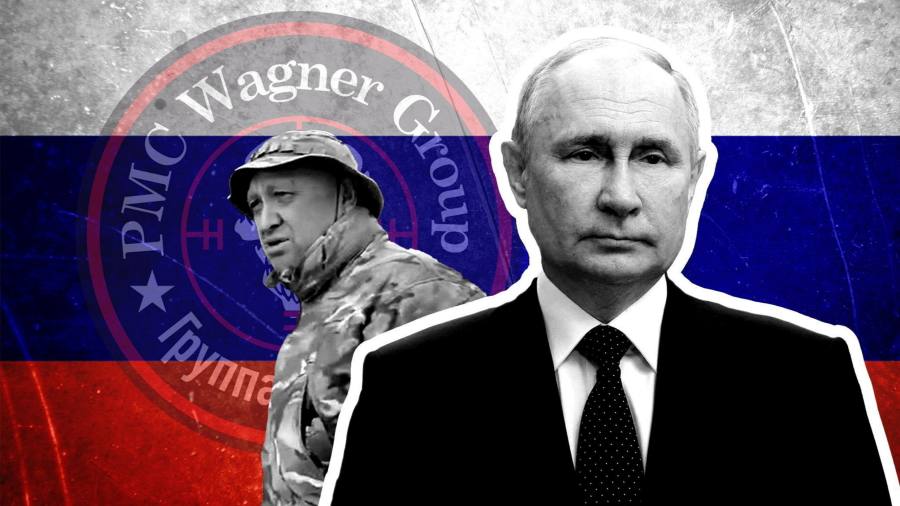

Vladimir Putin vowed to punish Yevgeny Prigozhin for “treason” over the warlord’s armed uprising. Instead, the former Kremlin caterer and his Wagner group have got off all but scot free after launching the first coup attempt in Russia for three decades.

Prigozhin’s failed putsch ended abruptly, but it still exposed deep flaws at the heart of Putin’s regime, called his invasion of Ukraine into serious doubt, and raised the spectre of state collapse if unrest were to boil over again, people close to the Kremlin told the Financial Times.

“It’s a huge humiliation for Putin, of course. That’s obvious,” said a Russian oligarch who has known the Russian president since the 1990s. “Thousands of people without any resistance are going from Rostov almost to Moscow, and nobody can do anything. Then [Putin] announced they would be punished, and they were not. That’s definitely a sign of weakness.”

At the root of the rebellion lay frustration within Russia’s armed forces at how Putin had been handling the full-scale invasion of Ukraine — to the extent that a row between paramilitaries and regular armed forces nearly brought down the state. Russia’s army and security services were unable to forestall Prigozhin’s revolt.

The ease with which Wagner launched its revolt, the lack of resistance it met from other security forces, and the rapturous reception its fighters met in the southern city of Rostov as they stood down “damages [Putin’s] reputation domestically”, said Alexei Venediktov, the well-connected former editor of the Ekho Moskvy radio station.

“It turns out you can start a revolt against the president, and be forgiven. That means the president isn’t that strong.”

The extraordinary events have led even ardent supporters of the invasion to publicly question Russia’s rationale for it and worry further shocks could follow.

“The whole world has seen that Russia is on the verge of a dire political crisis,” Sergei Markov, a former Kremlin spin-doctor and MP, wrote on Telegram. “Yes, the putsch didn’t succeed, but putsches have fundamental reasons behind them. And if those reasons remain, then the putsch might happen again. And it could be successful.”

For now, the Kremlin says it has quelled the threat from Prigozhin after the warlord agreed to leave Russia for Belarus in exchange for a promise not to prosecute him or Wagner’s fighters.

On Sunday, Russian state media attempted to show life going on largely as normal. Municipal workers fanned out to repair the highways damaged by Wagner’s advance, while Russian forces reclaimed the command centre in Rostov that Wagner had briefly taken over the day before.

But Russia’s attempt to play down the incident as an inconvenient blip belies the deep problems the invasion of Ukraine has created for Putin’s rule.

“You can’t see this as anything other than a sign of weakness and dysfunction,” said Ekaterina Schulmann, a Russian political scientist. “This isn’t some kind of unexpected one-off event or external shock. This is part and parcel of the war,” she said.

The Kremlin insisted on Saturday that Prigozhin’s revolt would have no effect on its handling of the war. But Wagner’s prominent role on the front lines was itself a consequence of how Russia mishandled the invasion.

Initially formed to fight covertly in conflicts around the world, Putin redeployed Wagner’s men to Ukraine when the invasion plan failed. He then let Prigozhin swell his ranks by personally signing pardons for convicted criminals who joined up to fight.

“They started a war they shouldn’t have, they couldn’t run it properly, and they decided to resort to extremes by letting him round up an army of prisoners,” Schulmann said. “He became a political actor, and they had to deal with it. One thing leads to another.”

Putin’s reluctance to end Prigozhin’s months-long public feud with the defence ministry appears to have convinced the former caterer he was powerful enough to succeed in his mutiny attempt, according to people close to the Kremlin.

But the episode has also proved damaging for Prigozhin after he failed to secure the resignations of defence minister Sergei Shoigu or Valery Gerasimov, commander of Russia’s invasion forces.

Some of Wagner’s troops will sign contracts with the defence ministry, the Kremlin said. That amounts to a humiliation after Prigozhin said his group would never submit themselves to Shoigu — a step that would rob him of the money and influence that came from only answering to Putin personally.

Once the revolt began, Prigozhin appears to have had little idea of how to see it through successfully, according to a person who has known the warlord since the early 1990s.

“I don’t think he had anything particular in mind. He just decided to go and convince Putin that he should get to keep all the money they took away from him,” the person said. “Then the situation got completely out of control.”

“At some point he realised he didn’t know what to do next. You get to Moscow, and then what? You open the doors of a dozen prisons, some unimaginable freaks come out, the country goes to shit, and then you get to the Kremlin . . . and you don’t know what to do.”

The humiliating episode will probably prompt Putin to dismantle Wagner and ensure it can no longer threaten the state, said Alexander Gabuev, director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

“They promised not to touch anyone, but I think it’s entirely possible someone will get jailed, or die in mysterious circumstances, to scare the rest,” Gabuev said. “Putin must by now have realised how vulnerable the system is and will try to fix it.”

Much remains unclear about how exactly Russia convinced Prigozhin to stand down, with many in the Russian elite suspecting that Belarus president Alexander Lukashenko, who ostensibly brokered the deal, was a stand-in for powerful figures in Russia.

“Everyone wanted to call [Prigozhin] and make a deal. And in the end they found a more reasonable middleman in the form of Luka, who found a way for both sides to step back,” the person close to Prigozhin said.

After failing to stop the revolt, Russia’s elite is unlikely to escape unscathed either, with Putin now conscious of the threat to his own power. “This was a huge counter-intelligence failure. The CIA knew this was coming, and your own secret services didn’t know or didn’t report it. So he’s going to tighten the screws and keep the elite on edge,” said Gabuev.

But even wholesale changes may not be enough to restore order, the oligarch said. After Russia’s war effort began to falter last year, many in Russia’s elite began discussing the likelihood of a “time of troubles”, a repeat of the long, violent political crisis in the early 17th century when different factions vied for the throne.

But even then, the oligarch said, “if it started I expected the army to intervene immediately. And they did not. That’s a surprise.”

Read the full article here