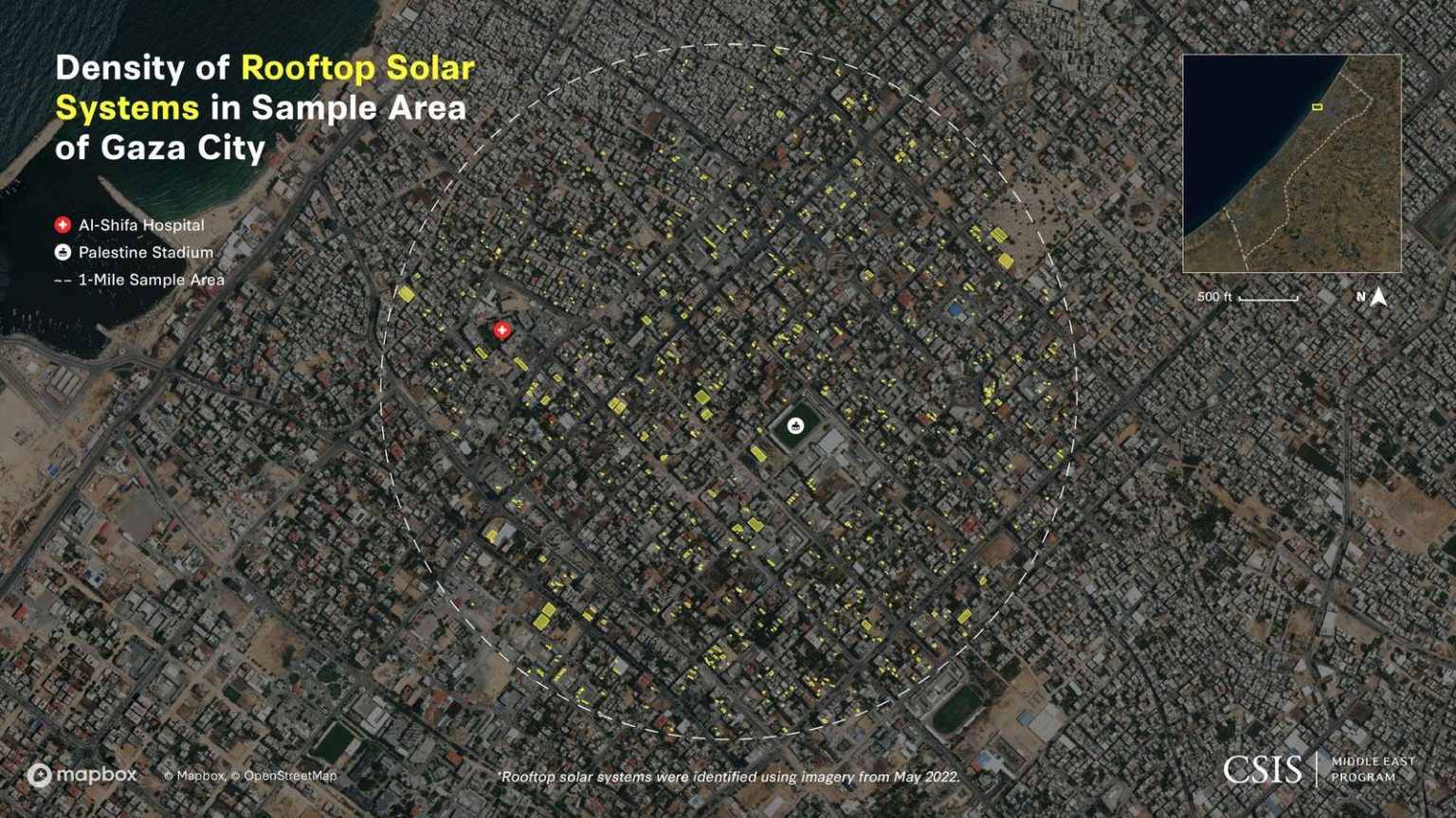

The Gaza Strip has an estimated 12,400 rooftop solar systems, likely representing the highest density in the world. Despite damage they still provide dwindling power.

A new report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) details the role of solar power in Wartime Gaza. Based on extensive and detailed study of commercial satellite imagery, the report underlines both the resilience and vulnerability of small-scale solar power systems in conflict zones.

Co-authored by CSIS’ Middle East program deputy director, Will Todman, and colleagues, Joseph Bermudez Jr. and Jennifer Jun, the report concludes that future combatants will likely seek to reduce adversaries’ access to solar power.

As they do so, vulnerable populations will simultaneously seek increased access to solar power to help them survive conflict. In other words, the war for energy within War will remain much the same as it always has.

“The analysis we did indicates that Gaza probably has the highest density of rooftop solar in the world. That’s not the same as saying it has the highest solar capacity,” Todman explains. Other locations like Honolulu, Hawaii generate much more solar-derived electricity via larger capacity rooftop systems he notes.

But in Gaza as in Lebanon and Yemen, local people have acquired small, easy-to-obtain rooftop solar systems to make up for chronic shortages of electricity from public grids. In prewar Gaza, Gazans reportedly only received power from the grid for six to eight hours per day.

Before the most recent conflict, half of all Gaza’s electrical power came through 10 Israeli power lines according to the CSIS report. A single diesel power plant in Gaza generated an additional quarter to one-third of the power supply with fuel purchased from Israel and financed by Qatar. Informal private solar-power and other systems provided the remaining 25 percent of electricity in the Gaza Strip.

Some 320 days of sun per year over the territory make solar power viable. Though it has periodically restricted their importation, many (probably most) of the rooftop solar systems installed in the Strip were acquired through Israel.

“[Rooftop systems] provided [Gazans] with some resilience, with some autonomy, and ultimately allowed them to get on with their lives when others around them were plunged into darkness,” Todman affirms.

Hamas’ attacks of October 7 and the subsequent war have changed that. The CSIS report points out that rockets fired by Hamas at Israel on October 7 destroyed some of the electrical lines that supply Gaza from Israel. At the same time, Israel cut off the Strip’s external electricity supply and blocked diesel imports resulting in the shut-down of Gaza’s sole central power plant on October 11.

Inevitably, fighting has also destroyed solar systems on critical infrastructure. The satellite imagery that Todman and his colleagues reviewed shows evidence of damage from Israeli strikes to larger scale solar infrastructure, including that powering a German-funded Gaza wastewater plant. However, assertions that Israel has deliberately targeted rooftop solar are “very tricky” Todman cautions.

“I don’t know that Israel has deliberately targeted solar panels linked to Gaza’s infrastructure. They have been hit, possibly when aiming at Hamas fighters in between panels or during airstrikes. It’s hard to be sure but the result is that many of the largest solar systems have been destroyed.”

The very fragility of solar panels and the above-ground nature of solar systems (which makes them relatively cheap, quick to install and connect to the grid) renders them vulnerable to all kinds of debris, shrapnel and detritus common to urban combat. So far, Todman says there is no evidence that non-kinetic means (electronic warfare, directed energy, spraying of obscurants) of disabling small arrays/panels have been used.

Stories about the lack of energy in Gaza and reports from NGOs on the situation there have echoed through the media, amplifying the meaning of the improvised solar power that Gazans have used to cope with the conflict. But the same systems have very probably aided continuance of the fight.

“Ultimately, electricity is always dual-use,” Todman notes. “There is no way to fully ensure that it is used for humanitarian and civilian purposes rather than military purposes. That’s why I suspect Israel will work hard to provide evidence in the weeks ahead that there was some military use of some of these solar rooftop systems.”

That will surely apply to the al-Shifa Hospital and other hospitals in Gaza. An Al Jazeera report from early November asserted that Israeli strikes destroyed rooftop solar panels on al-Shifa but the IDF denied targeting the panels.

The Hospital, like others, has probably relied on its solar system for power during daylight hours as other sources of electricity have disappeared. Todman and his colleagues invested effort in looking at the hospital solar situation at al-Shifa and elsewhere.

“To the best of our knowledge, the [panels] appear to have been physically intact as of November 11. We don’t see clear evidence that [the main two roof installations] were targeted by Israel at that time. Solar panels have been damaged in the vicinity of the Hospital. I’m not 100 percent sure that some of those solar systems could have been powering portions of the Hospital outside of the main complex.”

In order to function, intact solar systems large enough to serve institutions typically require drawing a small amount of electricity from the grid which in Gaza is no longer live. Smaller off-grid systems can provide limited power for charging mobile phones or turning lights on but cannot deliver enough energy to power refrigeration or run accessories.

They remain fragile adjunct sources of electricity in southern Gaza and in spots further north. While they have slowed the depletion of fuel and other supplies for the opening month of the War, their effect is waning CSIS’ report observes.

It is unclear how much power Hamas has derived and continues to derive from rooftop solar or how effectively it has been able to merge solar with other power sources including fuel which it is rumored to have stored and diverted for its own purposes.

Unlike the situation surrounding Hamas’ weapons supply chain, Iran does not appear to have played a role in the proliferation of rooftop solar systems in Gaza Todman says.

“I’ve seen no evidence at all that Iran has been funding any kind of solar infrastructure [in Gaza]. Israel has allowed most of these systems to be imported for typical use.”

The complimentary nature of Gaza (ample sun and flat roofs) and solar power will not be duplicable in many other circumstances. But such systems can offer some conflict-affected centers a level of resilience. While they cannot makeup for the absence of an electrical grid or fossil fuel power, they can underpin a minimum level of functionality for short periods.

“Electricity crises are often deliberate,” Todman observes. “There are people who use electricity access as a carrot to give to allies or prevent energy from reaching adversaries. Ongoing crises often become profitable for elites. The benefits of distributed systems (like solar systems) are that international actors can deploy them sooner in a conflict to provide a minimum of electricity.”

But in war, beneficial systems often dim eventually. How much longer the trickle of electricity from Gaza’s rooftop solar panels can last is difficult to say.

Read the full article here