Imagine visiting a doctor who diagnoses you with osteoporosis and prescribes calcium supplements. Months later, you visit a cardiologist who detects calcification in your arteries and advises you to stop taking calcium. It is a sadly common scenario in which siloed experts, failing to consider a system in its entirety, offer solutions that undermine each other and could endanger the whole.

That is precisely what central bankers and government policymakers are doing today. The banks are determined to cure a patient of acute inflation by making capital more expensive and slowing down the economy. Meanwhile, governments need affordable capital and a bustling economy to mitigate climate change, reshore manufacturing of critical goods, expanding housing and re-invest in critical infrastructure damaged by increasingly aggressive wildfires, torrential rains and flooding.

The past 30 years brought us almost continuous low inflation and steady growth as globalization opened borders and allowed countries to capitalize on their competitive advantages. This brought down prices and stimulated higher income and standards of living worldwide.

Today, though, international tensions are fueling calls to control manufacturing and supply chains locally. Onshoring and reshoring are already driving up prices.

Take the onshoring of chip manufacturing, for example. It doesn’t just mean opening a few plants (“fab labs”) in the West. It comes with a demand for specialized engineers and the replication of production processes from countries with relatively cheap labor. It will make chips significantly more expensive, driving up prices for computers, smartphones, TVs, washing machines, electric vehicles, mining tech, agricultural applications and more (because what doesn’t use chips these days?).

Or consider the production of solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles, where China has become the dominant manufacturer and driven down costs tremendously. Try to reshore these industries, and prices will increase.

Put simply, deglobalization drives up inflation and increases labor demand and costs—and will do that for decades because that is how long it will likely take before onshored production reaches parity in cost and efficiency with offshore production. If we clog the arteries of free trade, we will all be worse off.

Practically every important political and economic goal will become much more challenging to achieve with higher capital and labor costs. Inflation is thus likely to stay far north of the central bankers’ arbitrary target of 2% unless we want to gamble with falling into a recession.

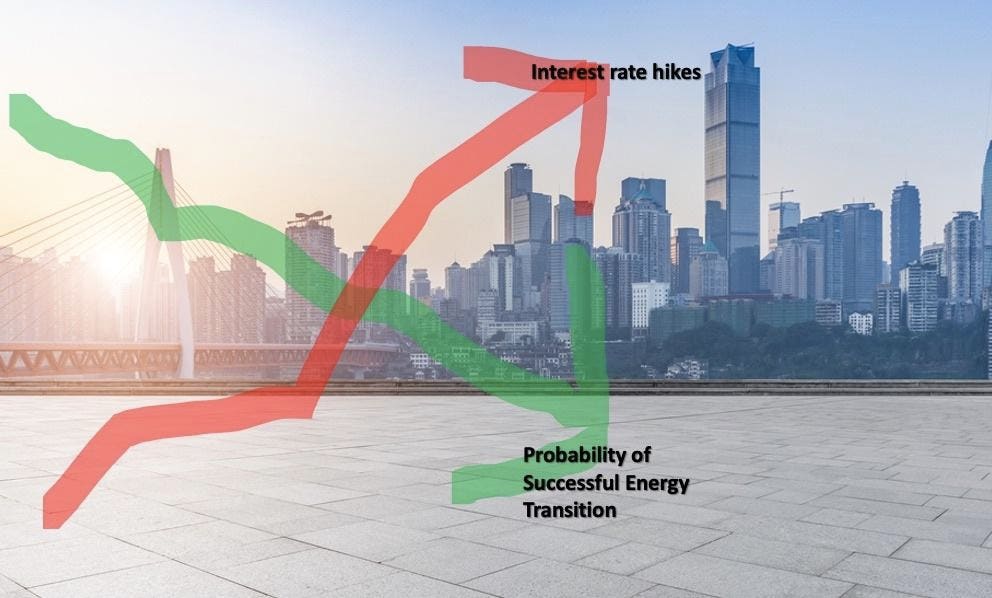

Under today’s circumstances, raising interest rates won’t help to address the root causes of inflation. But it might stall the energy transition. It might perpetuate housing shortages in the Global North. And it may leave us unable to rebuild and future-proof critical infrastructure like power grids, which are buckling under the strains of heat and mass electrification—not to mention damage from climate-related disasters like wildfires and floods.

Ongoing rate hikes will take us towards an avoidable mess. It will hurt the most vulnerable in the society in a world experiencing the highest levels of inequality since the French Revolution (according to a former Governor of the Bank of Canada).

Nevertheless, on July 26 the U.S. Federal Reserve raised interest rates yet another quarter point, while the Bank of Canada did the same on July 12.

Why? When questioned, central bankers fail to adequately explain why the previous rate hikes have not tempered inflation sufficiently, but the next one somehow will. Their tunnel vision is trained on imaginary monetary results and disregards the overall socioeconomic system.

Their old-fashioned remedy of hiking the interest rate until inflation hits 2% will not work today without serious damage to society. Can central bankers not be more targeted? Instead of giving the economy chemotherapy, can they not attack the inflation tumor with precision, in alignment with policymakers and their goals?

Wouldn’t it be better if central bankers had a mechanism for raising interest rates in damaging and high-risk industries—fossil fuels, for example—while lowering rates in clean energy, housing, education and other sectors that are national priorities?

Part of innovation is letting go of old practices that, though effective in their time, no longer serve us. It’s time for a more integrated approach to monetary policy and socioeconomic strategy.

Read the full article here