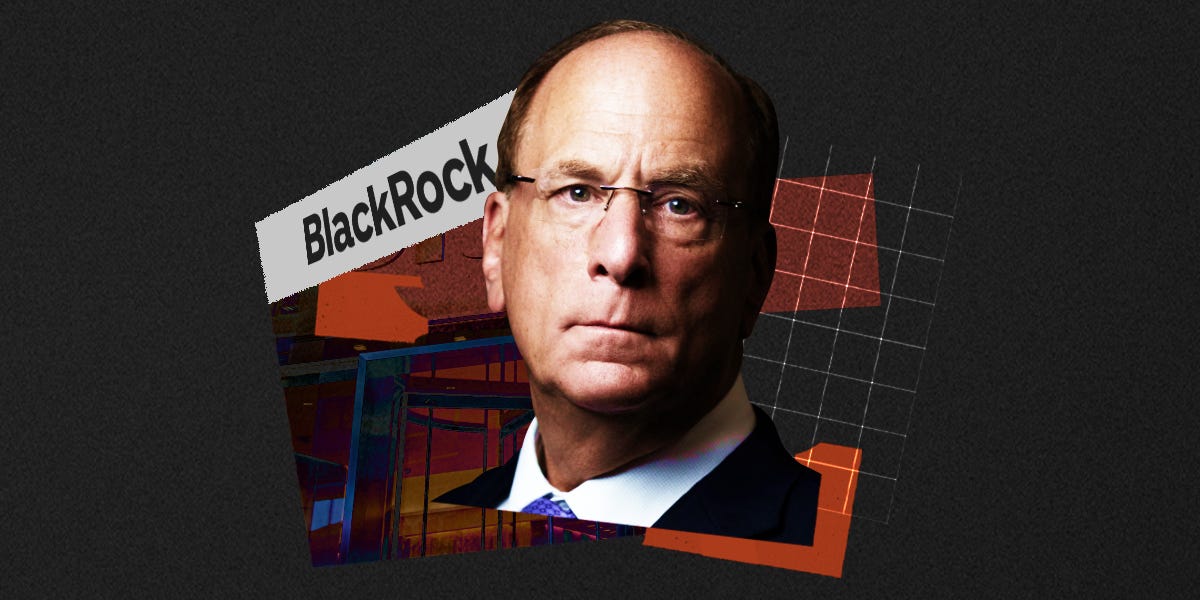

Larry Fink is entering the twilight of a long, successful career after spending half of his life running BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager he cofounded in 1988. It’s been a strange time for the company and Fink personally.

Fink turns 71 this year, and BlackRock’s board has been busy sizing up possible replacements for him. Casting a shadow over his legacy and eventual departure — for which he hasn’t publicly set a timeline — is the anti-environmental, social, and governance investing backlash that has made Fink and BlackRock a favorite political target for Republicans.

The party has now fostered anti-BlackRock and anti-sustainable investing, or “woke,” sentiment so mainstream that at least two US presidential candidates have made it part of their platforms.

Employees and the board alike have taken notice of the growing scrutiny on BlackRock. Some employees have raised concerns internally about how Fink’s open letters and ESG strategy are impacting the firm’s reputation with investors, people familiar with the matter said. Longtime executives have transitioned to roles dedicated to handling client outreach, aiming to curb the criticism from investors like Texas state officials.

“The problem, rightly or wrongly, is with Larry,” a former senior executive who worked with Fink said.

Those concerns persist even though the firm under Fink is performing well. BlackRock drew $190 billion in flows in the first half of this year, its key Aladdin business had a record year in 2022, and divestments by GOP-led states have been limited.

“BlackRock has posted industry-leading organic growth over the last year while most of our competitors are experiencing persistent outflows,” a company spokesperson told Insider. BlackRock did not make Fink available for an interview.

The criticism over BlackRock’s ESG embrace, personified by Fink, has introduced a sticky layer of complexity to what a new generation of top BlackRock leadership will contend with. The question is how Fink’s eventual replacement will handle the backlash that’s centered on BlackRock.

“Serving multiple masters is impossible. There is no way Larry could promote stakeholder capitalism without alienating many current and prospective clients who reject its premise,” said Terrence Keeley, a former longtime BlackRock executive who remains friends with Fink. “And Larry’s successor won’t be able to get this genie back in the bottle. Ultimately, BlackRock needs to prioritize the interests of its shareholders, not some utopian view of the future that many don’t share.”

Fink said during the firm’s investor day last month that he’s “not planning to leave BlackRock anytime soon.” And he has at least one major agenda item he may want to see through that could add another footnote to his legacy: executing a “transformational deal,” as he and executives told analysts and investors they were open to this spring.

Fink has acknowledged his firm is increasingly in the public eye. He said in an interview with Bloomberg in January — a month after an activist investor went after BlackRock and Fink over ESG policy concerns — that attacks on himself and the firm had gotten ugly. “For the first time in my professional career, attacks are now personal,” Fink said.

In turn, $9.4 trillion BlackRock has turned down the dial on talk of ESG.

That’s meant changing the language of how BlackRock talks about sustainability. Fink said last month that he had stopped using the term because it’s become weaponized; his annual widely read letter to investors in March also did not mention “ESG.” And in a departure from recent years, he didn’t appear on CNBC the morning the letter was published to help publicize it.

Last fall, UBS research analysts cited controversy stemming from ESG polarization as a risk for BlackRock and downgraded the stock to “neutral” from a “buy” rating. It was a notable move; sell-side analysts are overwhelmingly optimistic on BlackRock. Since then, UBS has increased its price target as the stock has risen.

Internally, executives have debated ESG policies at length, people familiar with the matter said. Some have left and criticized the concept publicly. Keeley published a book last fall about where ESG investing has gone wrong. Fink, who worked with Keeley for years, wrote in the foreword: “I don’t agree with all of the opinions or conclusions in Terry’s book, but I welcome his contribution, and that of many others, to this critical dialogue.”

Former employees said a peak moment of tension inside the firm last year over the ESG backlash came in the summertime. The comptroller of Texas had issued a list of financial firms he said “boycott” the energy industry and called out BlackRock. Another high-profile move that stoked debate within the firm was BlackRock’s announcement in 2020 that its actively managed portfolios would start removing stakes in companies that generate more than a quarter of their revenues from thermal-coal production. Environmental advocates praised the decision as a positive step in addressing the climate crisis.

Still, people familiar with the firm said they don’t see sustainable investing strategies going away. It’s intertwined across the firm’s divisions; BlackRock incorporates material ESG factors into investment decision-making regardless of whether a fund has a sustainable label. “They’re not going to give up on ESG,” another former employee said. BlackRock sells some 400 sustainable funds and managed $586 billion across its sustainable investing platform as of December, including funds and separate accounts, the firm said in a disclosure on Friday.

Cathy Seifert, an analyst at CFRA Research who tracks asset managers and other financial firms, said the firm could have communicated and explained its ESG practices more effectively before the backlash snowballed.

“I applaud their ESG stance. I criticize the way they defended it,” Seifert told Insider.

That presents a challenge for whoever takes over from Fink. The firm has long planned for who replaces Fink as CEO and Rob Kapito, 66, as president.

Company insiders and people familiar with the firm view a group of longtime top executives, including Mark Wiedman, Martin Small, and Rachel Lord, as possible replacements, Insider has reported. Meanwhile, BlackRock cofounder and board member Susan Wagner is also viewed by some in leadership as someone who could be called on to replace Fink if the board does not have a clear candidate to replace him, Insider reported in May.

“None of these people are household names,” Seifert said of executives who Insider and other outlets have reported as possible contenders to replace Fink. “You saw what some of the large banks did in terms of elevating the profile of likely successors” at firms like JPMorgan and Citi, she said. At BlackRock, Seifert said, “we haven’t seen that yet.”

Keeley, who had overseen relationships with central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and other large clients as head of BlackRock’s official institutions group and left the company last year, said he worries that the firm finds itself in a “Jack Welch-GE quandary.”

“Given no mortal can fill Larry’s shoes, there is a high risk they pick some Jeff Immelt equivalent,” Keeley told Insider. Welch was General Electric’s celebrated, longtime CEO before he handed the reins to Immelt, who oversaw a tumultuous period for the company.

BlackRock has received outsized criticism relative to its rivals. Fink has a far higher profile than Tim Buckley at Vanguard, Abby Johnson at Fidelity, or Ron O’Hanley at State Street.

Fink is more like Jamie Dimon, who also releases long open letters to the investment community and often appears in the media to discuss JPMorgan and views on the economy. Each has been rumored to have been on short lists for public office in the past. But nobody has embraced ESG as a strategy like Fink.

Part of warding off criticisms that it exerts too much influence on other companies through its funds’ stakes has meant opening up more options for investors to decide how they’d like to vote their shares. On Monday, BlackRock announced that it planned to expand such a program to shareholders of its largest ETF, the $342 billion iShares Core S&P 500 ETF.

Fink chose to make his letters public, which leads to concerns that Fink wrote them as a PR exercise.

Alex Edmans, a finance professor at London Business School who wrote in a widely read paper on ESG’s branding problem, said Fink has become synonymous with arguments both for and against ESG because of his public positions on the concept.

“Investors engaging with companies to hold them accountable for creating long-term value is often desirable. However, the most effective engagement is typically private,” Edmans told Insider. “Fink chose to make his letters public, which leads to concerns that Fink wrote them as a PR exercise, to position BlackRock as a leader in sustainability and attract clients, rather than a genuine desire to make companies better.”

As scrutiny of the firm has mounted, teams aimed at managing the firm’s reputation have changed and grown to reflect that.

BlackRock’s public profile has risen in recent years, “and with it the need for us to engage with more people in more places to understand their perspectives and tell the BlackRock story,” Fink wrote last month in a memo to employees that Insider viewed. Fink announced in the memo that the firm had hired a global head of corporate affairs, a newly created role overseeing the brand, global communications, and other functions.

At the firm’s investor day last month, Fink said he’s “not planning to leave BlackRock anytime soon, but BlackRock’s board and I have no higher priority than developing the next-generational leaders for BlackRock, and hopefully, you’re seeing that.”

“I’ve always said that my goal is to ensure that when Rob and I have moved on that the firm is better off than it is today,” he said. “And I’m very confident we’re going to achieve that goal.”

Read the full article here