On September 24th, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) commented on Face the Nation “I think we need to re-examine the nature of these sanctions”. She also said that “broad-based sanctions, that punish the overall economy, harm everyday working people and are driving them into the economic and political destitution, that force millions of people, not just to the United States but also to our regional partners, like Colombia”.

Representative Ocasio-Cortez’s remarks came just days after Senator Robert Menendez (D-NJ), a key proponent of sanctions, was indicted on corruption charges. Within Venezuela and across Latin America the mood has also been changing as more political figures agree that broad or sectoral sanctions have worsened the existing economic and humanitarian crisis.

In Venezuela’s neighbourhood, no incumbent president backs the “maximum pressure” policy enacted by the Trump administration. The strategy included sweeping sanctions on Venezuela’s financial and oil sectors, among others, and ceasing to recognise Nicolas Maduro as president. It was led, among others, by Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL), Menendez himself, and ousted IDB president Mauricio Claver-Carone.

The current environment is markedly different from 2019; an alliance of regional leaders formed the “Lima Group” to present a united front supporting maximum pressure. Chile’s President Gabriel Boric, who has always called out human rights abuses in Venezuela and across the region, recently criticised economic sanctions at the UN General Assembly alongside other heads of state.

Representative Ocasio-Cortez is not the first to voice this opinion in Capitol Hill, while it is increasingly held across Washington DC. A congressional staffer mentioned that “many lawmakers recognize that sanctions have been ineffective in achieving political change and have contributed to out-migration, but fear that taking action to lift them will bring backlash for being ‘soft’ Maduro.”

In September 2022, Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT) said that “we are stuck inheriting a policy that did not work, that has in part contributed to a humanitarian disaster that now brings thousands and thousands of Venezuelans to our border seeking salvation”.

Venezuelan investment banker Rodrigo Naranjo argues that broad sanctions are suppressing private activity. As a result, most business leaders are in favour of economic sanctions being lifted. “Many executives I speak to cannot understand why they have to pay for political disputes, between the opposition and the government, and some of which have to do with internal politics in the US.” Adán Celis, the president of Fedecámaras, the largest business union, has also called for an end to economic sanctions.

The Venezuelan government has also been in coordination with four opposition state governors to jointly demand an end to economic sanctions. In the past, opposition leaders played an essential role in giving political cover for the maximum pressure strategy.

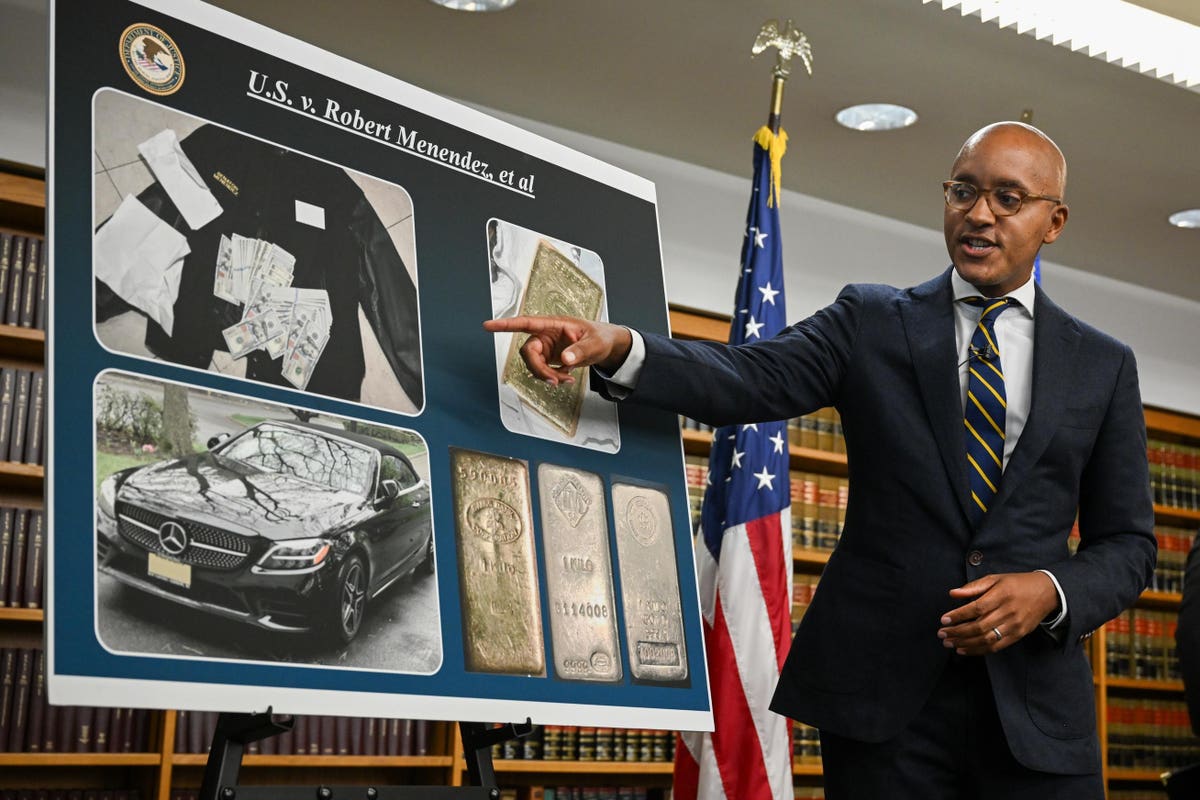

Gold bars and convertible cars

Senator Menendez has been indicted with new corruption accusations. As senate foreign relations committee chair, he had been a staunch proponent of regime change in Venezuela and Cuba, and of broad economic sanctions. He has worked closely with Republican Marco Rubio. He is likely to be replaced by senators Ben Cardin or Jeanne Shaheen, both of whom could work more closely with the Biden White House on this front.

Senator Menendez has been charged for receiving gifts in the form of “cash, gold, a Mercedes Benz and other things of value – in exchange for Senator Menendez agreeing to use his power and influence to protect and enrich [three] businessmen and to benefit the Government of Egypt”.

The timing is key: Menendez was trying to pass through legislation to enshrine sanctions on Venezuela in law. This effort was coming into conflict with White House negotiations with President Nicolas Maduro’s government, as part of a broader deal that could involve democratic guarantees for Venezuela’s 2024 election. The Biden administration is also expected to ease some restrictions on Cuba, “to allow more US financial support of small businesses”.

What happens now with sanctions?

Oil-related and secondary sanctions are likely to go away first. As we reported, the trading ban on Venezuelan bonds is hurting US interests while it hardly affects President Maduro’s position, according to various experts. Nearly a month later, the Financial Times reported a Venezuelan sovereign bond rally as investors increasingly expect a deal in this sector.

Some insiders even argue that economic sanctions policy will be determined by domestic US politics. “Nobody cares about Venezuelans,” said someone with access to Republican and Democrat lawmakers. In their view, whether they are tightened or loosened, it will have more to do with winning over House seats and the Electoral College than human rights.

The idea that US domestic politics determine the outcome of broad sanctions would go against what State Department officials have been saying to the public, under both presidents Trump and Biden. While they were intended to lead to regime change, they are being re-branded as “leverage” to ensure free and fair elections.

Leopoldo López, leader of opposition party Voluntad Popular, argues that sanctions are what brought Maduro to the negotiating table, even if it is yet to show results. “Unfortunately, in the US and Europe energy and migration have taken the main stage, and relegated democracy to the back” said López, when asked about possible sanctions relief. He also said that “sanctions hardly had an effect on Venezuela, if you compare them to the scale of corruption in the country. The collapse of the economy that brought a massive humanitarian crisis and mass migration happened before the imposition of sanctions.”

Michael Paarlberg, political science professor at Virginia Commonwealth University, argues that while the humanitarian crisis started before, “sectoral sanctions relief is one of the few things that the US can actually do to alleviate the humanitarian crisis in Venezuela.” Many opposition representatives are upholding similar positions. Years after broad economic sanctions were imposed –mostly between 2017 and 2019— President Maduro’s position has been consolidated while the humanitarian crisis has worsened.

In the US, and also in Europe, there are increasing concerns that economic sanctions have contributed to the exodus of around 7.7 million Venezuelans and tightening global energy markets. Naranjo said that “while it is hard to quantify just how much of the crisis is due to sanctions or to improper local policies and actions, with sanctions there will be no significant economic recovery that could bring our people back.”

Especially with war raging in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia, European firms are scrambling to find alternative energy sources. Venezuela has vast reserves of oil and gas, but the infrastructure is run-down or non-existent. The Russian ban on fuel exports is bound to exacerbate the search.

While the US is an oil and gas behemoth, the concern is rather that global markets will hit back on the consumer. A source with access to US representatives said “Biden can win with $3 a gallon gas at the pump, but not with $5 a gallon”. It is nonetheless unclear if Venezuela could increase production quickly enough to offset tightening markets before the 2024 race for the White House. Chevron

CVX

Read the full article here