Republicans who control the North Carolina legislature are moving to change the makeup of state and county election boards and sideline the state’s Democratic governor, Roy Cooper.

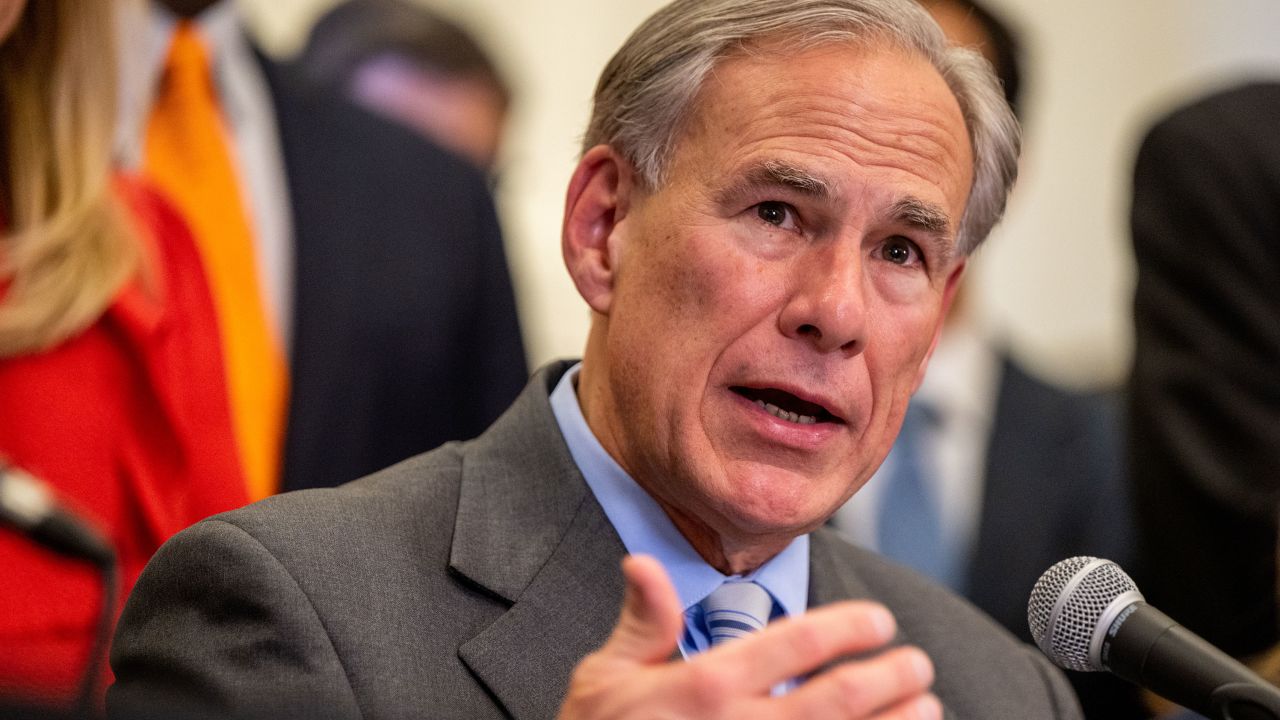

In Texas, GOP Gov. Greg Abbott signed a new law that allows a state official appointed by him to take over election operations in Harris County – home to Houston and the state’s largest Democratic stronghold.

New laws in Georgia – a key presidential battleground state – have changed who serves on local elections boards.

And in Wisconsin – where the winner in four of the past six presidential races has been decided by less than 1 point – questions hang over who will run elections in 2024. The term of the state elections administrator, Meagan Wolfe, ends July 1, and her reappointment is in doubt. Some Republican lawmakers have taken aim at Wolfe over changes to election procedures in 2020, when Joe Biden flipped this swing state. A key vote on her future is expected Tuesday.

In pockets around the country, Republican officials are working to change who oversees elections in ways that critics say could shift the balance of power to their party or lead to partisan stalemates when high-stakes Senate and presidential contests are on the ballot next year.

“The rules that are going to be governing the 2024 elections are really being written right now,” said Megan Bellamy, vice president of law and policy at the Voting Rights Lab, which tracks election legislation. “These state legislators are seeking new powers over election administration, and the ultimate outcome could be greater authority for partisan actors in the process.”

In North Carolina, where Republicans now have a supermajority in the General Assembly and can override Cooper’s veto, a bill that recently passed the state Senate would shift some powers over election administration from the governor to state legislators.

Under Senate Bill 749, the membership of the North Carolina State Board of Elections would grow to eight members, up from the current five – with the Republican and Democratic leaders of the General Assembly getting four appointments each.

Currently, the governor selects the members, and, traditionally, a 3-2 split on the board favors the governor’s party. (The Senate also passed several new election rules, including requiring that absentee ballots must be received by 7:30 p.m. on Election Day to count. Under present law, mail-in ballots received up to three days after the election can be counted as long as they are postmarked by the election date.)

The measure to change the makeup of the state elections board would also empower either the state House speaker or the Senate president pro tempore – positions now held by Republicans – to choose the state board’s chairperson and executive director – if the evenly divided board reaches an impasse and cannot quickly decide who should fill those roles.

“They are pretty much making themselves the referees,” Carol Moreno Cifuentes, the policy and programs manager of elections advocacy group Democracy North Carolina, said of GOP legislative leaders.

Cooper slammed the bill as a “power grab” in a Twitter post. “The last thing our democracy needs is for our elections to be run by people who want to rig them for partisan gain.”

Republican state lawmakers pushing the measure say it will bring bipartisan balance to decision-making around elections. They have accused state election officials of reaching a “collusive settlement” with Democratic litigants to extend the deadline to count absentee ballots during the 2020 election.

“So, far from a power grab, 749 levels the playing field,” state Sen. Paul Newton, a bill sponsor, said during a committee meeting earlier this month. “If you’ve got a split board … the only way you can get changes in election policy or administration is by working together.”

The proposal would also give state lawmakers the power to select members of county election boards and shift the authority for hiring local election directors from those boards to county commissioners. Under current law, county election boards recommend an elections director to the executive director of the state elections board, who makes the final appointment.

The association that represents local election directors opposes that shift and argues that county election boards should retain those appointment powers. Its president Sara LaVere, who oversees elections in Brunswick County, told CNN that the current system has “worked beautifully” in the 17 years she’s been involved in election administration in the state.

LaVere pointed out that local election chiefs also have the responsibility to audit county commissioners’ campaign finance reports and flag potential problems or wrongdoing to state authorities.

If election directors are hired by commissioners themselves, LaVere said, “that could be a conflict, turning in the person who basically holds the key to your job.”

Previous GOP efforts to change the state board’s makeup have been struck down by courts and rejected by voters in a 2018 referendum.

But in addition to holding a veto-proof majority in the legislature, Republicans now have a majority on the North Carolina Supreme Court, raising the prospect they could prevail in future court fights.

North Carolina is one of 17 states where state boards either set election policy or share those duties with the secretary of state, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. In four – Illinois, Indiana, New York and Wisconsin – the state boards have even partisan splits, according to Lata Nott, senior legal counsel for voting rights at the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center.

In Wisconsin, where a six-member state elections commission is evenly divided between Democratic and Republican appointees, a showdown looms over reappointing Wolfe, its respected administrator. The commission is set to vote Tuesday on whether to retain her.

In a state where some Republicans in the GOP-controlled state legislature have advanced unfounded voter fraud conspiracy theories, the elections commission, including Wolfe, has faced anger and scrutiny over its guidance to local election officials in the runup to the 2020 election.

At one point, a local sheriff called for charging commissioners with crimes because they waived a requirement during the pandemic to send poll workers into nursing homes to assist with absentee balloting.

Wolfe has declined interviews, but in a letter sent to local clerks made public earlier this month, she said her role is “at risk” because “enough legislators have fallen prey to false information about my work and the work of this agency.” Over the weekend, Wolfe emphasized in a letter to lawmakers that she does not set election policy but merely implements decisions made by the commissioners, who were themselves selected by the governor and legislators.

If the board votes to retain Wolfe, the state’s GOP-controlled Senate would have to confirm her. State Senate President Chris Kapenga has already said he would oppose her reappointment.

If the job becomes vacant and no one is nominated within 45 days, a GOP-controlled legislative committee can appoint a temporary administrator.

In other states, changes to election administration have already been enacted this year.

In Texas, two newly enacted laws targeting the elections process in Harris County have angered Democrats and voting rights activists, who have accused the state GOP of plotting a “power grab” in an increasingly blue bastion.

One of the measures, SB 1750, eliminates the position of elections administrator in a county with a population of more than 3.5 million people – a criterion met only by Harris County. Under the new law, the elections administrator’s duties will be transferred to the county tax assessor-collector and county clerk. The Harris County elections administrator, a position created in 2020, is appointed by the county’s election commission, which is Democratic-controlled. The county’s current tax assessor-collector and clerk are both Democrats.

But another law would go further. SB 1933 authorizes the Texas secretary of state – an appointee of Republican Gov. Abbott – to “order administrative oversight” of a county elections office if, for instance, a complaint is filed or there’s cause to believe there’s a recurring pattern of problems involving election administration or voter registration. The new law affects any county that has a population of more than 4 million people – which, again, only applies to Harris County.

Both laws will go into effect September 1.

Harris County Attorney Christian Menefee, a Democrat, has argued the two measures are “clearly unconstitutional.”

“(Our) state’s constitution bars lawmakers from passing laws that target one specific city or county, putting their personal vendettas over what’s best for Texans,” Menefee said in a statement.

The Democratic-controlled Harris County Commissioner’s Court has given approval for Menefee to file a lawsuit to challenge the new laws.

In Georgia, new laws spearheaded by the GOP-controlled legislature have changed the composition of county election boards across the state. The laws generally give county commissioners the authority to name members to election boards, stripping political parties of a power they once held.

A 2018 Georgia Supreme Court ruling that found members of the DeKalb County Ethics Board could not be appointed by private entities, such as political parties, drove the new laws.

In a memo, the voting rights group Fair Fight argued that GOP-controlled county commissions have used that ruling as “justification” to shift the balance of power to their party on local elections boards.

But the broadest takeover language in Georgia was included in a sweeping elections law enacted in 2021 – paving the way for a state-appointed administrator to replace local election officials in counties deemed low-performing.

After the measure was signed into law, several Republican state lawmakers sought a performance review of elections in Fulton County, Georgia’s most populous county and a Democratic stronghold that includes much of Atlanta. A June 2020 primary – during the height of the pandemic – had been plagued by long voting lines and complaints that voters had failed to receive their absentee ballots by mail.

And after the general election, former President Donald Trump targeted the county with unfounded claims of widespread voter fraud, following his narrow loss in Georgia, once a reliably red state.

Last week, the state elections board declined to take over Fulton County – ending a nearly two-year-long probe that had sparked fears of potential partisan interference.

In the end, the state board concluded that Fulton County election officials had made significant improvements in their operations since the state-led performance review had begun.

Read the full article here