Cities across America are undergoing big changes. The shift to remote work early in the pandemic allowed wealthy residents to ditch big cities in droves and set up shop in smaller cities and towns nearby. This mass reshuffling caused huge spikes and dips in populations, and nearly every locale across the country has felt the impact at some point. For instance, the Hudson Valley — the constellation of small cities and towns north of New York City — saw a massive influx in 2021 of over 30,000 residents who ditched their Manhattan apartments for farmhouses. Midsize cities across the US like Austin, Texas and Charlotte, North Carolina have seen a similar boom in newcomers. Now that the dust is settling, increased rents and the stickiness of working from home have pushed small and midsize cities to adjust to a new normal.

While the surging costs of housing and the new freedom of remote work helped trigger this mass migration, small cities have been laying the groundwork over the last decade to entice these big-city refugees. The new playbook for up-and-coming metros, which I detailed in my book, “The City Authentic: How the Attention Economic Builds Urban America,” is to engineer the entire city to produce the kind of amenities that middle- and high-income workers have come to expect from an urban neighborhood — walkable downtowns, diverse restaurants, craft-brew pubs — at a fraction of the price. These cities want to convince potential transplants that they can have it all. “To a growing degree,” the New York Times recently reported about those leaving large metros, “what they left behind they can find in Charlotte, Denver, Minneapolis, Salt Lake City, Dallas or Louisville.”

But these urban-renewal projects come with a dark side. Sure, they have been successful in attracting young professionals to what were once considered second- or third-tier cities, but they have also turned cities across the US into replicas of each other. In their attempts to stand out, many places have started to look exactly the same.

A fight over the creative class

Most people don’t think of the 1988 Tim Burton film “Beetlejuice” as a tale about urban development. But the Deetzes, a family who moves into a newly-haunted house, are a classic 1980s striver couple — a real-estate agent and a self-described artist — who can’t help but transform everything in their sleepy Connecticut town into some sort of consumable experience for city folk just like them. While perhaps a bit overdone, the Deetzes are the perfect pop-culture example of the type of people cities have been trying to attract for the past 40 years.

As America’s manufacturing jobs shifted abroad and city governments cut back on investment in the 1980s and 1990s, the finance, insurance, and real-estate industries emerged as the biggest business concerns in urban America. Unlike factory work, these businesses employed fewer, better-paid, white-collar office workers who had much more flexibility in where and when they worked. This burgeoning “creative class,” as the urban-studies theorist and professor Richard Florida called them in his 2002 book, “The Rise of the Creative Class,” was composed of graphic designers, web developers, and marketing professionals. The most creative and economically successful cities, Florida argued, were ones that catered to the lifestyles of these highly mobile professionals. In response, cities across the globe sought to establish cosmopolitan downtowns that would be welcoming to upper-class creatives.

Smaller cities, meanwhile, struggled to attract good employers and develop successful entrepreneurs. In 2017, Florida wrote “The New Urban Crisis,” which admitted that the approach he spearheaded had significantly contributed to a “winner-take-all urbanism”: Big cities grew, but small and medium cities withered.

Then came the pandemic, and remote work suddenly made small cities a viable home for wealthy professionals. The New York Times reported in May that the middle class was being priced out of big cities, which, collectively, lost over 200,000 people in 2021. After a 40-year march to a few major urban centers, the eyes of the “creative class” began to wander across the map. Many workers relocated to cities of less than a quarter of a million people, a class of city that hasn’t seen a net increase in population in over a decade. But the cities that were able to capitalize on this shift were the ones that executed on what I call the “city authentic” playbook.

The rise of influencer cities

Beyond jobs, cities also have the ability to attract residents by being, well, attractive. At the turn of the 20th century, the “city beautiful” movement launched: Governments and businesses built massive, ornate buildings in an effort to attract further investment. For example, the Washington, DC we know today — from the grand National Mall to the iconic neoclassical buildings — wasn’t formally laid out until 1902 as part of this movement.

The second such movement was the “city efficient” model, which leveraged Space Age technologies to modernize cities with precise engineering and strict use-based zoning laws. The national-highway system is perhaps the most transformative example, but this movement also gave us the modern steel-and-glass skyscraper.

For the past two decades, cities have turned to an economic development strategy I’ve deemed “the city authentic.” The new movement is largely predicated on nostalgia and the fetishization of “the local.” The pitch that cities using the “city authentic” playbook make, regardless of their particular amenities, is fairly similar: Their city is the “thrift-store find,” compared to the mainstream brand of major metropolises. They have old architecture that has been transformed into new, trendy offerings — all for a cheaper price.

The aging buildings’ authenticity reassures millennials that they are not living in their parents’ cookie-cutter suburbs. They are experiencing something real. Their brunch means something.

An ad from the Fulton County Industrial Development Agency, or IDA, in upstate New York highlights its “historic, grand buildings that feature distinctive architecture, 100-year-old brick, and hardwood floors, surrounded by plentiful and free parking.” In a Southern Living write up from last year, Athens, Georgia — a town of 120,000 — boasts that “an old tire company is now a favorite brewery and farmers’ market. A kudzu-covered former cotton warehouse returns as an arts district,” while the Athens Quality of Life Guide emphasizes that median rents are “$200 less than the national average.” Tulsa, Oklahoma even offered $10,000 to anyone who would move there for remote work — touting the city’s “revitalized Arts District that boasts hip coffee shops, vegan taco joints, steakhouse speakeasies, whiskey bars, art galleries, coworking spaces, and a software-development school.” In other words, these cities offer relative affordability without sacrificing the hip feel of an urban neighborhood.

In a post-industrial economy such as ours, whether a city can attract new residents and investments can mean life or death for its local economy. But the challenge for cities following this playbook is balancing uniqueness and approachability. There is immense pressure to, paradoxically, fit in and stand out. Most square this circle with predictably unique cultural offerings: Craft breweries that offer the same litany of IPAs and lagers, but with each one named after something local; food halls with the same overpriced plates and decadent bloody marys, but everything is made locally; and, as Fulton county’s IDA would like us to remember, it is all contained within beautiful brownstones and Victorians that were spared urban renewal’s bulldozers. Years of neglect are turned into an asset because the aging buildings’ authenticity reassures millennials that they are not living in their parents’ cookie-cutter suburbs. They are experiencing something real. Their brunch means something.

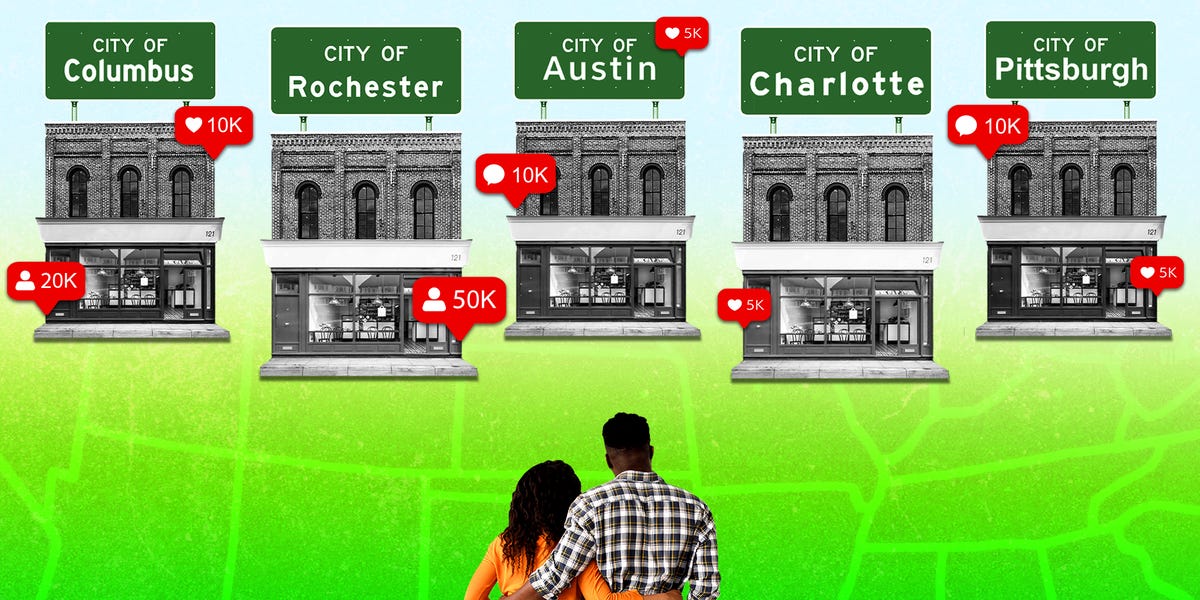

And, because so much of how we persuade and influence each other happens online, cities are increasingly making that case on social media with the help of influencers. Whether a dive bar or an entire neighborhood is perceived as unique and on-trend has a lot to do with how it circulates online. Social media and its attendant influencer industry have significantly changed how cities promote themselves. Ignoring the conflicting struggles that characterize the history of America’s downtowns, the city authentic weathers that history down to a safe, entertaining story told through predictably unique experiences, menu items, and interior designs. All of which are meant to both stand out just enough to recognizably fit into the categories, genres, and vibes organized by social media’s algorithms.

Real-estate agents now feel the pressure to up their Instagram game to promote not just their properties, but an entire market. It’s considered a dereliction of duty if your downtown Business Improvement District doesn’t have a social-media plan and someone to execute it. And, whether they’re home-grown or hired from an agency, being featured on an influencer’s account is a common tactic to raise a city’s profile among young professionals. When the influencer chef Alison Roman needed to escape both COVID and a high-profile spat with Chrissy Teigen, she decamped for upstate New York, and subsequent interviews touted her investments in out-of-the-way Bloomsville, New York. Some influencers have even gone so far as to make their own apartment sponsored content.

Tired replicas

While there is economic relief for those leaving the big cities for chic and affordable spots, it’s not all rosé brunches and glamping. There are real challenges and even a few dangers to using the “city authentic” playbook. As big-city high-earners move into town, landlords and restaurateurs immediately move to cater to them, raising prices and accommodating new tastes, which pushes out locals. As I demonstrate in my book, in upstate New York, Rensselaer county’s population only went up 1% between 2010 and 2019, but median gross rent went up 25% over the same time span. It spiked even more during the pandemic when change of addresses from New York City jumped a whopping 787%.

I used to rent a one bedroom for $600 a month when I first moved to Troy, in Rensselaer County, in 2010. Since then, the availability of housing in that price range has gone down by 36%. And this trend is happening all across the US, threatening to make it impossible for essential workers like nurses, cooks, and teachers to live anywhere near where they work. The nine counties immediately north of New York City may have absorbed a lot of high-earning city folk, but even more people left the region due to rising prices, resulting in a small net loss of population between 2019 and 2020.

And as the local haunts are replaced by Instagramable cafés and art galleries, the city feels less like home and more like someone else’s lifestyle brand. The pressures to be predictably unique can suffocate the distinctive identity that begat a region’s success in the first place — turning cities into tired replicas of each other.

And none of this guarantees financial success, either. City governments, eager to win the all-against-all fight for capital investment, are happy to offer tax-break enticements to developers. So while construction cranes may signal economic success and there may be an influx of cash from building permitting and new residents’ spending, cities will eventually find that there’s no money to repair the roads and pipes that lead to all this new development. All the emergency calls and trash these new apartment buildings generate need to be dealt with too, and that costs money.

It is worth saying that there is nothing wrong with enjoying your weekend farmers-market jaunt (I know I do). Making a city that’s exciting, fun, and inviting is an unalloyed good thing. But the default way cities do it now is creating unaffordable and uninspired cityscapes.

To avoid these challenges, some cutting-edge cities have gotten creative. Newark, New Jersey set up a revolving loan fund to convert privately held small businesses into Employee Stock Ownership Plans, which have been recognized as a great way to keep money in a community after a business owner retires. Other cities could reverse a trend that began in the 60s where satelite communities and suburbs formed their own (usually whiter and wealthier) municipal governments, splitting city resources. Reconsolidating cities would reduce overhead costs of running them and increase the quality of the essentials: water, public safety, and waste disposal.

Housing is also a crucial piece of the puzzle. While some cities definitely need to increase supply, research suggests that this “will never supply adequate housing for low- and moderate-income households.” Rent control and public housing are important tools here, but another option that may be less politically contentious is the formation of a neighborhood trust. Unlike renting, neighborhood trusts like the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative in Boston allows residents to manage permanently affordable housing on their own terms while also building up a bit of equity.

Regardless of their approach, cities that have borne the brunt of the large-city exodus will need to manage their sought-after growth sustainably. If they don’t, the hype of America’s new Generic Towns is certain to fade.

David A. Banks is a lecturer and Director of Globalization Studies at University at Albany SUNY. He is also the author of “The City Authentic: How the Attention Economy Builds Urban America,” and the officer for contingent faculty for his union, UUP.

Read the full article here