For 25 years, I’ve watched nuclear energy get knocked down and back up — revived mainly because of the need to decarbonize and hit net-zero targets. But this time, it appears that nuclear’s roots in the electricity and industrial sectors will firm up in the next decade and beyond.

That’s irreversible. It’s the only fuel source that can provide round-the-clock carbon-free energy — when we are trying to decarbonize nearly everything, and the electricity demand will probably double by 2050.

“We need to get behind this technology immediately, and it’s a hard reality,” says James Schaefer, senior managing director of Guggenheim Partners, during a virtual discussion hosted by the United States Energy Association in which I appeared. “People need to quickly understand that the current tools don’t get us to clean. Nuclear is safe and clean.”

There are a lot of fundamentals driving that conclusion. However, there are still plenty of hurdles to cross. Investors want to see returns within a reasonable timeframe, not two decades from now: There is an endless regulatory process, unproven technologies, and an immature supply chain. It’s hard to risk billions with so many unanswered questions.

“These projects take a long time to come to fruition,” says Tom Marcille, chief nuclear officer for Holtec International’s small modular reactors unit. “It takes solid financial footing by a company with good financials and adequate cash flow.”

For starters, nuclear will always be more expensive to build than wind, solar, or natural gas. But nuclear units last 80 years, and they are inexpensive to run while they are incredibly efficient. Moreover, the focus must be on nuclear’s cost compared to solar-plus-storage or natural gas-plus-carbon capture.

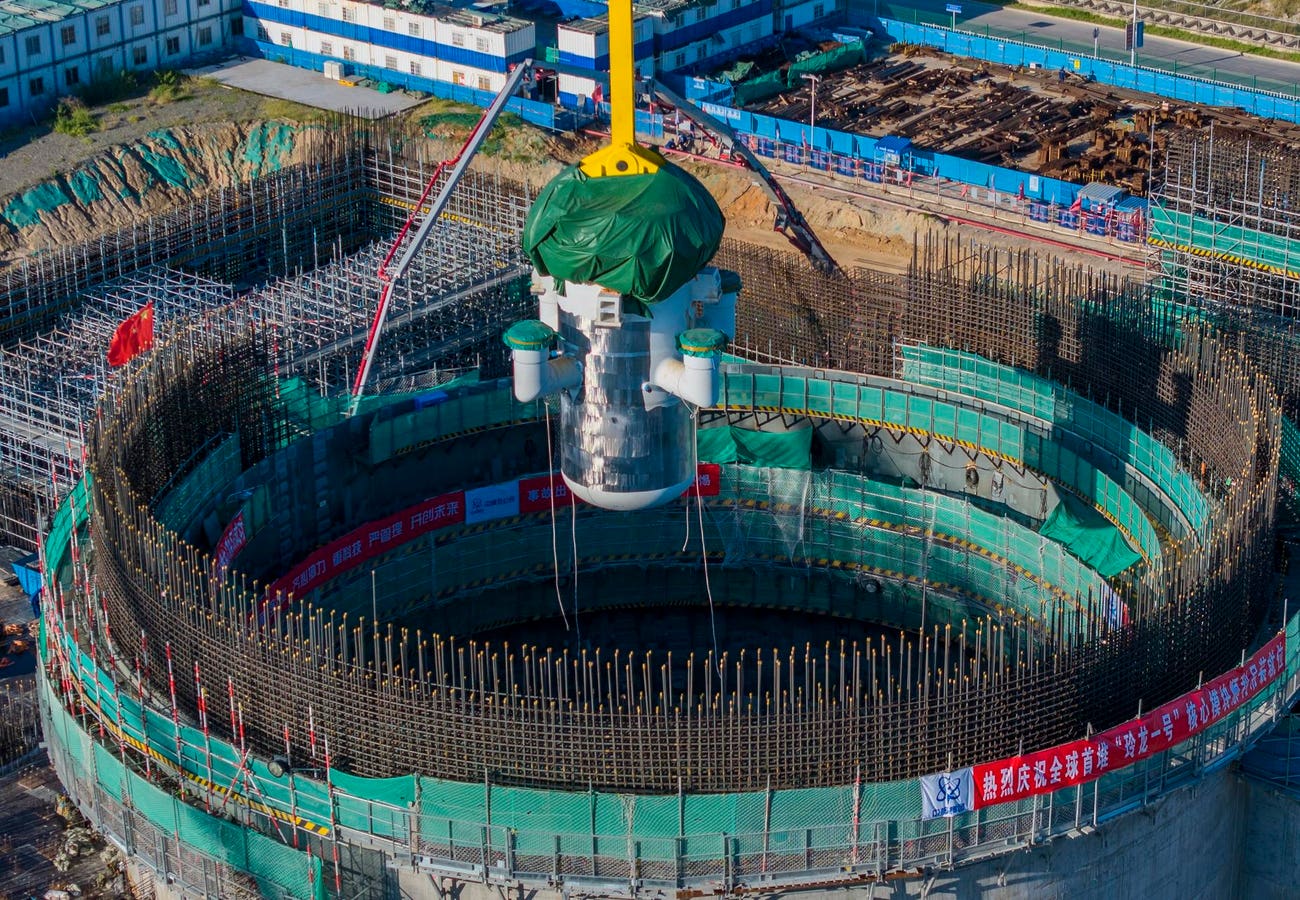

Advanced nuclear designs consisting of small modular reactors will start hitting toward the end of this decade. And once those seeds sprout, a whole garden will form. Allied Market Research says the global demand for those reactors will grow from $3.5 billion in 2020 to $18.8 billion in 2030. That’s a compound annual growth rate of nearly 16%.

Who Is Demanding The Electricity?

For example, NuScale, owned mainly by Fluor

FLR

“We have a very large pipeline,” says Chuck Goodnight, vice president of sales for NuScale. “We’re gonna need that capacity to meet the demand.”

“There’s a natural order of things: if there are signed contracts for real projects, the supply chain will stand itself up. They can confidently make those capital investments,” adds Julie Kozeracki, senior advisor with the loans program at the U.S. Department of Energy, at the virtual conference.

“We are fiercely private-sector-led and government-enabled,” she emphasizes. “So we’ve got low-cost debt financing through the loan programs office — like the 30% and up to 50% investment tax credit from the Inflation Reduction Act. I mean, that’s basically buy one reactor, get one free.”

Back in the day, nuclear-focused utilities such as Constellation Energy

CEG

DUK

For example, Dow is partnering with X-energy to develop a small modular reactor at one of Dow’s sites along the Gulf Coast, which could go live in 2030. Dow is also taking a minority ownership position in X-energy. Each modular reactor can generate 80 megawatts. But they can be stacked together to produce 320 MW, providing clean, reliable, and safe baseload power to support electricity systems or industrial applications.

“The market is a lot larger than ever because industrial members are moving in,” says Steve Chengelis, director of research and development for future nuclear at EPRI, during the event. “The industrial portion of the electrical consumption is about 25% (of CO2 releases,) which is why we will see this mass build-out.”

Can Policymakers Get On The Same Track?

Specifically, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said electric power caused 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions, while industrial operations accounted for 24%. Transportation made up 27%, all in 2020.

But let’s look at another voracious energy consumer — a dynamic that has yet to be considered by long-term planners and adds a whole other layer of complexity to the decarbonization challenge: data centers and artificial intelligence. The International Energy Agency says data centers globally consumed 240-340 terawatt-hours or 1-1.3% of the electricity demand in 2022.

“If you look at a data center focused on artificial intelligence or machine learning, power consumption is typically about five times higher than a typical data center,” says Mark Gake, nuclear technology portfolio manager for Black & Veatch. “So it will drive a lot of extra demand that we must meet. And we’ve got to figure out the right solution, and nuclear should have a stake in that game.”

Elected leaders must coalesce and agree to a long-lasting climate policy to electrify nearly everything. To this end, nuclear energy may provide a bridge between the two major parties. Many elected Republicans are dubious of crafting climate-friendly legislation. Still, they support heavy industry and the jobs those companies create — ditto for carbon-free nuclear power, a significant employer.

At the same time, that thinking comports with the Democratic philosophy and their Keynesian economic views, notes Schaefer with Guggenheim Partners. The government can partner with industry to create jobs and reduce emissions. Many progressives thus welcome such public-private partnerships centered on small modular reactors if they help companies like Dow get clean and hire workers.

Consider: The U.S. Energy Information Administration projects global electricity demand to increase by as little as one-third to as much as three-quarters by 2050. And nuclear energy and renewables will comprise two-thirds of that demand bump.

And that’s why nuclear energy has more than staying power. Indeed, it’s on the road to being a go-to energy source.

Read the full article here