A marine expedition, including a researcher from the Marshall Islands, have visited Bikini atoll, as part of a scientific voyage across the Pacific Islands.

Bikini atoll was used for peacetime atomic explosions between 1946 and 1958, but since been opened up to diving and sport fishing; as a whole, the biodiversity of the Marshall Islands includes 106 species of birds, 37 mammals, 1059 fishes, 728 crabs, shrimps and other crustaceans, 126 starfishes and 40 sponges.

In a months-long research tour by the Pristine Seas project, an international team of ocean researchers and US-based filmmakers explored the waters of Kiribati, Tongareva, Niue, and the Republic of Marshall Islands.

Collectively, the team traveled 3,500 miles (5,632 kilometers); completed 645 dives; gathered terabytes of film, including footage of Humpback whales with their newly-born calves.

These remote atolls are earmarked by the government for protection and researchers from Pristine Seas are partnering with the local government and regional leaders to find out more about these safe harbours for whales, sharks, turtles and countless fish—as well as birds—with an eye toward protecting them.

One of those local agencies is the Marshall Islands Marine Resources Authority under the Protected Areas Network office (MIMRA–PAN).

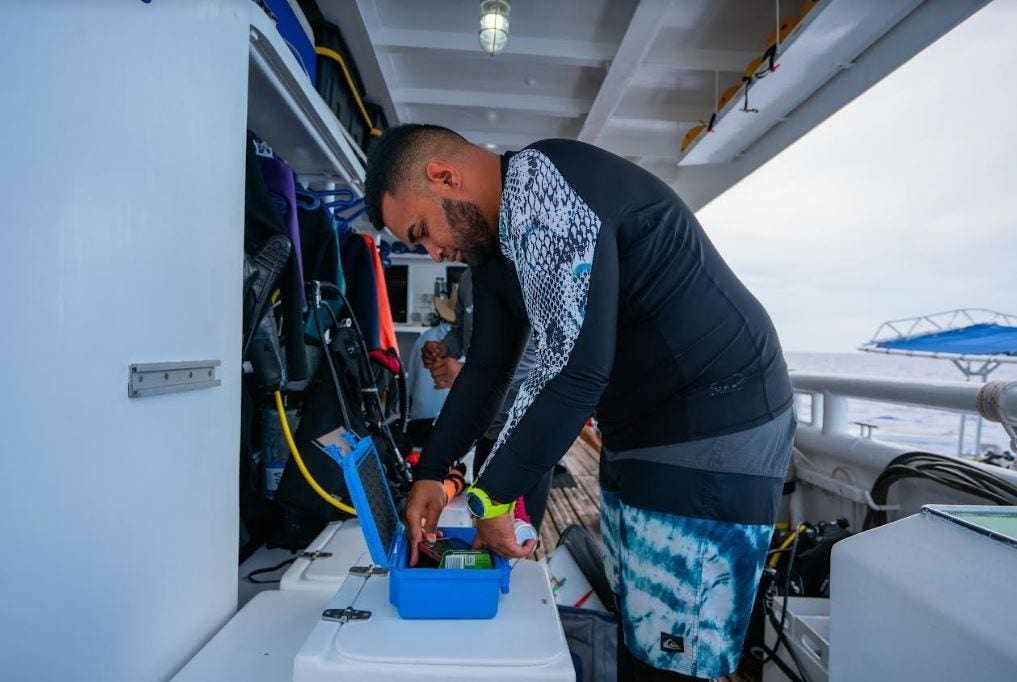

Bryant Jeffery Zebedy, a researcher on the expedition and a MIMRA–PAN officer explains that the aim of the Protected Areas Network office is to help local communities on establishing new areas of protection, assist with monitoring of important natural resources and developing beneficial socioeconomic activities related to protected areas for local communities.

“One of our main goals is to ensure that communities who own protected areas are provided with the best information and tool-kits to manage their resources appropriately,” he says, adding that they provide consultations to help communities have a better understanding of how essential the resources in their areas are.

“The work we do contributes to a broader framework called the Reimaanlok (which means “looking towards the future”) and it ensures that each community in the Marshall Islands gets an atoll profile based on results of assessments that would encourage locals to secure their resource management plans,” Zebedy says.

In June 2023, 193 United Nations members adopted a legally- binding marine biodiversity agreement, with 75 articles aiming to protect, care for, and ensure the responsible use of the marine environment, maintaining the integrity of ocean ecosystems, and conserving the inherent value of marine biological diversity.

Marshall Islands

Zebedy explains that he grew up surrounded by coral reefs just a couple meters away from his doorstep in Majuro, the capital city of the Republic of the Marshall Islands.

“RMI is a nation made up of atolls, which are spread out through the vast ocean: my country is made up of mostly water and limited land, the ocean is our backyard and the main provider for protein,” he says, “It is an instinct to pick up interests in the marine ecosystem given that it has been embedded through ancestry lineage, culture, and just my overall surroundings (geographical features).”

Zebedy explains that he is very proud to be working on projects that help stabilize the well-being of his country’s marine environment.

“Safeguarding our coral reef ecosystems and other marine resources would mean securing culture and identity for those in the future,” he says, “Through this work, I hope that our long-term initiatives in RMI will also contribute to global marine conservation goals.”

Tuna Trends

Another scientist studying climate change impact in the Pacific Ocean is Dr Diva Amon, a scientific researcher at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory at the University of California, Santa Barbara and Director and Founder of NGO SpeSeas.

She explains that climate pressures are expected to push bigeye, skipjack and yellowfin tuna from their current range near small, developing Pacific nations into a “climate refuge” in a deep-ocean zone of the eastern Pacific Ocean.

“These tuna are going to be leaving these Pacific Nations and moving into the high seas and progressively eastward,” she says, adding that the highly-mobile tuna might arrive to these new areas only to find it is already inhospitable due to deep-sea mining.

Amon is the lead author of a paper, published in the journal npj Ocean Sustainability, which focuses on the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean, a maritime region southeast of Hawaii containing 1.1 million square kilometers (or 424,712 square miles, an area 11% of the land area of the United States) of deep-sea mining exploration contracts.

Read the full article here