Africa is the second most populated continent, with 1.3 billion people. And climate change is costing it $5 billion to $7 billion yearly — projected to rise to $50 billion by 2030. Nevertheless, the region gets just 3% of the global carbon finance. What now?

That’s according to the African Development Bank, which adds the continent needs $2.7 trillion between 2020 and 2030. That’s a big ask. It may be warranted, but the more prosperous nations promised the less developed ones $100 billion annually in 2009. They are still waiting.

Africa’s first climate summit just concluded, with the most overarching ideas coming from Kenya’s President William Ruto, who is calling for the continent to become a renewable energy hub and for a global carbon tax — to help pay for damages and mitigate potential injury resulting from floods and heat waves. The tax is a hard sell in the United States, especially this close to a presidential election.

“Those who produce the garbage refuse to pay their bills,” said President Ruto, at the summit in Nairobi, Kenya, per the Associated Press. “In Africa, we can be a green industrial hub that helps other regions achieve their net zero strategies by 2050. Unlocking the renewable energy resources that we have in our continent is not only good for Africa, it is good for the rest of the world.”

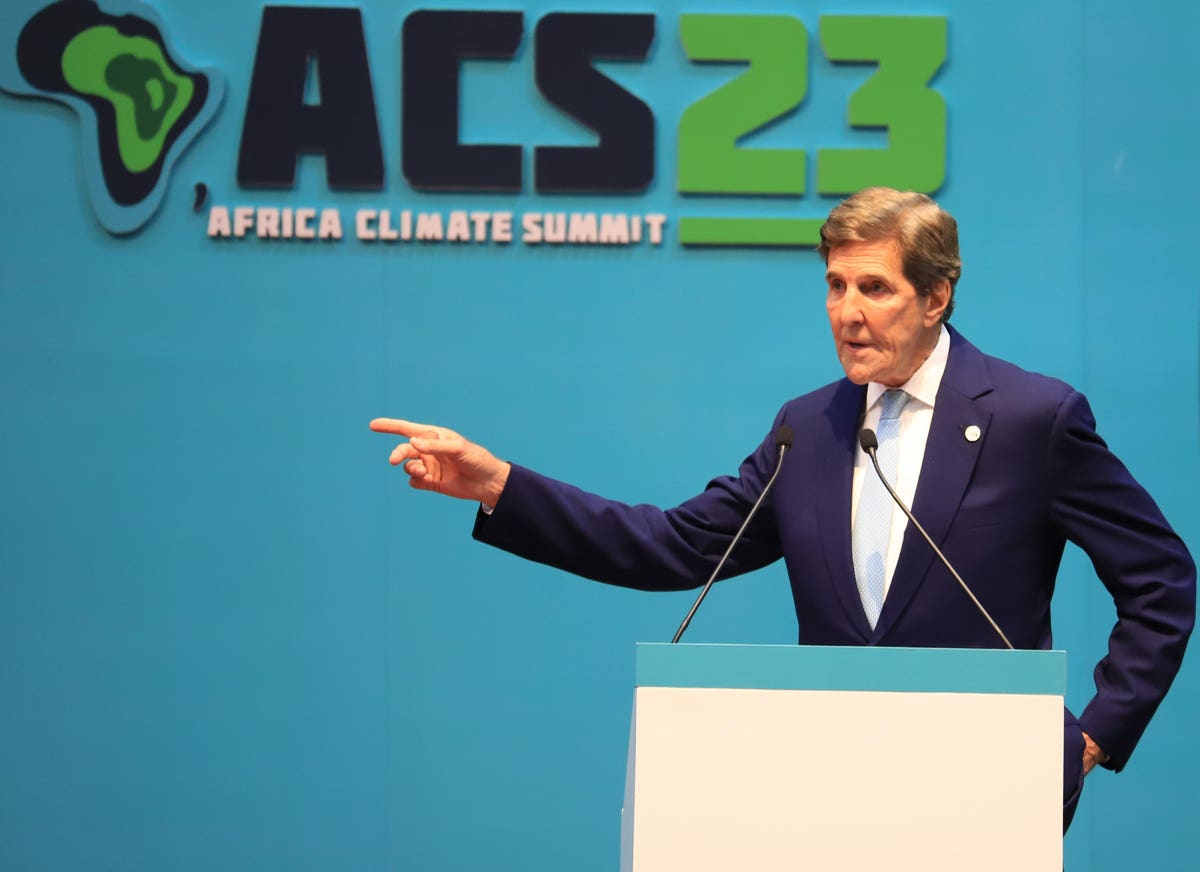

According to the United Nations, Africa contributes about 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions, while the 20 most affluent nations comprise 80%. U.S. Climate Envoy John Kerry added that Africa is home to 17 of the 20 countries hardest hit by climate change. Indeed, cyclones have walloped Mozambique, Malawi, and Zimbabwe while floods have ravaged Nigeria. And the horn of Africa suffers from an enduring drought.

The good news is that the Africa Union — comprised of 55 members — influenced the thinking of the G-20, the world’s most advanced countries. The continent is now part of the newly formed G-21. And sustainability is atop the economic bloc’s agenda.

Low-Hanging fruit is Renewable Energy

Africa is rich in renewable energy resources — not just wind and solar energy but also the raw minerals that go into panels, turbines, and electric vehicle batteries. Look to Mozambique, where renewables power the vast majority of the economy. The caveat: Decarbonization needs more raw materials, requiring developers to extract and process the minerals in African countries and giving foreign investors a greater social license.

“Renewable energy could be the African miracle but we must make it happen. We must all work together for Africa to become a renewable energy superpower,” Secretary-General António Guterres told the African confab.

According to the World Bank, developers have installed more than 700,000 solar systems in Africa. The International Renewable Energy Agency — IRENA — adds that renewable energy, generally, can supply 22% of the African continent’s electricity by 2030. That is up from 5% in 2013. The ultimate goal is to hit 50%. But that requires $70 billion annually: $45 billion for generation and $25 billion for transmission.

IRENA pushes hard for more renewables, saying the climate crisis requires urgency. It reports that 86% — 187 gigawatts — of all newly commissioned renewable energy capacity in 2022 had lower costs than fossil-fueled electricity. That’s saving money: Green energy has cut electricity bills by $520 billion since 2000.

According to IRENA, rooftop solar costs have fallen 89% since 2010, while utility-scale concentrated solar power has dropped by 69%. It added that onshore wind has declined by 69%, and offshore wind power has sunk by 59% since 2010.

“This transition is going to happen, in my judgment because the private sector gets involved in a much greater degree than today,” U.S. Climate Envoy Kerry said at the summit — in Africa and worldwide.

But the global carbon tax will not happen soon — too bad because it could effectively deal with 33 billion tons of annual CO2 emissions. A critical hurdle: Countries manage carbon prices differently. Consider that Europe’s carbon prices are four to five times higher than the United States.

Interestingly, the American Petroleum Institute favors a carbon tax from $35 to $50 a ton. The money collected could reduce the energy cost for low-income households and research and develop cutting-edge technologies. It says this is “the most impactful and transparent way to achieve meaningful progress on the dual goals of reducing greenhouse gas emissions while simultaneously ensuring continued economic growth.”

Talk, Talk, and Talk

BP, Chevron

CVX

XOM

The Global Systems Institute at Exeter says the low-hanging fruit is switching to renewables, which are already cost-competitive with alternative fuels. It’s also electrifying more of the economy, notably transportation. And it’s about saving the tropical rainforests, which are natural CO2 vacuums.

“Finding the financial resources to tackle climate change is increasingly difficult for African countries that are still reeling from the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, now exacerbated by climate change, debt, and inflation arising from a mixture of global geopolitical conflicts and the high global inflationary trends,” said Dr. Akinwumi Adesina, president of the African Development Bank, in African Magazine.

Africa’s first climate summit is a precursor to COP28 in Dubai where negotiators will focus on climate finance. Still, the climate paradox persists, impacting the least developed countries and their economies — specifically in Africa, which is subject to cyclones, floods, and droughts.

Read the full article here