On global issues related to energy and the environment, Africa has been much in the news in the past year. Last year, Egypt hosted the UN climate summit (COP27) in November. This was followed by Africa Climate Week in Nairobi, Kenya last month, and now, during 16th to 20th October, Cape Town, South Africa is hosting Africa Energy Week.

It is not possible to generalize across the vast continent, of course. But some facts stand out. Africa is the world’s second largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both aspects. Unlike Asia, Africa remains largely mired in poverty and much of the population has limited access to energy. Poverty and poor access to energy, one suspects, are not just coincidences but reflective of a more general malaise. But what are its governments doing about it? Is there an “African” negotiating position in international forums on energy and climate issues?

Energy Poverty in Africa

Africa’s 54 countries, 3 dependencies, and one disputed territory (Western Sahara) accounted for just over 18% of the world’s population in 2020 but its share of global primary energy consumption amounted to only 3.4% in 2022. In 2019, out of the world total of almost 760 million people without access to electricity, sub-Saharan Africa accounted for almost 590 million or approximately 78%. Africa’s per capita use of electricity in 2022 was 626 kWh, or just 17% of the world average. The continent’s per capita energy consumption in the same year was less than 19% of the world’s average. Reflecting its energy poverty, Africa accounted for less than 4% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions despite its 18% share of global population.

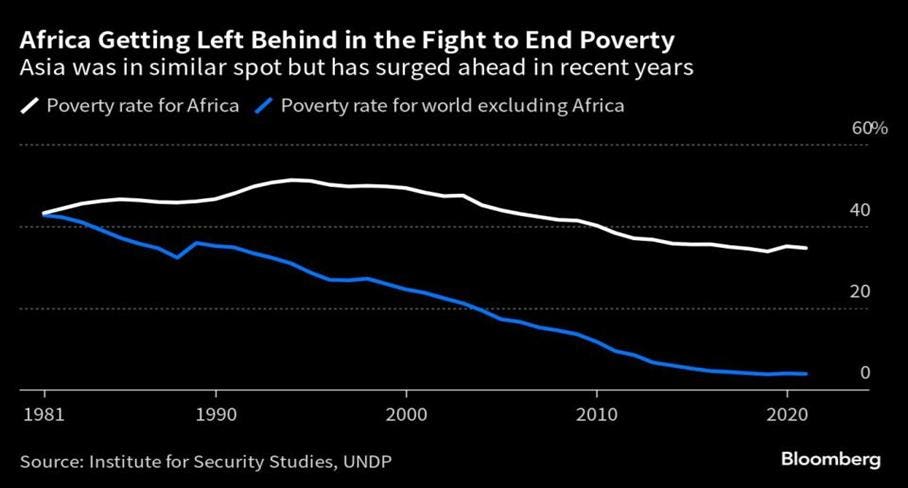

The share of the sub-Sahara African population living in extreme poverty, defined as those living on less than international dollars 2.15 per day adjusted for cost-of-living differences among countries, was 35% in 2021. This compared to the world average of 8.4%. Africa’s performance in reducing absolute poverty has been similarly dismal. While Africa reduced its severe poverty rate by 34% from 1967 to 2021 in real terms (i.e., adjusted for inflation), the world average improved by 78%. China’s rural population was even more impoverished than that of sub-Saharan Africa in 1967. Compared to the 53% of sub-Sahara African population living in extreme poverty in that year, almost 97% of China’s rural population was below that same extreme poverty line. By 2021, however, China had reduced that proportion to less than 1% compared to sub-Saharan Africa’s 35%.

The severe impact of indoor pollution on respiratory health and mortality on Africans has been extensively documented. The death rate in Africa from indoor pollution in 2019 was three times that of the global average. While 69% of the world’s population had access to clean fuels for cooking (such as LPG or electricity), only 19% of Africa’s population did so in 2020. Conversely, the percentage of Africa’s population using dirty solid fuels (such as dung, firewood, or charcoal) for cooking was 77% in 2010; the world average was 41%.

Even more concerning was that while there has been progress in this health metric across the world, Africa’s rate of progress was far slower. Over 1990 – 2019, Africa’s death rate was halved while the average for the world improved by 70%. South Asia’s performance was even better. While it had a worse death rate than Africa in 1990, South Asia’s death rate was reduced by almost 190% compared to Africa’s 50%.

The African negotiating position in global climate talks

The African Group of Negotiators on Climate Change was established at COP1 in Berlin, Germany in 1995 as an alliance of African member states to represent the interests of the region in international climate change negotiations with a common and unified voice. In an interview in June 2022, the Chair of the African Group of Negotiators (AGN) on climate change, Mr. Ephraim Mwepya Shitima of Zambia, was asked about Africa’s priorities and what a successful COP27 (held in November 2022 in Egypt) would look like for the continent.

Mr. Shitima responded, “COP27 should be about advancing implementation of the National Determined Contributions (NDCs), including adaptation and mitigation efforts and delivery of finance to enhance implementation.” Citing the latest IPCC Working group report on “Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability” which estimated the annual cost of climate adaptation in developing countries from $140 billion to $300 billion by 2030, he said that “we are calling for adaptation financing to match these figures…We will also reiterate the importance of delivering the $100 billion a year by 2020 goal that was not met by developed countries.” Mr. Shitima continued, “the African Group will continue calling on developed country parties to meet their obligation and work with other parties to ensure the swift implementation of the climate finance delivery plan.”

What are the responsibilities of the African countries in demanding ‘climate finance’ from the developed countries? According to Mr. Shitima, “Africa cannot continue along the same traditional path which will simply be untenable and costly…in the energy sector, we can no longer continue with the fossil fuels in the long term when the entire world is changing…In terms of our development trajectory, it must be low carbon development and one that will be sustainable.”

At the Africa Climate Summit convened in Nairobi, Kenya in September, African leaders proposed a global carbon tax regime in a joint declaration. The Nairobi Declaration adopted by African leaders at the summit “demanded that major polluters commit more resources to help poorer nations.” It urged world leaders “to rally behind the proposal for a global carbon taxation regime including a carbon tax on fossil fuel trade, maritime transport and aviation, that may also be augmented by a global financial transaction tax”. African heads of state said they will use it as the basis of their negotiating position at November’s COP28 summit.

The bottom line of the African leaders’ negotiating position seems to be as follows:

Africa is poor and responsible for a relatively small share of global carbon dioxide emissions yet suffers from the effects of climate change. Surely the developed countries, who are responsible for most of the historical emissions, need to financially assist Africa in adapting to climate change in any equitable outcome. For its part, Africa will pursue a “low carbon” and “sustainable” development trajectory.

Alas, almost every aspect of this position is false if not self-serving beyond the facts that Africa in general is indeed poor and its carbon emissions are relatively miniscule. To begin with, Africa’s poverty and low rate of greenhouse gas emissions are not unrelated. As Vaclav Smil has conclusively demonstrated, no country in the world has developed without the dense energy available from fossil fuels. Coal, oil and natural gas have powered urbanization, industrialization and agricultural productivity. Going up the conventional energy ladder – from dung and firewood to gasoline, diesel and LPG — has led to improvements in the standards of living for the vast majority of the global population including that of the now-developed countries.

Fossil fuels are the foundational engine of our civilization and an upward spiral in energy consumption is what governmental leaders should strive for. For African leaders to promise a “low carbon” trajectory for economic development – something that has never occurred in human history — in exchange for “climate finance” betrays a naïve belief that the continent can economically develop by “leapfrogging” conventional use of fossil fuels by adopting intermittent solar, wind and battery technologies.

Bootleggers and Baptists in Climate Negotiations

During the prohibition era in the US, Baptists and other evangelical Christians supported laws restricting the sale of alcohol which bootleggers profited from as well. Thus, a coalition of opposing interests, one based on moral virtue of temperance and the other on profits derived from restrictions on legal sales, proved to be a successful combination in enacting legislation on the Sunday closing laws. In this way, strange bedfellows and coalitions of opposing interests such as bootleggers and Baptists that effectively agree on a common rule can be more successful than one-sided groups representing distinct interests.

A similar coalition of opposed interests seems to be driving the position of the African group of climate negotiators. On the one hand, we have environmental NGOs such as the WWF and Greenpeace and their subsidiaries and political supporters in Africa convinced that the “climate crisis” requires a radical curtailment of oil and gas development. On the other are businesses in the renewable energy sector and their political sponsors that benefit from grants and financial aid provided by Western governments, the UN and affiliated organizations in the climate industrial complex.

Not all politically significant voices in Africa agree with the African group of climate negotiators. In the lead up to COP27, Amani Abou-Zeid, the African Union Commissioner for Infrastructure and Energy, said that African countries advocated for “a common energy position that sees fossil fuels as necessary to expanding economies and electricity access.” N. J. Ayuk, Executive Chairman at the African Energy Chamber, is even more forthright: “Africans don’t hate Oil and Gas companies. We love Oil and today we love gas even more because we know gas will give us a chance to industrialize. No country has ever been developed by fancy wind and green hydrogen. Africans see Oil and Gas as a path to success and a solution to their problems. The demonization of oil and gas companies will not work.”

Both Amani Abou-Zeid and N. J. Ayuk are fully aware that asking African governments to leave their fossil fuels resources in the ground in return for “climate finance” from virtue-signaling Western governments and multilateral agencies such as the World Bank to invest on unreliable solar and wind power is not only immoral but infeasible. Africans need all the coal, oil and gas they can get, to achieve rapid economic development for their aspiring populations. Asia is their model, not a hypocritical, deluded West that is now already backpedaling from the “energy transition” that their own citizens are rebelling against as we speak.

Read the full article here