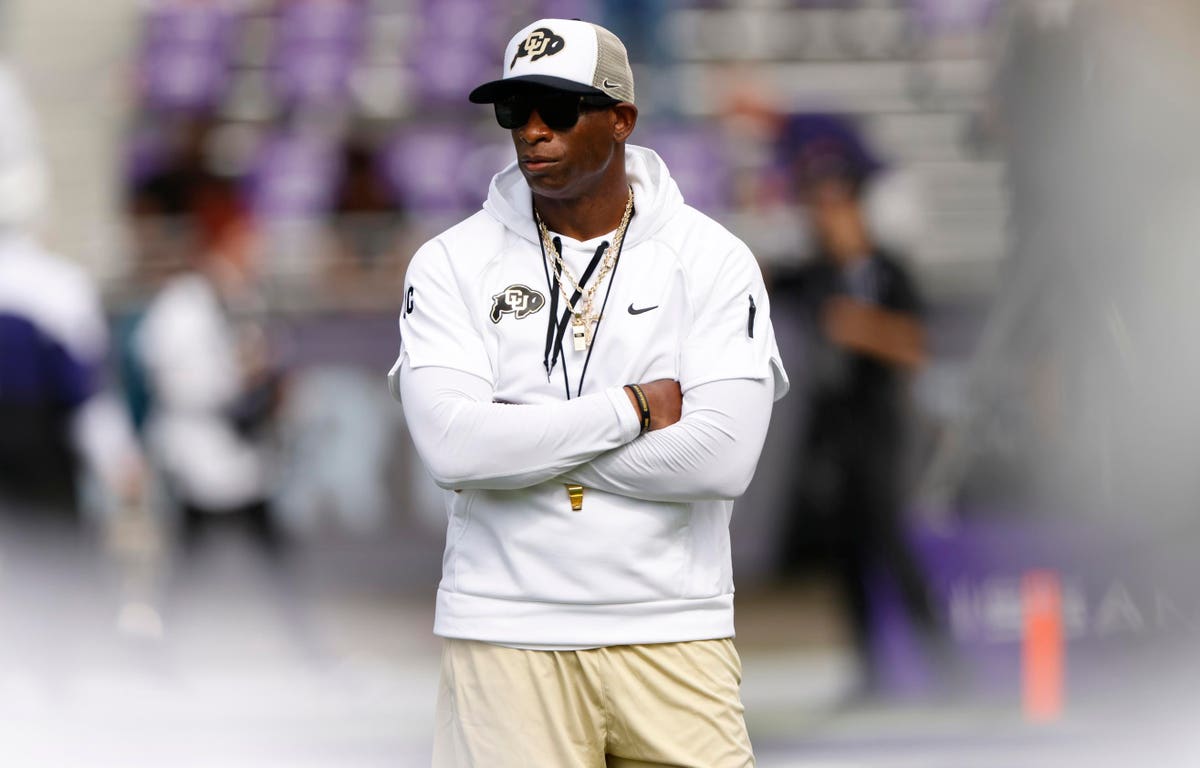

Deion Sanders, aka Coach Prime, has brought winning football back to the University of Colorado and as much as $17 million to the Boulder economy with each sold-out home game, according to the Visit Boulder Convention of Visitors Bureau’s estimates.

Winning is no new feat for Coach Prime. From his Hall of Fame performances in the NFL and the NCAA to his MLB World Series appearance, Sanders has cemented his status as an elite athlete. However, in his second career as a college football coach, he’s making new headlines—both on and off the field.

Coach Prime has begun the season with three straight wins, including an opening-day victory over last season’s NCAA championship runner-up TCU. It’s a dramatic improvement from last season, when Colorado went 1-8. Sanders brought his winning ways from Jackson State, a Mississippi-based HBCU, where he led the team to an undefeated regular season for the first time in the school’s history.

Yet, what’s most impressive about Coach Prime’s new assignment at Colorado isn’t just the wins. It’s his economic impact.

From game tickets to hotel rooms, celebrities to restaurants and merch, the presence of Sanders is driving commerce. Thanks to some verbal jab from Colorado State’s coach, Jay Norvell, Sanders is also selling droves of sunglasses as well.

But why is this happening exactly? It’s more than just a winning team; we’ve seen teams win in the past without this kind of fanfare and economic reverberation. It’s more than just a high-profile professional joining an NCAA football team; we’ve seen this before with Coach Harbough and the University of Michigan, which was greatly celebrated but not as culturally—and, therefore, economically—significant. As a Michigan alum and now professor at the Ross School of Business, that’s hard to admit. But it’s true.

Culture drives commerce. And that’s precisely what Deion Sanders has brought to Colorado: a fuel injection of new meaning that is driving cultural consumption.

Cultural consumption denotes the act of purchasing brands and branded products because of their symbolic value, not just their functional benefits. With Coach Prime, the Colorado Buffaloes aren’t just a football team; they mean something far more now. They symbolize something more than a geography or institution. They are now embodying everything Coach Prime himself stands for. Or, better said, they now symbolize what Coach Prime ‘stands in’ for: confidence.

Sanders is a representation of unmitigated confidence. Everything he exuded on the field and now on the sidelines and in his interviews is a testament to this fact. This associated meaning is being transferred to the team and all that surrounds it—yes, even his sunglasses, which he gifted to all his players. This has become a draw for consumers, a gravitational pull that compels them to want to experience it for themselves. Not because of what it is but because of who they are.

In the 1980s, the LA Raiders were also more than a football team. The team signified toughness, and the brand became a receipt of this meaning. Just about every hip-hop artist of that era who wanted to present themselves as tough, wore LA Raiders gear to project this desired meaning. This was not a designation established only for west-coast rappers. While LA-based artists like NWA certainly wore Raiders gear like a uniform, New York artists like Run DMC and Public Enemy also donned Raiders apparel, not because of the wins and losses of the team, but what the team represented—its cultural meaning.

They, too, participated in the cultural consumption of the brand because of what it signified.

Like the 1980s LA Raiders, who signified toughness, Colorado has new meaning and now operates in a new context. It’s not just a football team; the team is evolving to signify confidence—showtime style—right before our eyes. The economic impact of such cultural framing moves the brand beyond what it does to what it stands for, transcending the category to be more than just a product.

We saw this on display all summer with the musical tours of Beyoncé and Taylor Swift, both artists who have transcended their genre to stand for something far more significant than performers. They both represent a unique brand of feminism. Like any good brand, they both stand in for something else, signifying something more than just artists who sing songs and perform. They have moved beyond the category to represent an idea.

The economic impact of this transcendence has been significant. According to reports, Beyoncé and Taylor are estimated to generate billions in spending. Together with the Barbie movie, another signifier of feminism, the pair have created an economic boom, contributing 0.5 percentage points to the national GDP. Anytime your economic impact is quantified by it’s relationship to a country’s GDP, you know you’ve done something significant.

Barbie fans bought pink ensembles. Swifties drove sales at Michael’s retail stores to purchase materials to make their Eras Tour friendship bracelets—a cultural artifact for her community of fans. To celebrate Virgo season, her birth sign, Beyoncé instructed fans—the Beyhive—to wear silver to her shows, which drove a sales uptick for the online retailer Etsy as fans scrambled to meet the aesthetic expectation of the community. Their collective meaning-making influenced consumption, which then propagated into the population more broadly.

This has less to do with the products and more to do with their cultural meaning. Culture is a meaning-making system, not a popularity barometer. Culture is the way by which we translate the world, and this translation informs what people like us do and, ultimately, consume.

People aren’t buying Coach Prime’s sunglasses because of their features, or even because of Coach Prime himself, no more than people bought Ray Ban sunglasses because of their function or Will Smith telling us, “I make these look cool,” in the 1997 blockbuster movie Men In Black.

Like Smith, Coach Prime has given these particular sunglasses—and the University of Colorado, for that matter—new meaning. And those who have decided to consume these glasses—and join the Colorado fandom—have done so as a strategy to pursue their own identity projects. That is to say, they use these branded products to signal the meaning they want to project about themselves—confidence—because the meaning associated with the brand is congruent with their ideal conception of self.

Like Swifties, the BeyHive, Barbie, and the LA Raiders, our consumption is a way by which we make our culture material. This is only possible when the product transcends the category to signal meaning beyond the value propositions and functional benefits and says something about ourselves that our words could never do as saliently as the branded products we don.

But it’s not Deion Sanders himself that’s the influence at play; rather, it is our shared understanding of what these branded products now mean to us that establishes the compelling proposition and the invisible forces of culture that persuade us to consume—to buy, to watch, to join the discourse, and the like. This doesn’t happen because of a catchy tagline and eye-catching iconography.

Instead, this is a byproduct of culture as a mediator of meaning and an influential force of normality. The better we understand it, the more likely we are to leverage its influential power. The less we understand it, the more likely we are to be influenced by it.

The choice is yours.

Read the full article here