Larry Ellison’s vision for the future of medicine crystallized for him in a doctor’s office.

Oracle’s billionaire cofounder needed medication to help manage his cholesterol. He said his “very fancy doctor,” a molecular biologist, prescribed a statin called Crestor. The choice was informed by Ellison’s age, sex, ethnicity, and family history. But it was still, Ellison realized, just “a pretty good guess.”

Which got him thinking: What if, instead of guesswork, doctors could lean on generative AI to comb through a patient’s medical records, along with those of millions of other patients? With such a massive database, doctors could spot the warning signs of disease faster, reduce the need for trial and error, and make better-informed decisions about treatment.

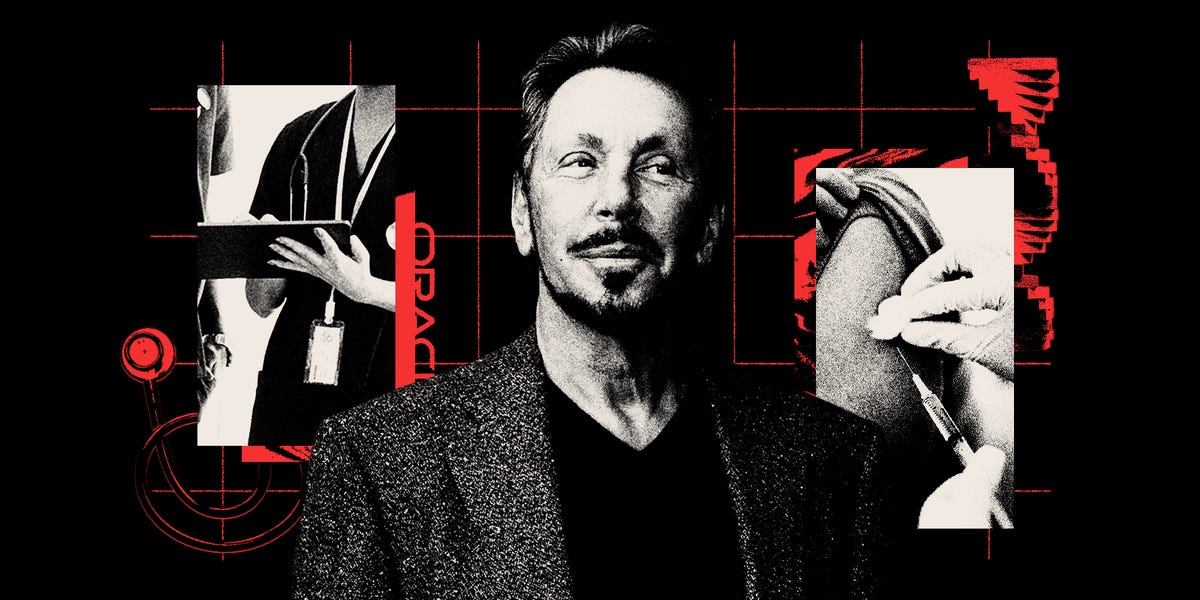

Ellison told this story last fall at Oracle’s CloudWorld conference in Las Vegas. At 79, Ellison cut a trim figure in a black T-shirt, with a visage that hinted at significant investments in antiaging. The moral of the story seemed to be that whatever the world’s fifth-richest person demanded for himself could ultimately benefit everyone.

That was the promise of Cerner, the medical-records company Oracle bought in 2021 for $28.3 billion — Oracle’s biggest acquisition. At the time, Cerner managed the electronic health records for a quarter of all American hospitals, including those run by the Pentagon and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ellison’s plan was to pump all that medical data into Oracle’s AI models and develop an EHR of the future.

“You have this wealth of data that will help doctors make much better decisions of what therapeutics to give you, and that will deliver better outcomes at a much lower cost,” Ellison said onstage in Las Vegas, adding, “I’m not sure there’s anything we’re working on here at Oracle that’s more important than this.”

There was just one problem: Cerner was a total mess. While Ellison was fixated on the wildly exciting possibilities of marrying Cerner’s medical records with Oracle’s technology, Cerner was failing at even the most elementary tasks of data management. The company’s rollout at the VA, which serves 9 million vets, had been a slow-moving catastrophe. One feature of its electronic records system had caused more than 11,000 orders for medical care to disappear into an “unknown queue.” As a result, thousands of patients didn’t receive the treatment their doctors had ordered. VA staffers were left in what one hospital leader called “a constant state of hypervigilance and distress” as they scrambled to retrieve and reenter the missing orders, which wound up harming 149 patients. Even worse, errors in the system’s underlying design were contributing factors in three deaths.

I’m not sure there’s anything we’re working on here at Oracle that’s more important than this.

Larry Ellison

Cerner’s electronic records, in short, were a deadly disaster for the VA. Never mind the futuristic, AI-driven healthcare system Ellison envisioned. In purchasing Cerner, Oracle had saddled itself with a huge liability. The company found itself in a race against time to fix the broken and dysfunctional system it had inherited from Cerner — before more veterans were injured or killed.

Ellison first approached Cerner about an acquisition two decades ago.

It was the mid-2000s, and the healthtech sector was red hot. The RAND Corporation had released a report estimating that the mass digitization of medical records would cut healthcare costs by $81 billion a year. While some saw the prediction as excessively rosy — it was paid for, in part, by Cerner — the report helped pave the way for a massive infusion of federal stimulus dollars to supercharge the adoption of electronic health records at American hospitals. Never mind that EHRs were more cumbersome than advertised; RAND would later conclude there were barely any savings. The promise of bringing hospitals into the digital age was deemed too important to put off.

Meanwhile, Big Tech was starting to invest heavily in healthcare IT, and Oracle wanted in.

Neal Patterson, Cerner’s cofounder and its CEO at the time, was not impressed with Ellison’s pitch. Like other executives at the company, he was distrustful of Silicon Valley. Big Tech, they felt, brought more chutzpah than expertise to the healthcare table. For years executives at Cerner passed around an internal slide that cataloged tech investments in healthcare and the raft of embarrassing exits by companies like GE and Siemens. Patterson rebuffed Ellison’s advances, according to a former Cerner executive familiar with the discussions.

A decade later, Cerner scored a huge win. In 2015, it beat out Epic, its main competitor, for a $4.3 billion contract to handle electronic health records for the Defense Department. Two years later, it landed a similar contract for the VA, worth an estimated $10 billion, without even having to bid. The thinking was that giving both contracts to a single company would ensure seamless care for service members, especially in the period immediately after they’re discharged, when they’re most vulnerable to mental illnesses and substance-use disorders. “I wanted to move towards a single instance of an electronic record with the Department of Defense to make sure that this issue was resolved finally, once and for all,” says Dr. David Shulkin, who served as the secretary of veterans affairs at the time.

But Cerner didn’t have long to savor its victory. A month after it landed the VA contract, Patterson died of cancer. A bruising succession process ensued. Cerner was losing ground to Epic, and its stock had plateaued. In 2019, the activist investor and private-equity shop Starboard Value gained seats on Cerner’s board, putting public pressure on the company to turn things around.

What’s more, taking on two vast government systems turned out to be overwhelming. In the fall of 2020, as Cerner’s inaugural system was rolled out at the VA health center in Spokane, Washington, things began to go wrong. Doctors and nurses complained that the system was slow and difficult to use, requiring them to spend more time inputting data and less time caring for patients. “You’re spending all your time messing around on Cerner and taking like 10 minutes with your patients,” one VA provider says. While VistA, the bespoke EHR that Cerner had replaced, was outdated and vulnerable to cyberattacks, it was generally reliable and user-friendly. With the new system, completing basic tasks was maddeningly complex, impeding the care Cerner was designed to streamline.

As records disappeared into Cerner’s unknown queue, patients with serious illnesses went untreated. In one instance, a scathing report by the VA’s inspector general said, a provider entered an order for a homeless patient at risk of suicide to receive follow-up care, but the order never went through, and the patient later had to be hospitalized after threatening to kill himself.

The unknown queue had been designed to capture orders Cerner couldn’t deliver to the intended location. But the system didn’t send an alert when this happened, and the inspector general found that Cerner had failed to train VA staff on the feature, putting the burden on the VA to identify the issue and request a fix. One VA leader compared Cerner’s attitude about the missing medical orders to the post office stuffing “undeliverable mail behind a bush instead of placing them back in your mailbox.”

While the VA had promised to “do right by both veterans and taxpayers,” the switch to Cerner was doing harm. One Spokane veteran, Charlie Bourg, blames Cerner for a delay in getting a prostate-cancer diagnosis, after a referral was diverted into the unknown queue. By the time the mistake was discovered, Bourg’s cancer had spread to the lymph nodes between his spine and stomach, and it was too late to do anything about it. The cancer was terminal. “I never gave the VA permission to gamble with my life,” Bourg says.

As Cerner was rolled out to more VA and Defense Department health centers, their shared activity and data — more than Cerner had ever handled at once — pushed the company’s aging hardware to a breaking point. And since its system wasn’t on the cloud, Cerner was struggling to meet the increasing demand. It had agreed to process tens of millions of crucial medical records, but it couldn’t handle the subsequent deluge of data.

The longer Cerner’s system ran, the more the problems piled up. By the time Oracle approached the company for the second time, Cerner was no longer in a position to say no.

IIn the years after Ellison first approached Cerner, he became preoccupied with matters of health and longevity. “Larry and I both share a sadness with all the folks we’ve lost to cancer,” says Marc Benioff, the Salesforce CEO and longtime Ellison protégé. “He wants to extend human life and help people live healthier lives. He’s quite advanced in age, and aging, and may not be able to benefit himself.”

Medicine has been a lifelong obsession for Ellison. He once thought of becoming a doctor, but he didn’t stick with school long enough to get a degree, much less a medical degree. Once he became wealthy, he started to view death, as his biographer Mike Wilson put it, as “just another kind of corporate opponent he can outfox.”

Ellison views healthcare as “a remarkably backward business,” says Dr. David Agus, a renowned oncologist who met Ellison in the mid-2000s, right around the time Oracle first approached Cerner. Agus was treating Ellison’s nephew for prostate cancer, and he’d later treat the Apple cofounder Steve Jobs, Ellison’s close friend, who died in 2011. Since then, Agus and Ellison have collaborated on healthcare investments worth hundreds of millions of dollars, including the Ellison Institute of Technology and Sensei, a wellness-retreat company that includes a health utopia built on the Hawaiian island Ellison owns almost in its entirety.

“We’ve met with hospital administrators, researchers, and doctors,” Agus says. “He commits to them, ‘I can solve this problem.’ And he does. Larry actually solves the problem, not just gives money.”

Ellison saw medical records as another area where he could solve a problem. EHRs stand at the center of modern healthcare, used for storing a patient’s medical information, ordering follow-up appointments, calling in prescriptions, and more. And yet the systems are treated mostly, as Ellison likes to say, as a “bag of words” — you can’t easily extract data from them on a mass scale. All that medical information was going to waste.

Epic may have been a more obvious target for Oracle, since it had a larger share of the market and dominated among large hospitals and research facilities. But Cerner, the go-to EHR for small and midsize hospitals, had a quality that would have appealed to Ellison: It was widely seen as taking a more relaxed approach to data privacy. The company was investing in the technology infrastructure to help hospitals share data with one another — and with third parties.

As it happens, the pandemic strengthened Oracle’s case for scooping up Cerner. In the race to defeat the coronavirus, both companies were afforded greater latitude in handling patient records, including those that fall under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. That would enable Oracle to get started on Ellison’s EHR of the future right away. Buying Cerner would also help the tech giant compete with Amazon and Microsoft in the massively profitable cloud-computing business and establish a foothold in the healthcare industry, which, at $4.4 trillion, accounted for roughly 18% of the American economy in 2022. It seemed like nothing but upside for Oracle.

Oracle and Cerner announced the deal in December 2021, and the acquisition was finalized on June 8, 2022. Oracle believed it was finally in a position to fulfill Ellison’s dream of revolutionizing modern medicine. In reality, it had acquired a high-tech filing system that couldn’t even perform the simplest of filing tasks.

The stark reality of what Oracle had just paid for was made clear six weeks after the deal closed, when the tech giant was summoned to Washington, DC, for a grilling before the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs.

In the months since Oracle had announced its intention to buy Cerner, the mess at the VA had only gotten worse. Outages were increasingly common, and one Cerner executive says the entire system was on the verge of failing: “We were going to go off a cliff and die.” The system was considered so dangerous that its rollout to the remaining 166 VA medical centers had been put on hold. Senators listed 36 fixes they expected Cerner — now Oracle — to address before additional sites could make the switch.

Oracle, incredibly, claimed it hadn’t been aware of the magnitude of the challenges facing Cerner when it made the biggest acquisition in its history. “I would say there’s always things that you discover after the fact,” Mike Sicilia, the Oracle executive leading Cerner, told the irate lawmakers. “You know, we certainly had read the press, and we certainly had read things that were publicly disclosed. But there’s nothing like owning something to fully understand what’s going on.”

Still, Sicilia assured lawmakers that Oracle intended to turn things around. The company, he said, had already shifted its top talent, including senior engineers, to work on the VA project. Within nine months, Oracle would move the project onto the cloud, remedying bugs and cutting costs. It would also design a state-of-the-art program for pharmacy, a trouble-ridden area for the project. “Everything here is fixable and addressable” and Cerner would soon be the “gold standard” among EHRs, Sicilia said, adding, “We intend to exceed expectations.”

Oracle, incredibly, claimed it hadn’t been aware of the magnitude of the challenges facing Cerner when it made the biggest acquisition in its history.

Behind the scenes, Oracle was throwing resources at the situation. To address the raft of blackouts and slowdowns, Oracle installed expensive new hardware and made tweaks that stabilized the system and reduced outages dramatically, the Cerner executive told BI. Ellison was directly involved, holding a monthly meeting with 50 or 60 executive and senior vice presidents in the Oracle Health unit to review incidents and brainstorm solutions, according to a high-level employee who attended the meetings. “Oracle is still learning what they have actually acquired from Cerner,” an Oracle executive concedes.

But as Sicilia was trying to assuage concerns on Capitol Hill, a fresh disaster was unfolding at the VA. Only this time, it was happening on Oracle’s watch.

Anthony Jones Jr., a 28-year-old Ohio native who had served in the Navy for four years, had a history of post-traumatic stress disorder and suicide attempts. In May 2022, he was due to see a VA psychologist, but he failed to show up.

At the time, the Columbus VA had just switched over to Cerner. One feature of the EHR was that if a vet missed an appointment, the no-show would trigger VA staff to follow up. For mental-health cases, VA rules require that vets get three calls, on separate days, followed by a letter. The extra layer of precaution is vital because vets are far more likely to die from suicide or a drug overdose than nonveterans. But because of a design error, that didn’t happen. In Jones’ case, the record of the no-show “just kind of evaporated,” says a Columbus provider familiar with his care. Jones got two calls, but not a third.

Six weeks later, on July 4, Jones was found unresponsive in the shower with the water running. The coroner’s report noted that numerous empty cans of inhalants were found scattered around the apartment.

By the time of Jones’ death, Oracle was fully in charge of the electronic records system — but it didn’t discover and fix the error until August. This led to the VA sending out 70,000 letters to veterans who might have been affected by the error, including 24,000 in central Ohio alone, according to a letter to lawmakers from Donald Remy, the VA’s deputy secretary at the time — a copy of which was obtained by BI.

The VA’s inspector general later issued a report on the scheduling error that described a case mirroring Jones’. It concluded that “the lack of contact efforts may have contributed to the patient’s disengagement from mental health treatment and ultimately the patient’s substance use relapse and death.”

In another case linked to the same scheduling error, a vet with cirrhosis of the liver failed to appear for an appointment with staff to discuss his drinking, according to a provider familiar with his care. When the vet didn’t show up, VA staff — unaware of the scheduling error — left a single voicemail. The vet died in late August of complications from liver damage.

The vet’s disease was already so progressed that it’s unlikely a single appointment could have made the difference. But because of Oracle’s oversight, there’s no way to know if better follow-up could have saved the veteran’s life.

“Could you imagine in a case like that where we did all the outreach we could have — but that one call,” the VA provider says. “And then having to tell that family member he should have got one more call.”

A month later, there was another death in Columbus, this time linked to an error in Cerner’s pharmacy app. Antibiotics ordered for a vet who had been treated in a community hospital didn’t arrive. When the vet’s family called the VA pharmacy to see what was holding it up, they were given a tracking number — confirming, it seemed, that the medication had been shipped. But according to Remy’s letter to lawmakers, the Cerner EHR had generated a bogus tracking number; the medication had been slated for pickup. The vet never received the medication, and his condition worsened while at home. He died of hypoxia in late September.

Problems with ordering medications were widespread. When Cerner was first deployed in Columbus, delays kept patients with severe schizophrenia waiting for their medication, a Columbus provider says. In the old system, ordering the shots they needed took about two minutes. It required 30 or so steps — and making a single mistake meant starting over. Vulnerable patients, already resistant to treatment and prone to stress, were kept waiting. In one case, staffers had to retrieve a patient who’d bolted for the parking lot bus stop. “By the time we go through all of this difficulty of ordering the medication — which should be a simple thing — the patient can’t hardly take it and they go running outside,” the provider says.

After Oracle took over, it took months for improvements to be made — and the orders still take 10 minutes to complete.

Nearly two years after its blockbuster deal with Cerner, Oracle says it has made thousands of improvements. “Our veterans and the people who care for them deserve a world-class EHR system,” Seema Verma, the head of Oracle Health and Life Sciences, said in a statement to BI, “and Oracle is delivering it.”

The VA also insists it is addressing the problem. “We know from listening to both veterans and VA clinicians that the electronic health record is not meeting expectations — and we’re holding Oracle Health and ourselves accountable to get this right,” says Dr. Neil Evans, who heads the VA’s EHR modernization office. The rollout of the system remains on pause, and the VA will impose higher penalties on Oracle if the company fails to meet performance targets.

But Oracle is still struggling to stabilize the system it bought. The company hasn’t fully moved Cerner onto the cloud, as Sicilia promised. While outages have decreased, the VA says they remain “an area of significant attention.” According to one Columbus provider, the system went down for 90 minutes in late April, forcing staff to write notes by hand. “Ninety minutes is an eon in clinical time,” the provider says. “No scheduling, charting, ordering, reading — nothing.”

And while Oracle said it largely resolved the issues with the unknown queue within months of buying Cerner, two VA clinicians described a case from last fall where the disappearance of lab results caused a delay in a patient receiving critical medication. The records, they suspect, went into the unknown queue.

Ellison continues to push for his EHR of the future. But one Oracle executive described the VA contract as a “shackle,” absorbing time and attention from Ellison’s grander vision for the database he spent so much to purchase. And while Ellison is pushing the AI envelope, there’s a chance Oracle could lose a lot of the health data that made Cerner such an attractive bet in the first place. Cerner has continued to lose ground to Epic, its main competitor. Intermountain Health and UPMC, two massive longtime Cerner clients, recently announced they were switching to Epic.

EHR deployments can cost hundreds of millions of dollars and require extensive training, making hospitals reluctant to bet on a company struggling to get the job done. “Folks feel like Cerner is circling the drain,” says Sara Vaezy, a chief strategy and digital officer at Providence, a health system in Washington with more than 50 hospitals. “You don’t want to pick a dud that you’re going to have to replatform in a few years because they don’t exist anymore or their product is so bad.”

One Oracle executive, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, acknowledged that many of Cerner’s clients were unhappy, in part because cuts to Cerner’s workforce had left them with less day-to-day support. “There’s not a whole lot we have to tell clients other than please hang in there,” he says.

A growing chorus of lawmakers has been calling for the contract to be scrapped. “It’s a political and governmentwide failure,” says Ed Meagher, a former top official at the VA. “The DOD made a terrible decision, and then that forced a terrible decision on the VA.”

It’s clear that shifting a vast government-run system like the VA over to a standard EHR designed for the private sector proved far more complex than either Cerner or the VA anticipated. The EHR that Cerner replaced, VistA, was built specifically for the VA, and it was constantly tweaked and upgraded to suit the needs of individual providers and hospitals. The VA brought this mentality to the Cerner project, flooding the company with requests for special customizations — and Oracle has grown so frustrated that it has stopped taking on individual requests that haven’t been formally contracted.

Within Oracle’s health team, morale has suffered. “Morale is at an all-time low,” an Oracle-Cerner manager says. “We have so much important work to do. Everybody’s velocity is lower because basically everybody is depressed or upset.”

In Spokane, where Cerner was unveiled, it’s not clear that things have gotten any better since Oracle took over. During a recent visit to the VA, Charlie Bourg — the vet whose referral was lost in the unknown queue — noticed that the computer was down and that his providers from different departments seemed to have trouble communicating about his case. “I had to watch them struggle,” he says.

Bourg knew the issues to be on the lookout for. He and another vet, Charlie Monroe, have become something of a rapid-response team for vets in Spokane and elsewhere. Known to providers and patients as “the Charlies,” Bourg and Monroe are among the first to know when a new problem with Cerner is discovered. Lawmakers call them to find out what’s going on. Relatives call when they need help advocating for a patient. “People come up to us out of the blue,” Monroe says. “They know who we are. ‘Can you do something about this? Can you talk to somebody about this?’ No. Yeah. Maybe.”

In February, the Charlies helped connect the family of a recently deceased vet with Rep. Cathy McMorris Rodgers, a congresswoman representing Spokane who has called for the termination of the VA’s contract with Cerner. Based on initial information from the VA, the vet’s daughter was concerned that Cerner might have led to his being given the wrong antibiotic, contributing to his death from sepsis.

Bourg and Monroe are about as different as two vets with long white hair could be. Bourg is soft-spoken and has a flat delivery, even when the topic turns to how much time he has left and how much he worries about his wife and grandkids. (Last December he sued the VA and Oracle for an undisclosed amount.) Monroe, who wears the yellow logo of the Seabees, the Navy’s construction regiment, is loud and likes to say he’s the better-looking of the two. “We’re just two veterans that got involved with this shit because we were screwed over,” Monroe says.

When Oracle entered the picture, the Charlies were confused by the company’s name, believing it to be a video-game company. They don’t know much about Ellison’s grand vision for revolutionizing medicine. They just want vets to get the high-quality care they deserve.

Late last year, not long after Ellison’s appearance at CloudWorld, the Charlies received a surprise invitation to meet with the VA’s leadership in Spokane. Bourg says meetings like that take a toll on his body and mind. Back in 2022, the two had traveled to Washington to meet with lawmakers only to return feeling like it had been a waste of time. “I was totally mentally and physically exhausted,” Bourg recalled, “and it still didn’t do anything.”

Bourg expected to come out of the Spokane meeting feeling the same way. Instead, he delivered a simple message to the assembled leaders. Given Oracle’s track record of botched care, he said, there’s only one thing for the VA to do: put an end to a contract that has proved so disastrous for so many veterans before someone else gets hurt.

“If they aren’t telling me they are shutting it down,” Bourg said, “there’s nothing to say.”

Ashley Stewart is a chief technology correspondent at Business Insider.

Blake Dodge is a correspondent at Business Insider covering technology in healthcare.

Read the full article here