The average speed of cars in London during a typical weekday averages 8 miles per hour in central London, 12 in inner London and 20 in outer London. According to AI ChatGPT, “based on historical accounts and estimations”, the speed of a Roman chariot was likely around 20 to 25 miles per hour on well-maintained roads in ancient Londinium. It would be obviously unfair to lay this lack of progress in the speed of urban transport in London over the intervening 2,000 years solely at the door of the city’s mayor Sadiq Khan.

But fair or not, the two-term mayor who is up for re-election next year, will have to face up to the wrath of a section of London voters who depend on their older ‘non-compliant’ cars for their daily transport needs. Mayor Khan seems to have provoked an incipient rebellion by ordinary motorists with his plans to expand the city’s ultra-low emission zone (“Ulez”) to the outer suburbs of Greater London, an area three times larger than the current Ulez zone.

Enough Is Enough

A month ago, I reflected in these pages on “the theory of effective pain.” The theory states that when governments impose financial penalties on their voting public for alleged “long term climate benefits”, there comes a point of inflection when the latter’s limits of tolerance are breached with consequences at the ballot-box.

Well, I told you so…

In by-elections held on Thursday, contrary to the polls which predicted an easy Labour victory for the Uxbridge and South Ruislip seat vacated by former prime minister Boris Johnson, the seat remained in Tory hands albeit with a narrow majority. The party suffered heavy electoral defeats in two other seats (as expected). Leading government ministers, backbenchers and advisors warned Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to ease up on net zero regulations which will cause further pain on ordinary citizens already struggling with the cost-of-living crisis.

In an interview with the Telegraph, Michael Gove became the first cabinet member to comment on inflexibly applied regulations in an environmental “religious crusade” — in particular, the bans on diesel and petrol cars from 2030 and on gas boilers for home heating from 2025 — which would lead to a “backlash” from voters. Former Tory leader Sir Iain Duncan Smith became the latest MP to call his party members to “rethink” net zero in light of the by-election results. He writes that the Conservatives “must stand against net zero” and that Ulez has become “a lightning rod, a moment when politicians had to face up to the fury of people having yet another tax imposed on them.”

It is no surprise that a news report published on Friday pointed to a sharp increase in vandalism on the 1,750 numberplate-reading cameras that Transport for London (TfL) is installing in preparation for the Ulez expansion due to be implemented in August. Popular social media commentator Katie Hopkins made a parody of how people are using cheap filling foam to vandalise Ulez cameras.

Social Justice and Health Benefits Of Congestion Charges

Mayor Sadiq Khan introduced Ulez in April 2019 which charges a daily fee of £12.50 on older more polluting petrol and diesel cars which enter Central London. In October 2021, the zone was extended to cover the area within the North Circular and South Circular roads. Will the zone be extended to cover all of Greater London next month as planned by the mayor in his signature green policy for the city? He has come under pressure to reconsider the Ulez expansion after Labour failed to win the Uxbridge by-election. But, according to The Guardian, the mayor has refused to back down on its implementation as scheduled but “is open to new ideas for mitigating the impact of the anti-pollution levy.”

The introduction of Ulez did not cause much controversy, as people were open to the idea of a less congested, more pleasant city centre. A dense bus and subway transport network helped alleviate the restrictions on older vehicles in Central London. The outer suburbs however cannot support high-frequency public transport schedules. Pensioners, tradesmen and owners of small businesses depend on their older cars and vans to get around or support their work chores. Unsurprisingly, the suggestion by Labour MP David Lammy that plumbers or electricians take the Tube for their jobs was widely met with derision.

It is not just London and its Ulez expansion plans. Across towns and cities in England such as Birmingham, Bristol, Cambridge, Canterbury, Glasgow and Oxford, the imposition of low traffic neighbourhoods, raising the cost of parking, the narrowing of roads for bicycle lanes, the putting up of bollards and planters to restrict car traffic altogether and experimenting with zoning restrictions for “15-minute cities” have become common. London itself is now the most congested city on earth, ironically caused by its war on working class motorists.

This war on private cars is in keeping with the World Economic Forum’s ambitions for governments to reduce the number of automobiles in the world by 75% by 2050 to reduce carbon emissions from the transport sector. In the WEF’s green agenda, there is little if any recognition of what the loss of affordable private transport entails for ordinary people. Tradesmen like plumbers and electricians who depend on their vans for work, mothers who drive their children to and from school or go shopping, disabled or older people who need to visit their loved ones or go to hospital matter little in the elite’s war on cars.

Mayor Khan has claimed overwhelming support for his Ulez expansion scheme although there were complaints about the integrity of the consultation process based on documents obtained through freedom of information requests. A YouGov poll commissioned by the mayor found that only 27% of the respondents were against the Ulez expansion as a means to “to tackle air pollution” while 51% were in favour. A competing poll, undertaken by the Tories, asked respondents whether they were for or against the expansion with the preface that it was undertaken for revenue raising purposes. This reversed the results, with 51% opposed to the expansion, and 34% supporting. Biased surveys are nothing new, and poll results depend on the framing of the question.

Given the long run nature of climate change and “saving the planet” from an allegedly impending climate catastrophe, the public relations approach of the mayor’s office in pushing for the Ulez expansion has focused on the health effects of polluted air. Ostensibly at least, Ulez is about air quality and the health of Londoners. For mayor Khan, air pollution is a social justice issue: “For me the issue is very simple: it’s one of social justice… It’s the poorest people, least likely to own a car, least likely to cause the toxic air problems, who are most likely to suffer the consequences.”

But like the questionable survey results for Ulez expansion cited by the mayor’s office, the data on air pollution in London is contrary to its assertions. Khan’s office claims that since 2019, there has been a fall of 46% in nitrogen oxides and a 41% reduction in PM 2.5 (particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometres in diameter). Yet this comparison is based on questionable counterfactual modelling of what “would have occurred” if there were no Ulez in operation. Ross Clark of The Spectator “smells a rat” here and refers to a study by Imperial College which examined air pollution data for 12 weeks before and 12 weeks after the original Ulez was implemented in 2019. It found that there was no significant reduction in PM 2.5 pollution and nitrogen oxides fell by a mere 3%.

A report by the Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants claimed that air at Hampstead station, the deepest Tube station in London, had a particulate matter concentration 30 times worse that standing by a busy road in the capital. A 2019 estimate of the social costs of air pollution from cars in the UK found that it amounted to £25 a year or less. In other words, just two entry fees for the Central London Ulez would cover the social cost of this pollution for a whole year.

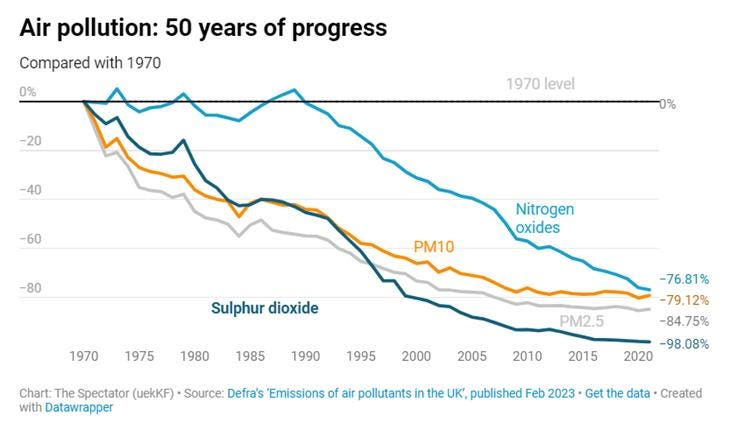

London’s air pollution levels have dramatically declined over the past 50 years along with that of other major cities such as Tokyo and New York which were known for their smog-filled skies in the 1970s. The reduction of coal burning in households and old power plants, more efficient vehicles using better quality diesel and petrol, and the use of natural gas for power generation, home heating and cooking are among some of the factors that have led to far cleaner air in most cities in the developed OECD countries.

Is the Tide Turning?

In March, Dutch voters went to polls and put the populist Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB) into the lead, ahead of the governing party, in the Senate, redefining the country’s political landscape. It is opposed to the government’s plans to decimate the Dutch farming industry, the world’s 2nd largest agricultural exporter, in yet another environmental scare: nitrogen fertilizers which emit nitrous oxide (N2O), a greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere.

In June, a YouGov poll found that 20% of German voters would vote for the AfD, making it the second-strongest party behind the centre-right CDU (28%) and ahead of Scholz’s SPD (19%). The resurgence of AfD, invariably dubbed a “far right” party by the mainstream media, has been at the expense of the Green party which has been pushing burdensome climate change policies. The proposed ban on oil and gas heating systems from 2024 may well be the proverbial feather that breaks the back of green agenda pursued by the Scholz coalition government.

Political opposition to virtue-signalling green schemes has been growing across Europe and London’s motorists are leading the country’s first real anti-green citizen’s revolt. Mayor Khan may have badly miscalculated his Ulez expansion plans, as argued by Matthew Lynn of The Telegraph. Susan Hall, the Conservative candidate for next year’s London mayoral elections, has vowed to scrap the Ulez expansion and the TfL’s funding of low traffic neighbourhoods if voted in.

Will the motorists of London unite to make this happen?

Read the full article here