dementia due to possible or probable AD, which may not have been completely accurate. The CEO of Cassava Sciences has highlighted in various interviews that a persistent issue with AD trials is the inclusion of patients who exhibit clinical symptoms of AD but do not actually have the underlying pathophysiology. He estimates that this misdiagnosed population could account for 20% to 30% of participants in such trials.

The first trial by Cassava that included an analysis of cognitive function, specifically using the ADAS-cog Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-cog) measurements, was reported in 2023. The top-line data from this 12-month open-label study in mild to moderate AD (n=216), started considerable debate due to various inconsistencies and confusing aspects of the reported results.

|

n=216 |

Baseline |

Month 12 |

Change |

|

ADAS-Cog11 |

19.1 (9.2) |

19.6 (13.3) |

+0.5 |

|

MMSE |

21.5 (3.6) |

20.2 (6.4) |

-1.3 |

|

NPI10 |

3.2 (4.6) |

2.9 (4.6) |

-0.3 |

|

GDS |

1.8 (1.8) |

1.4 (1.9) |

+0.4 |

During the 12-month study period, SAVA reported a slight decline in cognition, indicated by an increase of +0.5 points on the ADAS-cog scale, and a worsening of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score by -1.3 points. Despite this decline, when compared to the historical rates in patients with mild to moderate AD, these results could be interpreted as notable. Cassava posits these findings as evidence of Simufilam’s efficacy, suggesting that while the drug may not improve cognitive function, it appears to slow or halt its decline, which is a significant feat in the management of AD. To strengthen their case, the company provided additional data comparing the drug’s effects on patients with mild versus moderate AD, demonstrating that Simufilam seems to exert a more pronounced effect in those with milder forms of the disease.

|

n=216 |

Baseline |

Month 12 |

Change |

|

Mild ADAS-Cog11 |

15.0 (6.3) |

12.6 (7.8) |

-2.4 |

|

Moderate ADAS-Cog11 |

25.7 (9.2) |

30.1 (13.1) |

+4.4 |

Moderate patients seem to not respond to Simufilam, even in an open-label study. The rate of decline is similar to historic placebo decline rates.

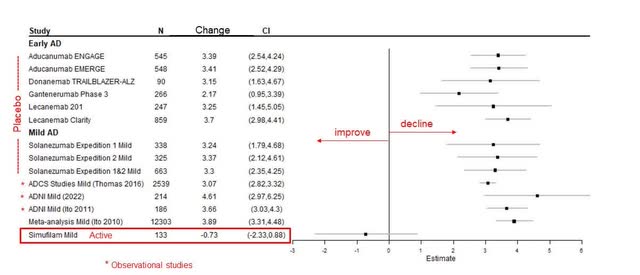

Cassava Sciences

The reported high standard deviation (SD) in the results emphasizes a significant variability, suggesting a more dispersed and potentially random pattern of outcomes. However, it was observed that the subgroup of patients with mild AD showed an improvement in cognition, a finding that carries potential promise. Despite this, some critics have expressed skepticism about the reported rates of cognitive decline, pointing out the potential confounding effects of ongoing treatments with Memantine or AChE inhibitors.

The inclusion criteria for the trial stipulated that subjects must have been on a stable dose of Memantine, Rivastigmine, Galantamine, or an AChE inhibitor for at least 3 months prior to screening, which implies prior use beyond the 90-day mark. Considering that symptomatic treatments for AD often yield benefits that diminish over time, the confounding impact on the study’s data from these medications should theoretically be minimized. In our analysis and model estimates, we have accounted for the potential bias that such confounding factors could introduce.

The cognitive improvement reported for the mild AD group, indicated by a change of -0.73 on the cognitive scale, is intriguing because it is less substantial than previously reported improvements. Cassava did not address this discrepancy. Given the population size of 133 for the mild group, it is possible to estimate the proportion of mild and moderate patients in the study. The mild patients comprised approximately 62% of the study’s population, while the remaining 38% were patients with moderate AD.

SAVA also shared biomarker data collected from 25 patients at 6-month mark. The results are presented in the following table.

|

Total tau |

P-tau181 |

Neurogranin |

NfL |

sTREM2 |

YKL-40 |

|

-38% |

-18% |

-72% |

-55% |

-65% |

-44% |

The improvements seen across various biomarkers in the data from the Phase 2b study over a 12-month period are encouraging when compared to the 28-day results. The most noteworthy changes pertain to the biomarkers closely linked with neuronal degeneration, namely total tau and phosphorylated tau (p-tau), which seem to validate the drug’s proposed mechanism of action (MOA).

A 38% reduction in t-tau is particularly significant as it is thought to reflect active neuronal degeneration at a given time. This aligns with Simufilam’s MOA, which involves reducing the α7nAChR receptor’s affinity for Aβ42, potentially mitigating further t-tau deposition. However, Simufilam is not associated with the removal of pre-existing phosphorylated plaques, which is why the p-tau reduction, although present, is more modest. P-tau levels are considered indicative of the accumulated burden of AD tau pathology over time. Since Simufilam does not reverse existing damage, the smaller reduction in p-tau levels aligns with expectations.

Other biomarkers, including Neurogranin (Ngr), Neurofilament Light Chain (NfL), sTREM2, and YKL-40, show more substantial reductions. Ngr and NfL correlate with the progression from mild cognitive impairment to AD dementia, and their reduction may correspond to slower cognitive decline. sTREM2 and YKL-40 are involved in neuroinflammation, and their decrease could signal reduced brain tissue stress.

It is important to recognize that the biomarker landscape in AD is still an emerging field, with some results being counterintuitive-for example, varying sTREM2 levels among genetic variants of AD and one study’s finding that higher sTREM2 may be linked to slower cognitive decline. Additionally, AD biomarkers are confounded by other age-related pathologies, limiting their predictive value for treatment efficacy and cognitive decline or improvement rates.

The phrase “biomarkers do not lie” is often reiterated by Cassava and its investors, and while biomarkers indeed reflect biological processes accurately, the complex physiology of AD and the many as-yet-unexplored molecular interactions complicate their predictive capabilities. In essence, while biomarkers are truthful, they may not always be informative. Despite these complexities, Simufilam is reported to have a favorable safety profile.

The CMS study was designed as a follow up to the open-label phase 2 study, to assess the drug effect over 6 months in patients that completed 12 months of Simufilam treatment. Patients were randomized to either continue treatment with the drug or to take placebo. The following figure from the trial design was published by Cassava.

Cassava Sciences

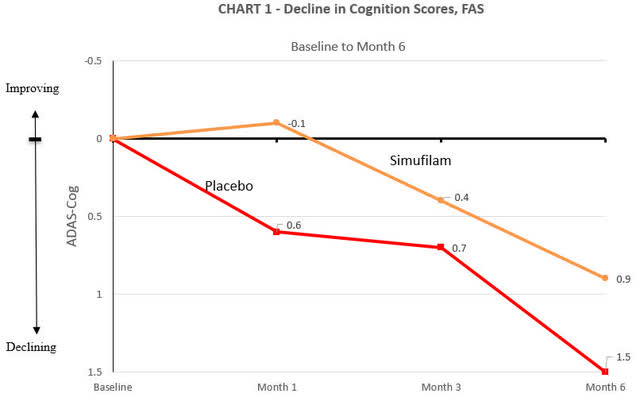

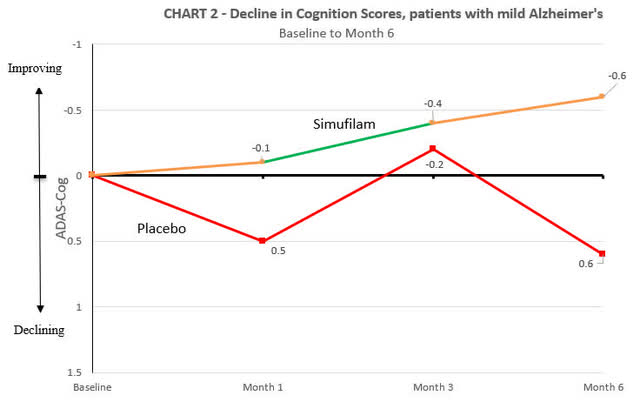

The company reported topline results in Q223 10-K filling, on top of the ADAS-cog analysis of change from baseline to month 6 in the entire population, they also published data of the mild subpopulation.

|

n=157 |

Simufilam |

Placebo |

|

ADAS-cog |

+0.9 |

+1.5 |

|

Mild ADAS-cog |

-0.6 |

+0.6 |

The company additionally attached figures that show ADAS-cog change at month 1, 3 and 6.

Cassava Sciences

Cassava Sciences

In the trial, both the placebo and Simufilam treatment arms experienced a decline in cognitive function. The decline in the Simufilam arm was marginally slower, yet, when considering standard deviation values typical of a large AD trial (around 6), this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.53). Cassava Sciences characterized this marginal difference as a “38% reduction compared to placebo.” While this statement is technically accurate, the use of percentage values can be seen as somewhat misleading because they express a relative change without context to the actual efficacy.

Cassava also released baseline statistics for both the overall population and the mild subgroup. The baseline MMSE was slightly higher in the Simufilam group (18.6) compared to the placebo group (18.1), and a similar pattern was observed for the baseline ADAS-cog scores, with the Simufilam group at 19.3 and the placebo group at 21.9. Although these differences may seem minor, they could influence perceptions of the drug’s efficacy, which some might consider as marginal as the results themselves.

For the mild subgroup, baseline MMSE scores were nearly identical (24.1 for the placebo group vs. 24.0 for Simufilam), and baseline ADAS-cog scores were close as well (11.0 for placebo vs. 11.2 for Simufilam). Cassava claimed an “205% improvement compared to placebo” in this subgroup, which is actually a 200% improvement, again demonstrating the use of technically correct (almost) but potentially confusing statistics.

An interesting point to note is that at the 3-month mark, the Simufilam and placebo groups had nearly identical ADAS-cog changes. This convergence further complicates the interpretation of efficacy.

In a manner similar to their presentation of the Phase 2 data, SAVA included a figure comparing the historical decline of placebo groups with the data from the CMS. However, rather than presenting the changes from baseline to 6 months, they showcased the data over an 18-month period, combining the results from the Phase 2 open-label study with the CMS. This was specifically for the mild Alzheimer’s disease subgroup, which included 77 participants.

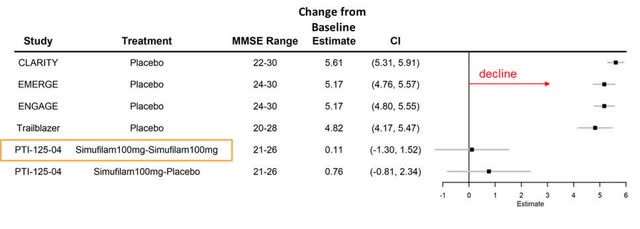

Cassava Sciences

Based on the data provided, in the 18-month period of the study, the group that continued on Simufilam experienced a marginal decline of +0.11 points, while the group that switched from Simufilam to placebo for the follow-up period showed a decline of +0.76 points. From these figures, we can backtrack to infer the changes observed at the 12-month mark for the mild AD patients.

For the Simufilam-continuous group (n=40), if the change from baseline to 18 months is +0.11 and the change from month 12 to month 18 is -0.6, then the calculated change from baseline to month 12 would be an increase of +0.71 points. For the placebo group (n=37), given the overall decline of 0.76 points by month 18 and the decline of 0.6 points between months 12 and 18, the change from baseline to month 12 would be an increase of +0.16 points. Averaging the changes for these two groups, both of which were part of the previous phase 2 study, yields an approximate change of +0.45 points from baseline to month 12.

Considering that 77 patients represent slightly more than half of the mild patient group from phase 2 (n=133), the remainder of the patients must have experienced a different trajectory. If the figure of -0.73 is accurate, these patients would have declined by approximately -1.1 points from baseline to month 12. Conversely, if the decline was as large as -2.4 points, the same subset would have had an average change of approximately -2.85 points from baseline to month 12. The latter scenario would indicate an extraordinary variance in response among patients at similar stages of the disease.

In any event, for patients with mild AD (with MMSE scores between 21-26), the anticipated average increase in ADAS-cog scores (indicating cognitive decline) in a placebo group over 12 months is typically between +3 to +4 points. Therefore, the reported figures from Cassava’s study represent a lesser decline than what is generally expected, suggesting a potential slowing of disease progression in the treated group.

The outcome of Phase 3 clinical trials will be critical for Cassava Sciences, as these results will shed light on the efficacy of Simufilam in a randomized controlled trial setting. The success or failure of these trials will be pivotal in making a case for FDA approval.

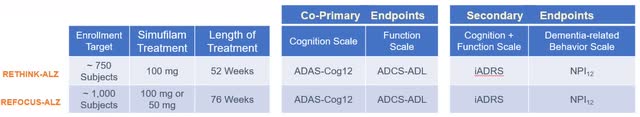

Both the FDA and Cassava have agreed upon the design of the trials, with both ADAS-Cog13 and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Activities of Daily Living Inventory (ADCS-ADL) set as co-primary endpoints. The trials will compare Simufilam, administered at 100mg twice daily, against a placebo.

Given the absence of data regarding ADCS-ADL scores in previous Simufilam studies and considering that both scales are co-primary endpoints, the focus will be on the ADAS-cog13 for analysis. It is understood that ADCS-ADL is moderately correlated with ADAS-cog.

In anticipation of the Phase 3 results, and to evaluate the regulatory prospects of the drug, an assessment based on the ADAS-cog13 data was conducted. RETHINK-ALZ and REFOCUS-ALZ were summarized by Cassava in following figure.

Cassava Sciences

RETHINK-ALZ is set to report topline data on 804 subjects assigned to a 1:1 regimen of Simufilam 100mg or a matching placebo, administered twice daily. The study’s duration is 12 months, and it is designed to measure the change from baseline figures over this period. The likelihood of the Phase 3 data reaching statistical significance hinges on several factors: the difference in changes between the treatment and placebo arms, the corresponding sample sizes, and the SDs. The sample size is established, with each group expected to comprise about 402 subjects. Estimating the SD is more challenging. We established that SDs in large-scale AD trials, such as EMERGE, ENGAGE, and TRAILBLAZER-ALZ, are typically reported to be between 6-7 for both the placebo and treatment arms. However, Cassava’s Phase 2 open-label trial indicated substantially higher SDs, up to 13.3, which might be attributed to a more pronounced effect in the mild AD subgroup. Assuming that the 60-70% ratio of mild to moderate subjects in the Phase 3 trials will be consistently applied to both arms, we project that the SD will be higher than the 6-7 reported in other trials but less than the 13.3 from the open-label study, due to the larger participant pool. For the purposes of this analysis, we will consider SD values between 9-11 for the treatment arm and between 6-7 for the placebo arm.

We anticipate that the results from the open-label Phase 2 study will not be exactly replicated in the Phase 3 trials. Although the biomarker data may remain consistent, the ADAS-cog scores are expected to be influenced by the rigorous blinding and randomization of the trial. Assuming the baseline characteristics are similar to those from the open-label study, we predict that the ADAS-Cog13 decline will range from +1 to +3 points for the treatment arm. The decline in the placebo group is expected to align with historical declines observed in subjects with baseline MMSE scores representative of those in the study. Following tables represent the best- and worst-case scenarios we predict.

|

n=804 |

Simufilam |

Placebo |

|

ADAS-Cog change |

+3 |

+3.5 |

|

SD |

11 |

6 |

|

p-value |

0.42 |

|

|

n=804 |

Simufilam |

Placebo |

|

ADAS-Cog change |

+1 |

+4 |

|

SD |

9 |

7 |

|

p-value |

<0.001 |

|

Given the various possible outcomes of Cassava’s Phase 3 trial, a comprehensive approach involves evaluating multiple scenarios, assuming equal probability. Our in-house quantitative model calculated the likelihood of achieving statistical significance in the ADAS-cog score of 63%. This estimation reflects assessment of the established data ranges. Additionally, we expect the biomarker results to be in line with those from the 12-month open-label trial, suggesting consistency in Simufilam’s effects.

REFOCUS-ALZ is set to report topline data on 1125 subjects assigned to a 1:1:1 regimen of 50mg Simufilam, 100mg Simufilam, or a matching placebo, administered twice daily. The study’s duration is 18 months, and it is designed to measure the change from baseline figures over this period. The primary endpoints for REFOCUS-ALZ are the same as those in the RETHINK-ALZ trial.

Given that the inclusion criteria are consistent with the 12-month Phase 3 study, similar results are expected, though with potentially slightly higher rates of cognitive decline due to the longer study period. Historical placebo decline rates over 18 months for patients with baseline MMSE scores of 22-24 are typically between +5 to +6 points. For the Simufilam arms, extrapolating from the CMS, where the 6-month rate of decline was +0.9, the expected 18-month decline for the 100mg arm would likely be between +2.5 to +4.5 points. The standard deviation is anticipated to be comparable to that of the RETHINK-ALZ trial.

Applying the same in-house quantitative model as used for the RETHINK-ALZ analysis, the likelihood of achieving statistical significance in the REFOCUS-ALZ study is estimated to be 80%.

Cassava Sciences appears to have developed a safe small molecule that is likely to show evidence of cognitive benefits for mild to moderate AD patients. The extent of the drug’s efficacy in the moderate patient group seems limited, suggesting that significant effects may be primarily observed in patients with mild AD. This aligns with the drug’s proposed mechanism of action and preclinical findings. Consequently, the FDA may grant approval for Simufilam specifically for this responding subpopulation.

The anticipation is that the Phase 3 trials have a high probability of producing significant results. Nonetheless, the presence of discrepancies in the data complicates the assessment of the drug’s true efficacy. While Cassava has faced accusations of academic misconduct, the company has maintained that the errors in preclinical publications did not impact the study outcomes or conclusions, and no evidence of fraud was reported. Additionally, the FDA’s denial of two petitions against the drug could indicate a lack of compelling evidence to halt its development, suggesting a regulatory confidence in the ongoing trials.

SAVA Valuation and Cash Burn

The commercial market for AD treatments is vast, and capturing even a fraction of it could lead to annual sales in the billions. However, gaining FDA approval is just one hurdle; a successful drug must also win over both physicians and patients. Recent approvals of anti-amyloid antibodies have been mired in controversy, particularly regarding their safety profiles. These concerns have had a tangible impact on their market performance, as evidenced by lower-than-expected annual sales figures. With estimated 55M cases worldwide and 6.7M in US alone, Simufilam sales could generate enormous returns for Cassava shareholders. Mild AD patients represent about half of cases, estimated at 2.5M-3M in US. If priced at a level competitive to recent approvals ($20,000-$25,000 per year), the drug value can be calculated via a NPV model (with expected patent expiry in 2033, and approval in 2026). We forecasted Simufilam capturing roughly 15% of the market (conservative) and quickly ramping the sales over a 2-year time period. The SG&A was set to 40% of sales (average for small biotech, a larger company can expect 20%), and the tax rate at 15%. The data is present in the table below (figures reported in millions).

|

Year |

2026 |

2027 |

2028 |

2029 |

2030 |

2031 |

2032 |

2033 |

2034 |

2035 |

|

Revenue |

500 |

2,500 |

7,500 |

7,425 |

7,351 |

7,277 |

7,204 |

432 |

22 |

1 |

|

SG&A |

200 |

1,000 |

3,000 |

2,970 |

2,940 |

2,911 |

2,882 |

173 |

9 |

0 |

|

Pretax |

300 |

1,500 |

4,500 |

4,455 |

4,410 |

4,366 |

4,323 |

259 |

13 |

1 |

|

Tax |

45 |

225 |

675 |

668 |

662 |

655 |

648 |

39 |

2 |

0 |

|

Net Income |

255 |

1,275 |

3,825 |

3,787 |

3,749 |

3,711 |

3,674 |

220 |

11 |

1 |

The NPV at 10% discount rate resulted in a value of $13.2B. This would correspond to $313.36 per share. While $13.2B might seem like a lot, it is less than what Biogen gained on Aducanumab in 2021. Needless to say, with its only other candidate in the pipeline being a biomarker test for AD, if Simufilam was to fail, we believe that the company would likely be valued at or below cash basis. As of today, that would correspond to $3.4 per share or less, but would likely be much lower (unless the company raises more money) close to data read-outs, due to cash burn.

Cassava Sciences has indicated in various 10-K filings the potential for executive compensation benefits tied to a merger or acquisition event. The CEO’s uncertainty about the company’s capacity to supply Simufilam to patients in the future may hint at an openness to acquisition. These signals suggest that if Simufilam proves successful, Cassava Sciences might position itself to be acquired by a larger pharmaceutical entity, which would have the resources to manufacture and distribute the drug at scale.

As of Q3 2023, Cassava holds a net cash reserve of approximately $142M. Extrapolating from recent cash burn rates ($75M throughout Q1-Q3 2023) and considering the company’s ongoing phase III trials, we project that Cassava may burn over $100M by the end of 2024. These figures indicate a significant reduction in their cash position, and will likely indicate a need for funds to complete the REFOCUS-ALZ study and proceed with regulatory path.

At present, Cassava has 42M outstanding shares. In May 2023, the company entered into an at-the-Market offering program, which allows for the sale of up to $200M dollars’ worth of shares through from time-to-time transactions. No sales were made to date. The company might likely utilize this possibility closer to the first phase 3 readout expected in October 2024, due to possible positive stock price movement.

Our Verdict

Cassava Sciences presents an intriguing case: it has a potentially groundbreaking small molecule in Simufilam, yet it is burdened by a problematic reputation. If Simufilam’s development is untainted by fraud or misconduct and the data continues to unfold favorably, we believe that the company’s stock is likely to reach multi-billion-dollar capitalization. The market skepticism and strong criticism directed at Cassava may be unwarranted. Despite the lawsuits and citizen petitions aimed at disrupting their drug development, no concrete evidence of misconduct has surfaced. Corrections have been made to their peer-reviewed publications, yet the core conclusions and findings remained unchanged. Oversight bodies and journal editorial teams have found no reason to discredit Cassava’s research, and the FDA has not impeded the drug’s progress. The consistency seen in Cassava’s preclinical research was also mirrored in their early phase II studies, further supporting the validity of their scientific approach.

The Phase 2 data from Cassava trial has its limitations, with potential biases arising from the small sample size, the open-label design, and the inclusion of symptomatic subjects who may not have pathologically confirmed AD. Furthermore, discrepancies in various measures cast doubt on the robustness of the results. Nevertheless, these Phase 2 results should not be disregarded entirely; rather, they should be viewed as a preliminary indicator of the drug’s potential efficacy, with the caveats of the study design taken into consideration in subsequent analyses.

The remarkable efficacy reported in the mild AD subgroup during the open-label trial, as opposed to the negligible effects seen in the moderate group, has influenced our conservative projections. These are grounded in the data from the Phase 2 open-label study and the CMS follow-up. Efforts have been made to account for several types of bias and to reconcile the inconsistencies in reporting.

While we maintain a cautious stance on the predictive value of biomarkers for cognitive outcomes-given their susceptibility to errors and the nascent state of the underlying research-we recognize changes in these markers as indicative of Simufilam’s therapeutic action. Biomarkers, despite the ongoing debate about their role, are seen as a positive signal of the drug’s biological activity, even if we do not heavily rely on them for our conclusions.

With the in-house quant-model estimates suggesting over a 60% and 80% likelihood of reaching statistical significance in the Phase 3 trials, there is a perspective that SAVA’s current market valuation might be conservative. However, we decided to hold off on purchasing stock at this time. Cassava’s challenges with transparency, potentially misleading reporting, and the shadow of ongoing lawsuits – outcomes that are anticipated in the near future – weigh against an immediate investment.

Should Cassava announce favorable conclusions to the ongoing lawsuits, it could catalyze a positive reaction in the stock market. Yet, given the current risk-reward balance, the potential gains from positive Phase 3 data – should they materialize – would likely offer a more substantial investment opportunity. Therefore, we give the stock a “hold” rating, and plan to revisit it closer to the first readout.

Read the full article here