William Goldring’s Sazerac Company produces some of the world’s most collectible spirits, but it’s the bottom shelf that made him rich. Fireball, anyone?

By Christopher Helman, Forbes Staff

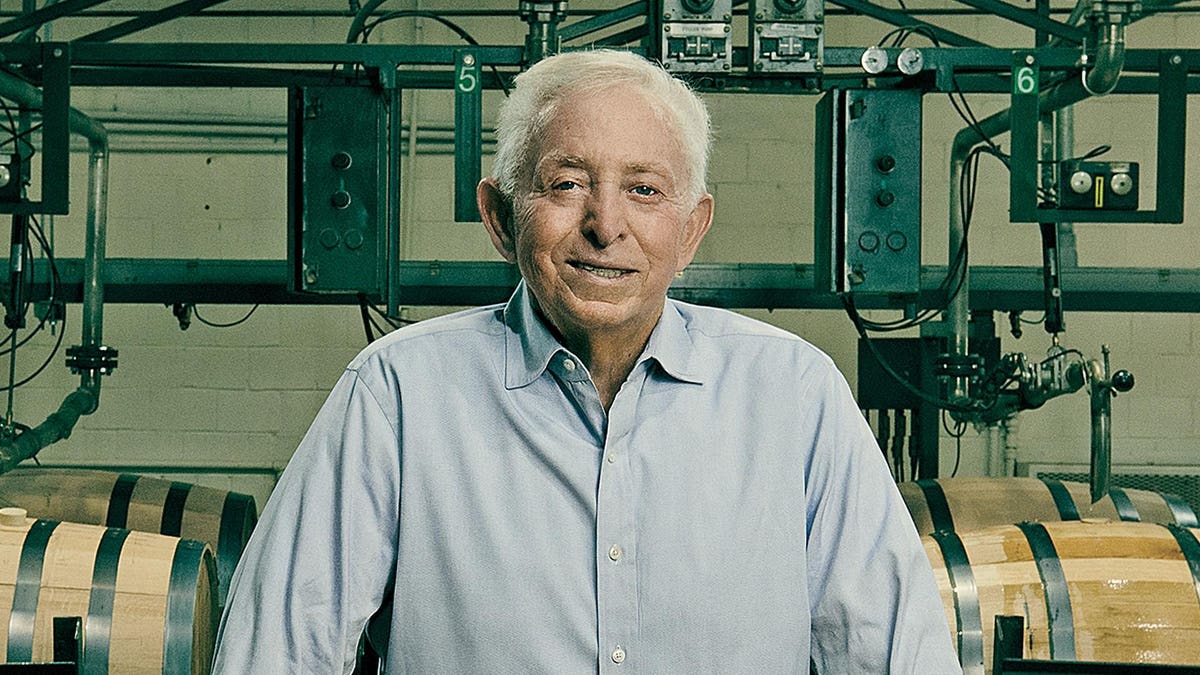

At the top of the hill behind the Buffalo Trace distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky, overlooking what used to be a farmstead, sit 18 seven-story buildings clad in red metal siding. These rickhouses are each filled with some 58,000 wooden barrels, which will yield roughly 18 million bottles of whiskey. And not just any whiskey, but some of the most coveted and expensive bourbon in the world, including Pappy Van Winkle, which, theoretically, costs around $300 a bottle, W.L. Weller ($50) and George T. Stagg ($100)—but good luck finding them at those prices in your local liquor store. Their cost can go up as much as twentyfold on the secondary market.

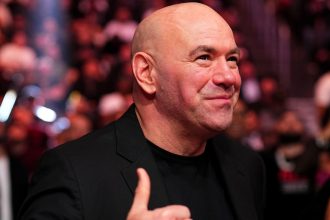

All told, the Sazerac Company boasts 3 million barrels of inventory, which will retail for more than $9 billion once it all comes of age. “My father said, ‘Never go into the bourbon business, because one day you’re going to wake up and have a lake full of bourbon,’ ” laughs the 80-year-old chairman of Sazerac, William Goldring, who debuts on this year’s Forbes 400 with a net worth of $6 billion. “Now we have many lakes.”

Goldring isn’t terribly concerned about selling those lakes. Sazerac markets more than 30 whiskies, balancing sales of super-premium brands with vastly greater volumes of cheaper stuff like Fireball. From almost nothing 15 years ago, Fireball—which is made with younger, cheaper Canadian whisky and tastes like cinnamon Red Hots candies—has exploded in popularity to sell 7.8 million nine-liter cases last year, according to Impact Databank (closing in on Jim Beam’s 11.5 million). All told, Sazerac has rolled up 500 spirits brands and a dozen distilleries in the U.S., Canada, France, Ireland and India. Its share of the U.S. spirits market, at 14% of volume, is second only to Diageo’s. Revenue at the privately held company last year was an estimated $3 billion. “It’s hard to ignore Sazerac,” says Trevor Stirling, a spirits analyst at Bernstein. “They have been impressive share gainers, fueled by Fireball, which is a category killer and still growing.”

Much of the success Goldring has had with Sazerac comes from knowing when to follow his father’s wisdom and when to ignore it. After Prohibition, Stephen Goldring (who died in 1996) started Magnolia Marketing, a liquor wholesaler. To fill holes in his lineup he acquired the Sazerac Company, which made esoteric spirits like Peychaud’s bitters and later Taaka vodka. Young Bill took over both companies in the late 1960s but focused on growing the wholesaler (renamed Republic National Distributing) across 38 states. By the time he sold his stake to joint venture partners in 2010, revenue was an estimated $4.5 billion. “If you’re a distributor, you don’t really own anything,” Goldring says. “I’d rather make the stuff.”

Which is why, via Sazerac, Goldring had been gradually buying others’ spirits brands. The George T. Stagg distillery in Frankfort came first, in 1991. Goldring knew he could sell its 32,000 barrels of aged whiskey. But the distillery (renamed Buffalo Trace) was a mess—“like New Orleans after Katrina,” he says. Production had peaked in 1973 at 200,000 barrels, then fell to 12,000 as bourbon demand evaporated. Goldring couldn’t resist the history: The oldest continually operating distillery (since 1773), Stagg made “medicinal” whiskey during Prohibition. “You can’t plant cut flowers,” he says. “You need roots in authenticity.”

He acquired other venerable bourbons to get access to their fully aged inventory, like W.L. Weller in 1999. Then, in 2002, Sazerac cut a deal with the family of legendary distiller Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle Jr. to bring his wheated bourbon recipe back to life at Buffalo Trace. The cult of Pappy collectors has been growing ever since. A bottle of 23-year-old Pappy Van Winkle sells on the secondary market for more than $5,000.

Unlike, say, vodka, which can be distilled in the morning, bottled in the afternoon and shipped the next day, producing quality whiskey can take decades. “We’re making Pappy Van Winkle today for 2046,” says Sazerac chairman Mark Brown, 66, who has been running the company since the 1990s.

Sazerac’s transformation began in 2009 when it acquired 40 down-market brands for $330 million from Constellation Brands. Suddenly, Sazerac was competing with Goldring’s own wholesale suppliers; the perceived conflict led the Goldrings to sell their family stake in Republic National Distributing in 2010 for what Forbes estimates was $400 million. Goldring flowed cash to a string of deals. In 2016, for $540 million, Sazerac bought brands from rival Brown-Forman, including Southern Comfort. In 2018, for another $550 million, Diageo sold Sazerac Seagrams VO, Myers’s Rum and the gimmicky Goldschläger, which contains flakes of real gold. Insatiable, Sazerac in 2021 picked up Paul Masson brandy from Constellation for $265 million, and last year added the Lough Gill distillery in Ireland for a reported $70 million.

Sazerac currently carries $2 billion in debt, according to FactSet, and generates about $600 million a year in operating profit, per Forbes estimates. All told, Goldring splits an estimated fortune of $6 billion with his wife and three children, and family trusts control 100% of the company.

For all the fancy bourbons, no brand exemplifies Goldring’s top-to-bottom-shelf philosophy better than Fireball, which Sazerac bought from Seagrams in 2000, relaunched in 2007 with a red demon on the label and sells for less than $20 a bottle. Never mind that aficionados turn up their noses at Fireball—the cinnamon spirit boasts a 45% market share among flavored whiskies and scored $1.8 billion in retail sales last year. “It’s a bit of a unicorn,” says analyst Vivien Azer at Cowen & Co. “They have so much scale and leverage already, it helped them organically grow Fireball.”

A value investor, Goldring has parted with only one brand—in 2009 trading Effen vodka to the makers of Jim Beam in exchange for Old Taylor, which was rebranded as premium whiskey E.H. Taylor four years later and named for one of the founding fathers of the bourbon industry. These cult bourbons are not the biggest moneymakers for Sazerac, however, simply because they are produced in such small batches—to support a limited market of spirits that cost hundreds of dollars. Sales are tightly allocated by state.

But they do exert a big halo effect—thus Goldring’s willingness to invest $1.2 billion the past five years to double Buffalo Trace output to 550,000 barrels a year. Vertically integrated Sazerac even makes its own white oak barrels and plants new seedlings. The good news for bourbon lovers: In a few years there will be considerably more 12-year-old Weller, Stagg and Eagle Rare to go around.

Increasingly, however, the most expensive bourbon will be destined for new markets, notably India, which drinks half the world’s whiskey, having been introduced to it by the British. In 2017, Sazerac acquired a controlling stake in the maker of Bengaluru-based Paul John Single Malt and Original Choice whiskies (reportedly for more than $50 million) and plans to grow volume tenfold. It already produces Fireball in India.

While he oversees one of the world’s biggest spirits companies, Goldring prefers to remain under the radar in New Orleans. You might find him at Sazerac House, a museum and bar dedicated to the eponymous spirit and cocktail popularized more than 150 years ago. And what if, as his father warned, tastes change? Goldring shrugs and smiles. “If people stop drinking bourbon,” he says, “we’re up a creek.”

MORE FROM FORBES

Read the full article here