When the Pentagon asked Ursa Major in 2021 if it would be interested in developing solid-fuel rocket motors for missiles, founder and CEO Joe Laurienti didn’t feel in any rush. The Colorado-based startup believed it had plenty of opportunity producing liquid-fuel engines for civilian purposes like satellite launches, especially as that business was booming with companies like SpaceX.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine and everything changed. As the U.S. and allies fed Ukraine thousands of small portable missile systems to knock out Russian tanks and aircraft, it became clear, to mounting alarm in Washington, that defense contractors weren’t able to quickly replenish stockpiles of those weapons, in part due to industry consolidation that has left the U.S. with just two large makers of solid-fuel rocket motors.

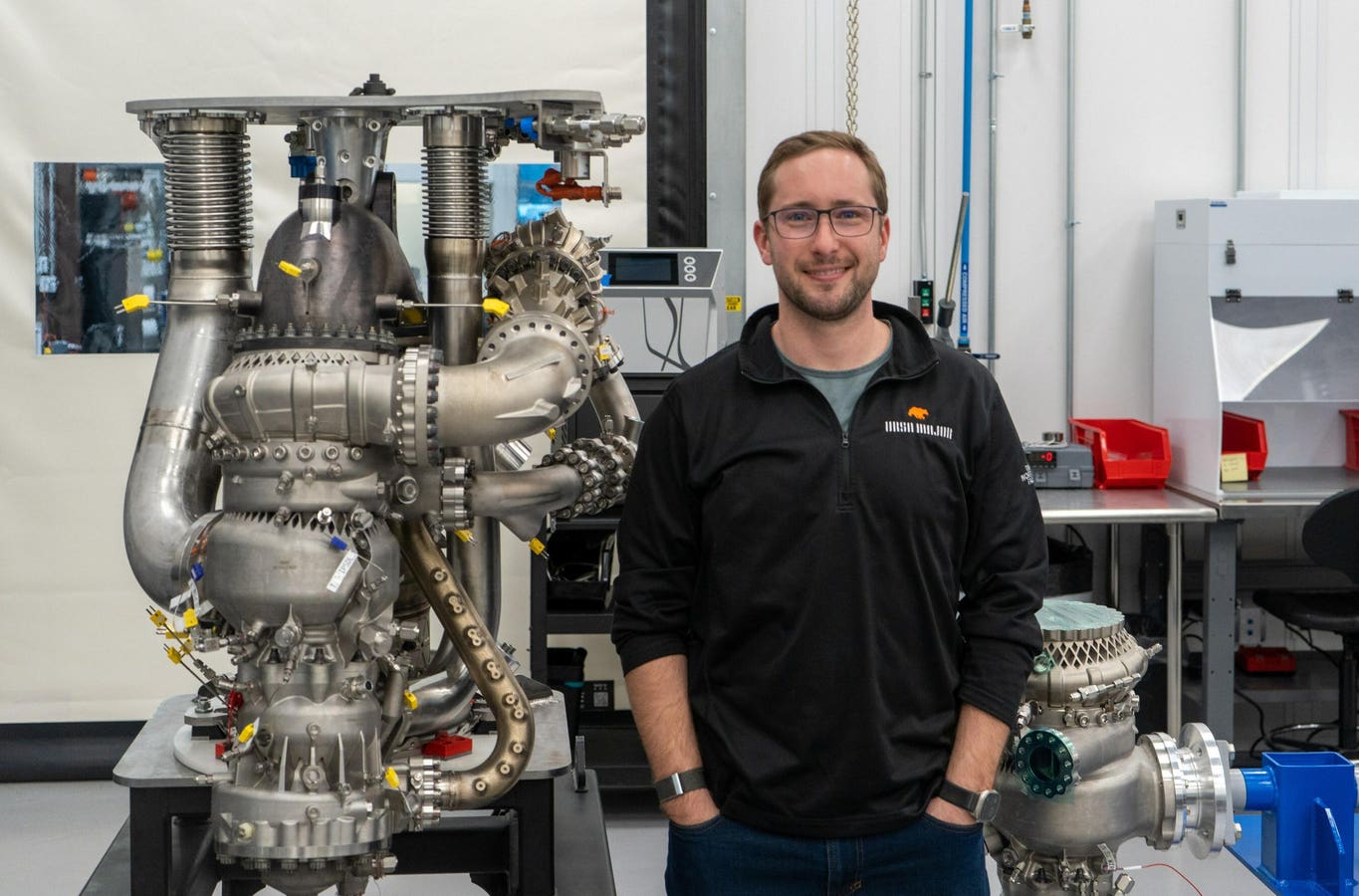

“That was a kick in the rear end to get going,” Laurienti, 33, told Forbes.

Ursa Major began developing a 3-D-printing system that it contends could radically speed up production of solid rocket motors. The startup announced Thursday that it raised $138 million in Series D funding to help the Pentagon reload. The expansion in defense comes after Ursa Major laid off roughly a quarter of its 320 workers in June as its commercial engine business sputtered, with scores of aspiring rocket makers struggling to compete with SpaceX for satellite launch orders.

Among Ursa Major’s new investors is RTX Ventures, the VC arm of the defense giant formerly known as Raytheon. RTX makes the Stinger anti-aircraft missiles Ukrainian gunners have used to deadly effect, as well as Javelin anti-armor missiles, which RTX produces in a joint venture with Lockheed Martin

LMT

Aerojet Rocketdyne and Northrop Grumman’s

NOC

RTX CEO Greg Hayes has complained that Aerojet Rocketdyne isn’t prepared to meet the higher demand. That’s where Ursa Major hopes it comes in. Laurienti said he’s enthused over how RTX could help Ursa Major develop its technology — and become a big customer.

There are plenty of opportunities for the startup. RTX and Lockheed Martin are looking to raise production of Javelin missiles from 2,100 a year to 4,000 by 2026, and Lockheed has said it’s looking for another solid motor supplier for the rockets for its HIMARS launchers, which the U.S. has shipped to Ukraine. The Army wants Lockheed to boost production of the rockets from 6,000 a year to 14,000 by 2026.

It’s not only about Ukraine. “Ukraine has shown that our existing industrial base is just not sized or capable of scaling production to the levels that would be needed if we actually got into a major conflict like a war with China,” Todd Harrison, a defense analyst with the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, told Forbes.

Rival Rocket Makers

Ursa Major is among a handful of startups that are working to fill the production gap in solid rocket motors.

In October, Albuquerque, New Mexico-based startup X-Bow received a $64 million contract from the Pentagon to build solid rocket boosters for hypersonic weapons, which travel at least five times the speed of sound, under development by the Navy and Army. Lockheed is an investor in X-Bow.

In June, Anduril, a Southern California defense tech startup founded by billionaire Palmer Luckey, bought Adranos, which makes solid rocket motors based on a new type of fuel developed at Purdue University. Anduril said it would boost production capacity to thousands of motors a year.

Ursa Major believes the 3-D printing expertise it has built up with liquid-fueled engines will give it an edge. Ursa Major said the production process its developed can make 1,650 solid rocket motor casings a year with a single 3-D printer — almost as much as the current annual production capacity for Javelin. Printed casings have fewer parts and are less expensive than conventionally produced components, and the company said it’s relatively simple to switch to printing different rocket-motor models.

Ursa Major said it has an initial customer for the solid rocket motors. The company declined to disclose its identity.

Founder’s Vision

Laurienti said his vision for Ursa Major has always been to manufacture different types of propulsion.

After graduating from the University of Southern California, Laurienti started out working on rocket engines in 2011 at SpaceX, which was then an outsider looking to shake up a market dominated by government and big defense contractors. After a couple of years, Laurienti jumped ship to Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, where he helped develop the BE-3 engines on its New Shepard rocket, which is now flying tourists to the edge of Earth’s atmosphere.

Engines are the most complicated and expensive part of a rocket, accounting for over half the cost. With the growing commercialization of space, Laurienti thought there was room for an engine specialist that was devoted to developing the best possible technology and could offer lower costs through scale than a vertically integrated company developing its own propulsion.

“Ursa Major kind of came out of wanting to be the Intel

INTC

To get the company going in 2015, he joked, “I sold all my SpaceX stock, and instead of buying a house and starting a family, I bought a 3-D printer, started the company and made my mom cry.”

The first product was a small 5,000-pound thrust engine called Hadley, which was test-fired in 2018. Its development dovetailed with a proliferation of startups developing small rockets to cash in on growing demand to launch small satellites. Constellations of hundreds to thousands of smallsats were being planned by companies like SpaceX, Amazon

AMZN

Proud Builders

But it’s been an uphill battle to sell companies on outsourcing engines to Ursa Major, said Caleb Henry, director of research at Quilty Analytics. “Launch companies are very proud of building engines, so it’s hard to convince them to let go of a central component to creating a rocket.”

Those startups bet wrong that they would be able to offer lower-priced launch services. Their small rockets didn’t cost significantly less to design and manufacture than medium or heavy launch vehicles, Henry said. “You end up in a world where customers that are willing to pay for small launch-vehicle services actually have to pay a premium over the heavy-lift vehicles.”

Satellite-constellation launches have been dominated by medium- and heavy-lift rockets — largely SpaceX’s Falcon 9. In the first half of 2023, SpaceX accounted for about 80% of the cargo put into orbit worldwide, according to the space consultancy BryceTech.

Ursa Major’s Hadley has yet to power a rocket into orbit, and Laurienti acknowledged that its commercial customers are in a tough place, with venture capital funding harder to come by.

“We’ve had to have some really hard conversations with partners in the last couple of years,” Laurienti said.

The result is a company that’s become more focused on weaponry.

One area where Ursa Major’s liquid-fueled engines could succeed is hypersonics. The U.S. is keen to catch up to Russia and China in developing maneuverable high-speed missiles. Stratolaunch, a Seattle-based company founded in 2010 by Paul Allen and now owned by buyout firm Cerberus Capital, is using Ursa Major’s Hadley engine to power a testbed rocket that will be used to subject hypersonic missile components to high-Mach speeds.

In May, the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory awarded Ursa Major a contract that funds development of a 4,000-pound-thrust liquid engine called Draper suitable for use in a target-practice missile that simulates enemy hypersonic weapons.

The contract, which the company has said is “eight figures,” also funds further development of Arroway, a 20,000-pound-thrust, reusable engine intended to be a replacement for Russian-made motors.

With Russia and Ukraine sidelined from exporting rocket engines, Laurienti said he thinks there’s an opening for Ursa Major to support space programs of allies like the EU, Korea, Japan and Australia.

“The proliferation of propulsion is going to continue,” he said. “It’s either going to be U.S. efforts or it’s going to be China’s efforts.”

Read the full article here