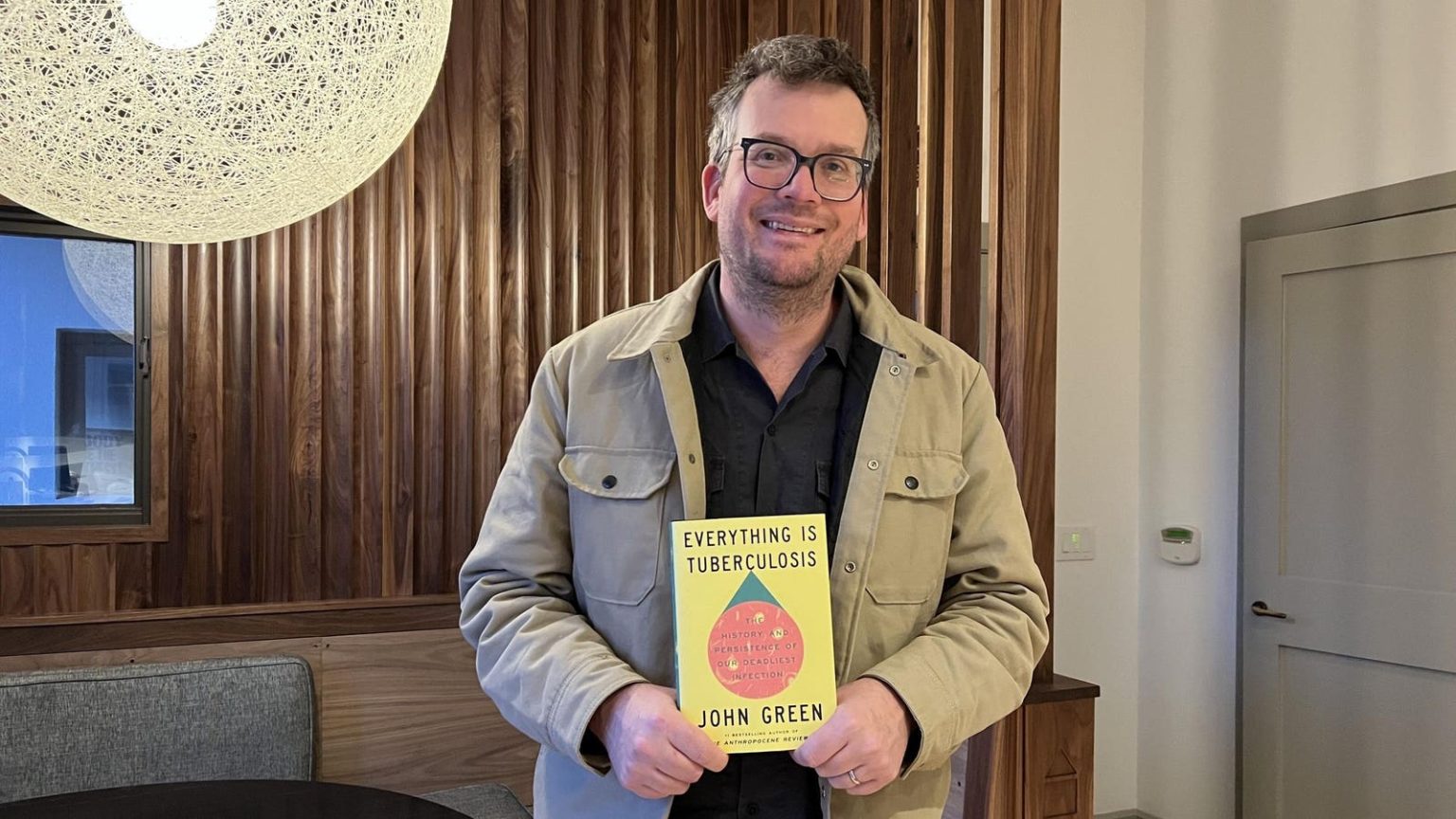

John Green, author of best-selling books including The Fault in Our Stars, could have done anything. He could have written yet another young adult book, or made a new film. But he chose to write a new book on tuberculosis (TB)! Everything Is Tuberculosis is releasing on 18th March, a few days ahead of World Tuberculosis Day.

As a tuberculosis researcher, I am deeply aware of what this devastating disease has done to humankind, and why it kills over a million people every year, even today. But, initially, I struggled to understand why John Green would care about this ancient ‘white plague’ that has likely killed over a billion people in the past couple of centuries.

Spending some time with John at a Partners in Health (PIH) event last fall, I started to better understand why the man cares about TB, and why he has become such a powerful advocate for a disease that gets little attention. My interview with him offers deeper insights into John’s obsession with TB. You have to, of course, read his book to get the full story!

Madhukar Pai: John, you have written several best-selling novels and have reached millions of young adults worldwide. You could have stuck to that successful genre. What made you write a book on tuberculosis? After all, you live in the United States, and your risk of getting TB is very low. Why do you care about TB?

John Green: I wrote a nonfiction book before this called The Anthropocene Reviewed, but this is my first crack at writing about illness and disease in a nonfiction format. Disease has long interested me as a subject for literature because as Virginia Woolf wrote, it is “strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love, battle, and jealousy among the prime themes of literature.” After all, it’s a universal experience–and one responsible for over 90% of human deaths. I’m especially fascinated by tuberculosis because it is so obviously and so painfully a disease of injustice. TB kills 1,250,000 people every year even though it’s been curable since the 1950s. That’s a tremendous failure of our resource distribution systems.

Madhukar Pai: In your book, you do a wonderful job of tracing the history of TB, and its ongoing impact on people even today. Currently, TB is the biggest infectious killer of people, and things might get even worse with the new U.S. government’s attack on humanitarian aid, science, and global health (which I covered in an earlier post). You write in your book “We know how to live in a world without TB. But we choose not to live in that world.” Can you please explain this for the readers?

John Green: We know how to eliminate tuberculosis from communities. We know that comprehensive response–where we actively search for cases, treat every sick person we find, and offer preventive therapy to their close contacts–can reliably end chains of transmission. We have better tools (e.g. molecular tests) and shorter medication regimens than ever before. TB is curable and preventable. We have the tools to end TB, but we are not allocating the appropriate resources to the fight.

Madhukar Pai: Your great-uncle died of tuberculosis in the 1930s in the US. My maternal grandfather died of TB in the 1940s in India. Neither of them had a fighting chance those days, since no cure was available. But today, we have excellent rapid molecular tests, we can quickly check for drug-resistance, and we have short, effective drug combinations. Even drug-resistant TB can now be cured with 6 months of oral medications. And yet, as you put it, paraphrasing Ugandan AIDS researcher and physician Peter Mugyenyi, TB cure is where the disease is not, and TB disease is where the cure is not. What can we do about this problem and make sure everyone has the best tools we have to detect, prevent and cure TB?

John Green: We have to get the cure to the disease, which is not easy or straightforward but is possible. We need to get the cure to rural areas of Lesotho where people are dying needlessly of TB for want of medications that we first synthesized many decades ago. And we need to do a much better job of screening and active case-finding so we’re not identifying TB only when it is extremely advanced. In short, to fight our oldest pandemic, we need to treat it like we would any other pandemic, rather than minimizing and dismissing it because it mostly affects the poor or people in the Global South.

Madhukar Pai: You are more than a book author. You are an advocate for TB. You are using your megaphone to call out the injustices in access to tools. You worked hard with advocacy groups and Nerdfighteria to reduce the price of a rapid molecular test by Cepheid (Danaher), and to make bedaquiline drug (by J&J) more accessible. What made you translate your words into concrete action? Who inspires you to be an advocate?

John Green: I am inspired by my fellow TB fighters, and especially by those who paved the way for me, like Shreya Tripathi, a young woman from India who died of TB amidst a years-long battle with Indian courts to be able to access the anti-TB medication bedaquiline. Shreya died because the world is unjust, and while I would’ve received bedaquiline with no problem, she had to fight for it until just before her death.

Madhukar Pai: Our mutual friend, the late Dr Paul Farmer, showed the world that we can offer quality TB care even in countries with limited resources. How did Paul influence your thinking about TB and global health in general? What lessons of his do you remember the most?

John Green: Paul influenced every aspect of my life, from the way I think about marriage to the way I think about work to my passion for global health equity. He inspired me and so many others to expand our imagination of what might be possible. Paul helped me to understand that TB and other diseases of injustice are not really caused by bacteria or other pathogens. They are really caused by human-built systems, which means they can also be cured by reforming and reimagining human-built systems.

Madhukar Pai: In a recent interview in Vox, you spoke about wanting to make the ‘world suck less.’ I love it and use that as a tag line for teaching why global health matters and my students love it! Beyond the TB crisis, the world is now facing many challenges, including climate crisis, pandemics, conflicts, widening economic inequities, and right-wing, autocratic, leaders who are undermining years of progress. How do we stay hopeful in this era of polycrisis and fading democracy? What advice would you have for young people who look up to you?

John Green: I think hope is the correct response to the miracle of human consciousness. I am extremely concerned (and discouraged) in the face of our historical moment. But I refuse to respond with despair. The year I graduated from high school, 1995, over twelve million children died before the age of five. Last year, fewer than five million kids died. As you note, that progress is currently being undermined–and that’s catastrophic. But we can look to that progress in hope. There is nothing natural or inevitable about the world reducing child mortality by 60% in 25 years. That happened because of millions of people working together in the messy, complex, often unseen labor of building and maintaining better healthcare systems. Those builders and maintainers are the people who give me hope.

Madhukar Pai: Thank you, John, for your incredible global health work, philanthropy, and your passion for making the world suck less. You are breathing new life into TB and global health advocacy, and we need it now, more than ever before. Paul Farmer would have called you an antidote to despair.

Read the full article here