By Mark Finley

The 2023 edition of the Statistical Review of World Energy (the 72nd annual edition; now under the management of the Energy Institute and its corporate partners) was published this week. This means it’s time for my annual commentary. (And time for my annual disclosure: Before joining the Baker Institute, I led the production of the Review for a dozen years at bp—the Review’s home for its first 71 years—and remain a bp shareholder.)

The Review contains comprehensive, objective global data on every energy form as well as key minerals needed for the energy transition. This note will barely scratch the surface of the fascinating insights contained in the Review: Continued rapid growth of renewable energy and minerals critical for the energy transition—but also continued growth in CO2 emissions, for example. So please have a look at its data and commentary (freely available for download) to explore the world of energy for yourself!

The Review contains annual data through 2022, so it is a backward-looking data set that helps us understand in great detail what has happened in the world of energy. The energy situation last year was especially complex, with the ongoing recovery globally from earlier COVID-related shutdowns; the exceptional situation of China, which experienced renewed shutdowns; and of course, the energy impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and related responses by companies and governments around the world. The Review’s summarydoes a good job of highlighting the turmoil in global energy markets last year, so I want to highlight a only a few additional items.

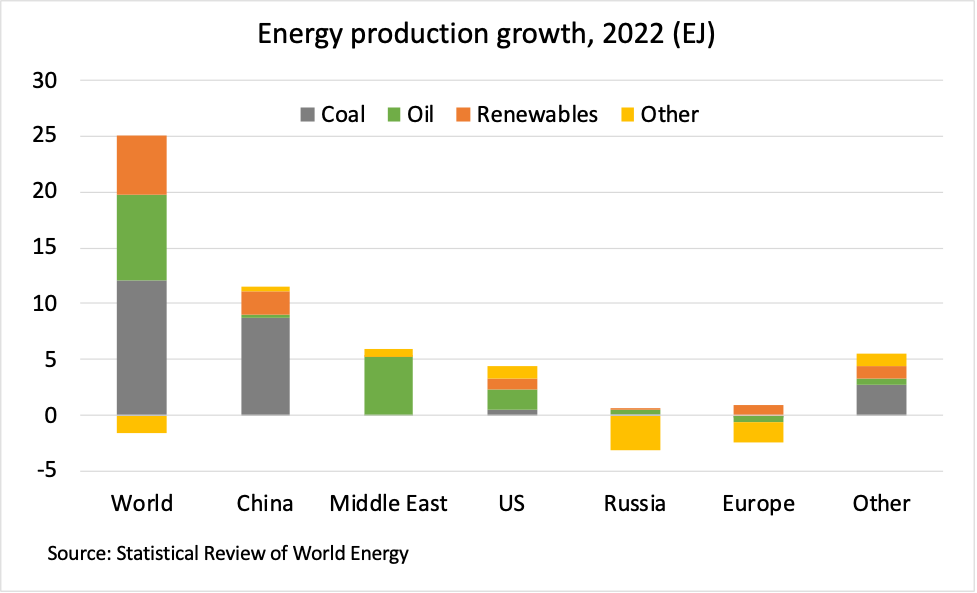

First, global energy production growth significantly out-paced consumption growth.[i] While global energy consumption grew by just 1.1%, slightly below the 10-year average, global production grew by a very strong 4%, nearly three times the 10-year average of 1.3%. The strong growth in energy production was highly concentrated, with China, the US and the Middle East accounting for virtually all of global growth in energy production. Elsewhere, declines in Russian and European production were offset by growth in Latin America and other Asian countries.

China – the world’s largest energy producer and consumer – grew its domestic energy production by a massive 9.1%, more than three times the 10-year average and the strongest annual growth in a decade. China accounted for just under a quarter of global energy production last year, but half of the world’s growth. The largest fuel increase in China by far was coal production, which grew by 10.5% (compared with a 10-year average annual growth of just 1.7%), and accounted for three-quarters of total Chinese energy production growth. Renewable energy grew by 18.1%—this was actually below the historical average growth of nearly 25% but was still strong enough to account for nearly 20% of total Chinese energy production growth.

In the Middle East, production grew by 7.3%, compared with a very weak 10-year average of 0.9%. Nearly all of the growth (90%) came from oil as the region’s OPEC members increased production significantly in the face of recovering global demand and soaring prices. Regional oil production grew by a very strong 9.5%, the strongest growth (in percentage terms) since 1992, and in barrels per day, the 3rd-strongest on record behind only 1973 and 1976.

In the US, total energy production grew by 4.8%, double the 10-year average. Oil and natural gas accounted for two-thirds of the increase, but domestic production of renewable energy and coal also grew robustly.

In Russia, the decline in domestic energy production was entirely due to falling natural gas production, as both domestic consumption and exports to Europe fell sharply. Natural gas output fell by nearly 12%, the largest percentage decline since 2009 and the largest volumetric decline of the post-Soviet era.

And in Europe, regional energy production fell by 3.2%, the largest percentage decline since 2009. The decline was perhaps surprising, given the regional energy crisis provoked by large declines in Russian deliveries of each of the fossil fuels and power shortages despite the continued rapid growth of European renewable energy (+9.4%). Even as North Sea producers Norway and the UK surged natural gas production in the face of soaring prices, regional oil production continued its long-term decline. But the large decline in overall European energy production was driven by exceptional declines in nuclear power and hydroelectricity—both of which saw the largest percentage declines on record (with data going back to 1965). Nuclear power generation fell by 16.3%, driven by maintenance-related outages in France and the policy-driven shutdowns of German plants (although the full closure was delayed until this year). European nuclear output fell to the lowest levels in 40 years. Hydro output (down about 14%) was adversely impacted by drought conditions in many countries.

For me, the other interesting wrinkle (beyond the story lines highlighted by the Review itself) is on global energy trade. Here, the pathways differ significantly by fuel.

For oil, trade expanded strongly along with global production and consumption, rising by 3.4%, well above the 10-year average growth of 2%. Interestingly, trade expanded strongly even though imports in China (the world’s largest importer) fell by 4.5%, compared with average annual growth of over 6% for the past decade.

But more interesting than the overall growth in global trade was the changes in trading relationships driven by the sharp decline in European purchases of Russian oil. Europe reduced its purchases of Russian crude oil by about 15% (while the formal EU embargo didn’t take effect until November, many buyers voluntarily reduced purchases before then).[ii] In place of Russian crude, Europe increased purchases from the US, Latin America and Saudi Arabia; and as has been well-documented, Russia diverted crude shipments to India and to a lesser degree China by offering large price discounts. India, in turn, processed that discounted Russian crude oil and increased its exports of refined products—largely to Europe!

Global natural gas trade saw a large contraction of 5.1%, the largest decline in at least a decade. All of the decline was in pipeline trade, which dropped by a massive 15.5%, almost entirely due to reduced Russian exports, which fell by nearly 40%. Unlike oil, Russia did not have ready access to global markets for its gas—with relatively limited LNG export capacity—so volumes not sold in Europe were largely bottled up in Russia. Globally, LNG deliveries grew by 5.2%, broadly in line with the 10-year trend—but, as with oil, regional flows shifted significantly. Europe increased LNG imports by 58%, absorbing all of the growth in global LNG shipments and diverting cargoes, especially from China and India.

And finally, global coal trade contracted by 3.5% even with increasing consumption and production. Three-quarters of the decline was due to lower Chinese coal imports, which fell by 12.6%, more than offsetting a 10% increase in European coal imports to feed a rare increase in EU consumption.

With a growing focus on energy security—following the successive shocks to the global energy system in recent years—it was interesting to note the evolution of key indicators of self-sufficiency for the world’s biggest energy consumers and producers—China and the US (the 2nd-largest after China on each measure). Chinese imports of oil, natural gas and coal all declined; while domestic consumption of oil and natural gas declined, Chinese coal consumption increased—but production increased even more. (Domestic oil/natural gas production increased as well.) As a result, while China remains the world’s largest net energy importer, the degree of overall self-sufficiency continued its recent trend of improvement—last year domestic energy production was sufficient to meet 87% of domestic consumption, up from about 80% as recently as 2017. Meanwhile, strong domestic production growth (4.8%) improved US energy self-sufficiency by out-pacing robust consumption growth of 2.7%. The US remained a net exporter of oil, natural gas and coal last year.

Obviously, there was a lot more going on in the world of energy than I’ve been able to discuss here. And as always, the Review’s data only gets us through last year—so the many exciting developments that have taken place this year will have to wait. But stepping back from the news headlines to look at the objective data can help us make sense of today’s headlines…and tomorrow’s. Have a look at the Review for yourself…and be sure to follow the Baker Institute’s Center for Energy Studies for rigorous, objective analysis to frame your energy thinking…for today and tomorrow.

[i] Note that the Review does not contain data on global energy production; it has data on the production of every individual form of energy, but does not aggregate them (as it does for total energy consumption). I explained the Review’s rationale for this decision in previous years’ commentary, as well as a simplifying assumption allows me to build my own total energy production table for this commentary.

[ii] European imports of Russian refined products were little-changed as the embargo didn’t take effect until earlier this year.

Mark Finley is the Fellow in Energy and Global Oil at the Baker Institute. Before joining the Baker Institute, Finley was the senior U.S. economist at BP. For 12 years, he led the production of the BP Statistical Review of World Energy, the world’s longest-running compilation of objective global energy data.

Read the full article here