Eighteen months into war between Russia and Ukraine, the conflict has become nearly invisible to many Americans. News from the front is frequently reduced to a few sentences, and each new day’s reporting sounds like yesterday’s.

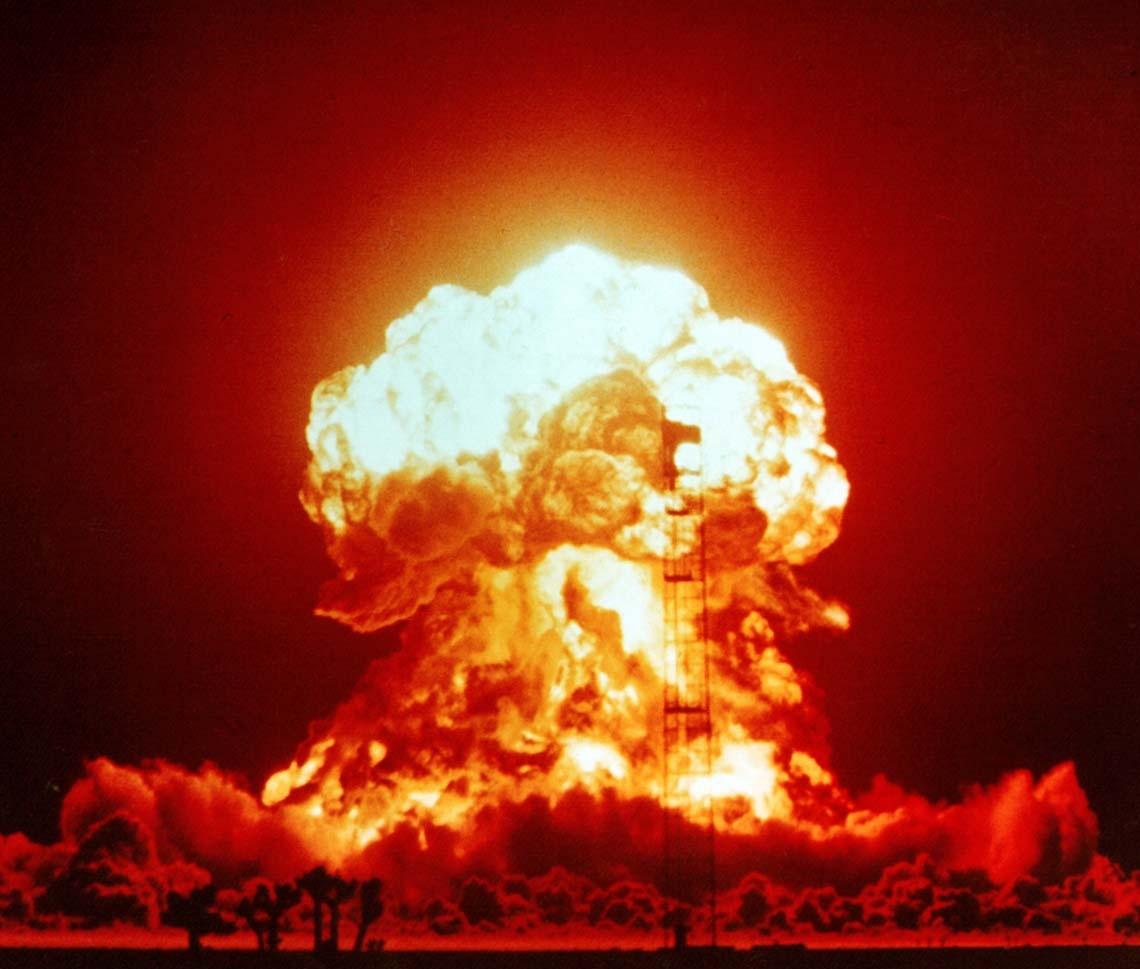

As Western nations have gradually crossed every “red line” laid down by Russian President Vladimir Putin, Moscow’s repeated warnings about the possibility of nuclear weapons being used have ceased to elicit fear.

Thus, when Deputy Chairman of the Russian Security Council Dmitry Medvedev warned on June 30 that success of the current Ukrainian counter-offensive might provoke a “nuclear conflagration,” his comment was barely noticed. Some Western observers seem to have concluded such statements are a bluff, despite the frequency with which they are issued by senior Russian officials.

The Biden administration takes the warnings seriously, and has sought to find a middle ground between doing too little and doing too much in arming Kyiv. Nonetheless, there is inherent danger in supporting war on the doorstep of another nuclear power. Nobody in Washington can claim to understand with any precision what Putin’s inner circle is thinking, or how it might react to a variety of plausible developments.

Against that backdrop, here are five scenarios in which Moscow might decide to “go nuclear.” Since US planning scenarios typically anticipate that the nuclear threshold initially would be breached in a limited and local way, I will confine myself mainly to situations in which Russia employs tactical weapons—of which it has roughly 1,900.

Russian conventional forces falter on the battlefield. The performance of Russian forces in the war has been so poor that further battlefield reverses cannot be discounted. In addition to various disabilities noted to date, Moscow’s military now faces growing shortfalls in the availability of precision munitions, and the loss of Wagner Group mercenaries on the front line.

At some point, the limited use of lower-yield nuclear weapons might come to be viewed as the only available option for staving off defeat. Moscow has a variety of weapons stationed near Ukraine such as the Iskander missile that are capable of delivering both conventional and nuclear warheads, and failing in that it could fall back on its under-utilized air force.

Initial nuclear use would likely be confined to Ukraine, and designed mainly to shock Kyiv into submission. Putin has good reason to believe that any such application of force would result in a complete rethink of Western strategy for the conflict.

Ukraine threatens core Russian interests. Kyiv is gradually stepping up its attacks on targets inside Russia. If these operations were to begin having a significant impact on governmental or economic infrastructure, they could provoke a nuclear response pursuant to longstanding Russian nuclear doctrine.

The West does not have a fine understanding of how Putin & Co. define their nation’s core interests, and whatever views they currently harbor are subject to change as the fortunes of war shift. For instance, an invasion of the Crimean Peninsula might be deemed a threat to Russia’s core interests even though it was only annexed by Moscow nine years ago. The possibility of limited and local nuclear use is increased by the fact that Kyiv has no capacity to respond in kind.

Moscow misreads military signals. The worse the war goes for Moscow, the more Putin’s inner circle will retreat into a siege mentality where fear takes the place of calm deliberation. In such circumstances, it is plausible that ambiguous indications of military action rendered by a mediocre intelligence system could lead to a precipitous response.

It would not be the first time that Moscow misinterpreted intelligence. Anthony Barrett of the RAND Corporation reports that in 1983, a NATO military exercise called Able Archer was misconstrued by Russian leaders as cover for a nuclear attack.

That happened in the absence of an actual conflict. Today, with war raging daily near Russia’s border with Ukraine, the possibility of making mistakes is more elevated. After all, Moscow is within range of tactical aircraft that might operate out of Ukraine.

Central control of nuclear forces breaks down. It is a longstanding assumption of Western military planners that Moscow maintains a tight rein on its nuclear forces. However, the quality of technology and training of personnel in the nuclear command-and-control system may have deteriorated in much the same manner that other facets of the military establishment have.

That is particularly true of the theater or tactical nuclear systems that Russia deploys near Eastern Europe. Many of the systems are road-mobile, and thus must be entrusted to local commanders who might have their own ideas about how to respond in an emergency. If the Russians are sensible, such systems do not carry nuclear warheads unless they are under alert for imminent action; but Ukraine could constitute just such a situation.

Whatever the formal procedures are for releasing control of nuclear weapons to local commanders, the performance of Russia’s military in the war to date has been so uneven that there can be no ironclad guarantee against unauthorized use—or for that matter, accidental use in a military exercise.

Putin deposed by extreme nationalists. The Ukraine war has given voice to extreme nationalists in the Russian political culture who frequently invoke Russia’s nuclear arsenal in proposing paths to victory. President Putin has tried to tap into nationalist sentiment, but as the recent revolt of Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin demonstrates, that is a dicey game.

What if Prigozhin, or players of his ilk, sought to seize some of Russia’s nuclear weapons? What is they conspired with military leaders to depose Putin and bring a more “decisive” style of leadership to Russia? At that point, all bets would be off and Western capitals might view Putin’s tenure in a different light.

Does this sound fanciful? Perhaps it is. But the simple fact is that the inner workings of the Russian political system are largely opaque to the West, and thus planners need to consider a range of perilous possibilities. If Moscow resorts to the use of nuclear weapons in Ukraine, the White House will need a quick answer to the question, “now what?”

Read the full article here