COP28 is underway in the United Arab Emirates and you can expect lots of what Greta Thunberg calls ‘blah, blah, blah.’ The media will focus on non-issues such as who is and isn’t attending, delegates’ affiliation (or not) with the fossil fuel industry, which wealthy person will call on others to live simply, and what is being worn on the red carpet. Well, maybe not that last one.

Poor nations will point to the environmental damage inflicted by rich nations, and rich nations will argue that poor nations’ growing greenhouse gas emission are becoming dominant. (Both true.) Pledges of financial support and goals and targets will flow like water at Niagara Falls, but real money streams will be more like Death Valley. Liberals will decry climate denialism while conservatives will lambast climate hypocrisy, and Simon Stiell’s use of a quote from Yoda will get more likes than billion dollar promises.

Two stories are particularly telling about the almost uselessness of the COP meetings. First, the rich nations have pledged over $400 million to help poor countries pay for the damage from climate change—after thirty years of trying. Given the proclaimed urgency of climate change and need for dramatic acceleration in action and investment, the glacial progress on this must give pause to policy-makers and activists.

The other report that caused at least one person (okay, it’s me) to roll his eyes is the dispute over whether the final report will call for a ‘phase down’ or a ‘phase out’ of fossil fuels. The latter is a case of the perfect backing out the good, that is, refusing half a loaf when a full loaf cannot be achieved. Aside from the fact that the wording of the conference report will have no effect on the action of emitters (mostly consumers), a total elimination of fossil fuel use

The divide between rich and poor nations will certainly be contentious, with rich nations adopting a ‘don’t do what I did, do what I say’ attitude which will not influence many decision-makers in poor nations. And it’s not just that the rich nations’ are ducking responsibility for past emissions, they show only minimal movement towards the supposed ‘net zero’ goals that have somehow become the holy grail of climate change policy.

For instance, the IEA has noted in its 2020 World Energy Outlook that achieving Net Zero Emissions by 2050 will require many behavioral changes, including making all trips under 3 kilometers on foot or bicycle, reducing speed limits by 7 km/h and revising up (or down) heating (and air conditioning) settings by 3 degrees Celsius. Not only is there lack of movement in that direction in the rich world, but their public seems increasingly unwilling to make sacrifices for global emissions goals. This does not augur well for efforts to convince poor nations to eschew fossil fuel-powered development.

Sadly, the ‘no loaf is better than half a loaf’ attitude will deter efforts to promote economic development with cleaner, not clean, energy. For example, in many places increased used of conventional energy would reduce deforestation, thus cutting greenhouse gas emissions and habitat loss, while improving indoor air quality. But some advocates will oppose promotions of nuclear power (out of ignorance) or fossil fuels like propane or natural-gas fueled power generation because they are absolutist. Poor nations will doubtless be disinclined to listen to those traveling thousands of miles to tell them to eschew economic growth.

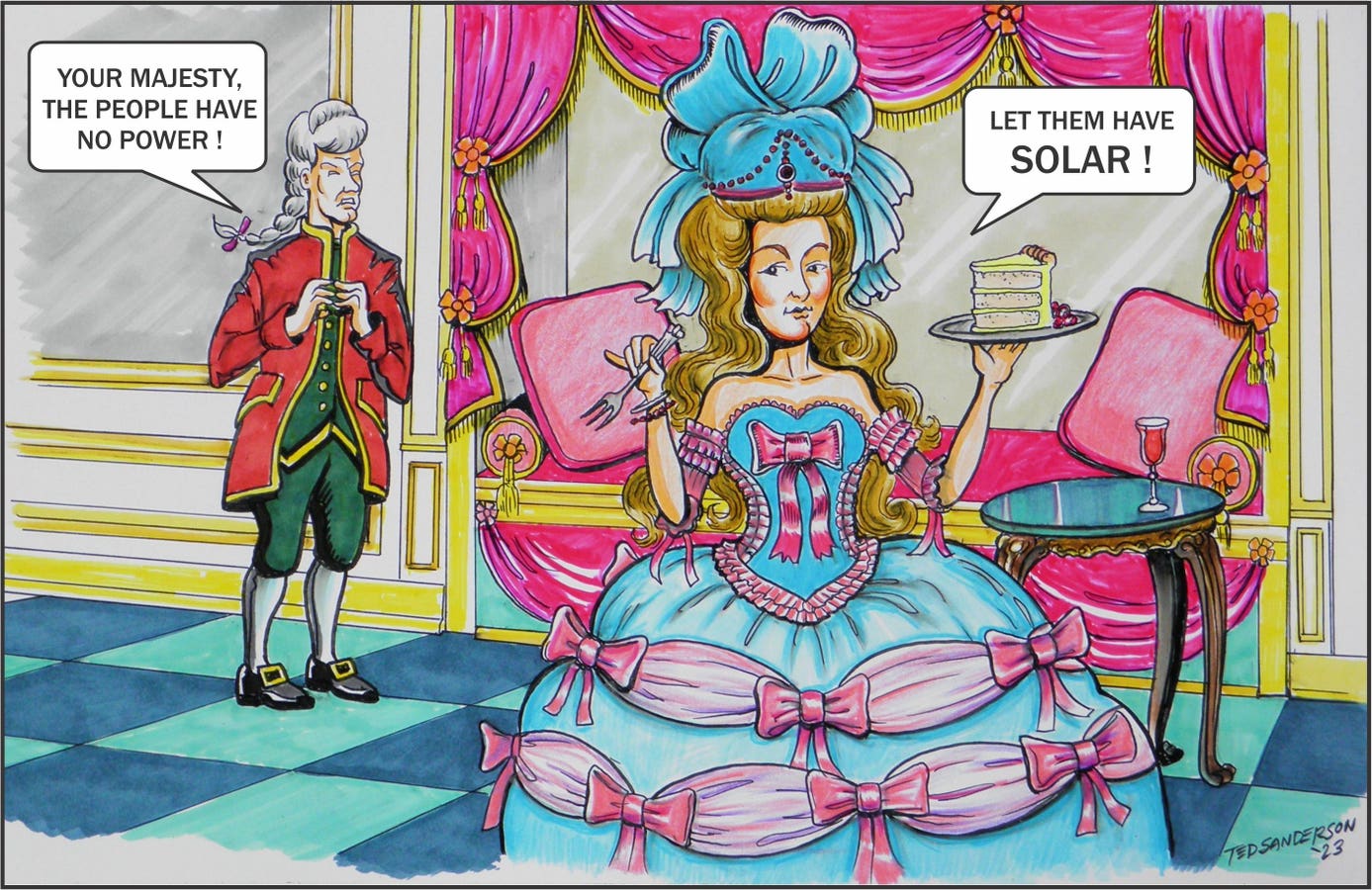

Ultimately, attacks on fossil fuel companies and governments will act as therapy for advocates, but not reduce consumption any more than the ‘war on drugs’ has cut narcotics use around the world. More important, the conflicting goals of alleviating energy poverty and reducing greenhouse gas emissions probably be left unresolved: rich nations will focus on the latter and poor nations the former. The basic truth that economic development requires more energy and that conventional sources are usually more affordable will be swept under the rug with cliches like ‘solar and wind are cheaper than fossil fuels,’ something that is rarely true. Pretending expensive renewable power is the solution is like telling starving people ‘let them eat organic cake.’ An attitude that didn’t work out so well the last time around.

Read the full article here