Contributing Author: Lawrence Iser

The recent news that Chris Rock will be producing and directing a film about the life of Martin Luther King Jr. raises interesting questions regarding the legal rights and clearances that must be acquired to undertake such a production. The answers to these questions also explain the scarcity of films about the legendary Dr. King.

In 2009, iconic filmmaker Steven Spielberg and his company DreamWorksSKG successfully negotiated with Dr. King’s Estate to obtain a license to use Dr. King’s copyrighted speeches in a film, and news broke that Spielberg had also obtained the film rights to Dr. King’s life (known in the movie business as “life rights”). By paying the Estate for the film rights to Dr. King’s speeches along with life rights, Spielberg obtained unprecedented filmmaking access to Dr. King’s life — supported by Dr. King’s extraordinary intellectual property (the right to use Dr. King’s actual words). At the time, NPR quoted a DreamWorks press release stating “The DreamWorks film will be the first theatrical motion picture to be authorized by The King Estate to utilize the intellectual property of Dr. King to create the definitive portrait of his life.” Although the DreamWorks project was eventually canceled, Spielberg held onto the copyright and life rights licenses.

It was reported this week that Universal Pictures had optioned the rights to adapt Jonathan Eig’s acclaimed biography King: A Life, and had joined with Spielberg (who will executive produce) and Rock (who will produce and direct) to collaborate on what they hope will be the “definitive cinematic biopic about the life of Dr. King.”

The executors of Dr. King’s Estate—his children Bernice, Dexter, and Martin— have been understandably cautious about licensing the rights to their father’s works. The Estate has chosen carefully among potential projects, at times realizing significant sums for use of Dr. King’s works, while declining other requests. At the same time, the Estate has zealously guarded the marketplace for non-licensed uses, including suing USA Today, CBS and PBS

PBS

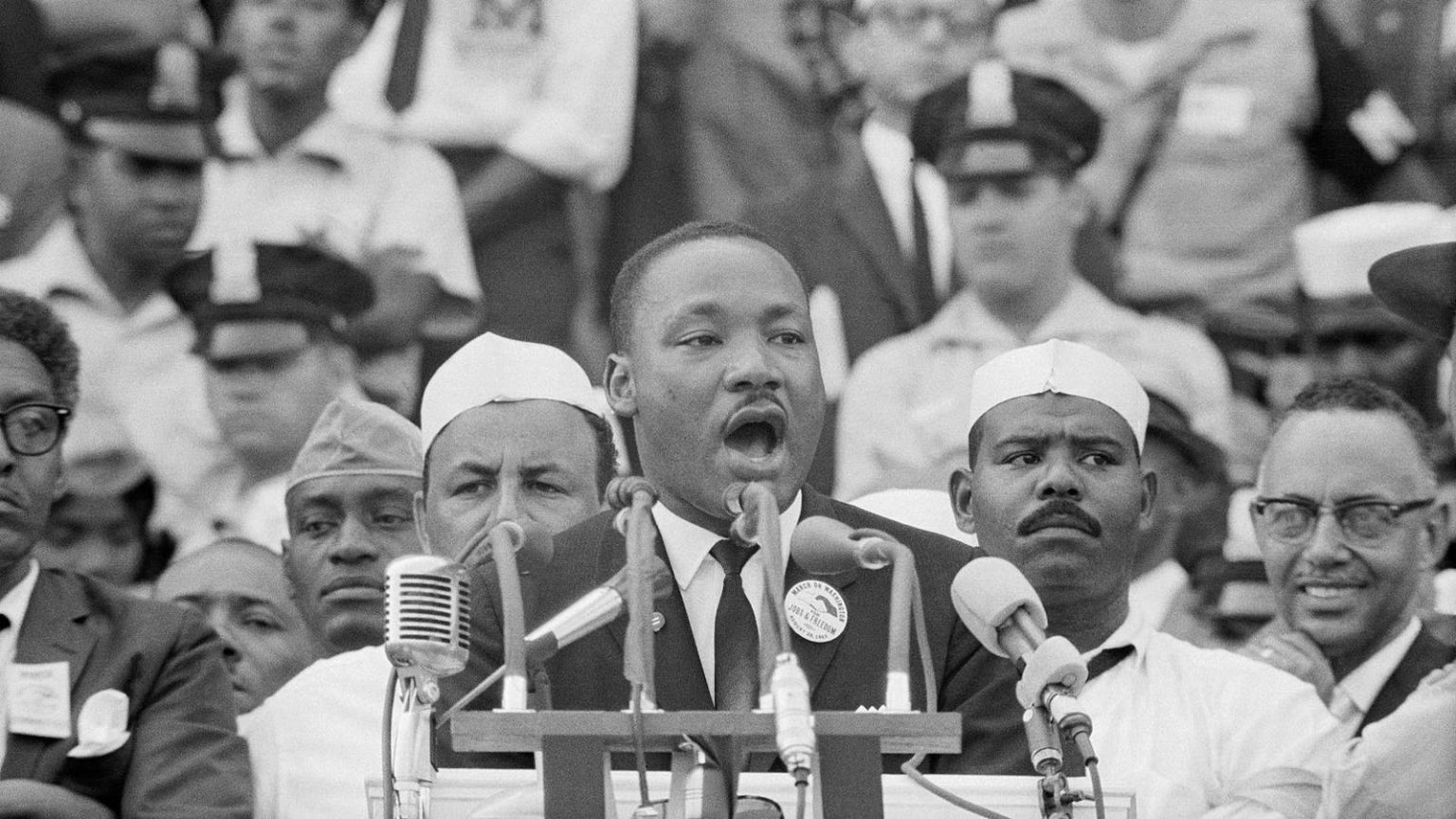

The Estate’s actions appear to be consistent with Dr. King’s wishes, who prudently obtained copyright protection for his brilliant speeches. It was totally appropriate for Dr. King to obtain copyright protection. As a brilliant writer and orator, his spoken word was equivalent to other creative works typically protected by copyright such as songs, sound recordings, books, photographs and films. And like any other copyrighted work, Dr. King had the exclusive right to exploit his oratory, to benefit financially from his creativity, and to prevent the unauthorized copying of his speeches. As one example, after delivering his “I Have a Dream” speech in August 1963, King obtained a preliminary injunction enjoining record companies Mister Maestro and 20th Century Fox from selling recordings of the speech. Dr. King proved in court that he had protected his copyright by permitting only limited distribution of copies of his speech to the press covering his famous march on Washington, but not to the public.

Interestingly, the restriction on using King’s copyrighted speeches came into view with Ava DuVernay’s 2014 film Selma. DuVernay wrote soliloquies for lead actor David Oyelowo to perform that sounded like they could have been King’s actual famous speeches, but they were actually paraphrased, since DuVernay did not have the rights to use King’s actual words (indeed rights to the actual speeches had already been licensed to Spielberg). However, Oleyowo’s performance moved Spielberg so much that he reportedly asked Oyelowo if he would reprise the role in his film. It has not yet been announced whether Oleyowo will be part of Rock and Spielberg’s upcoming film.

The bottom line is that no one may use Dr. King’s speeches in a film or television show, or for any other purpose, without first obtaining a license from the Estate – as Spielberg has. Although Hollywood typically obtains an additional “life rights” license to portray a famous person in a film, as Spielberg did to secure the cooperation of the King Estate, no such license was actually necessary because of the broad latitude given filmmakers under the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution to portray famous persons in film. To be sure, a company that wants to produce MLK merchandise, such as t-shirts and lunch boxes, would need a license from the Estate of what are known as “publicity rights.” However, a filmmaker is not required to obtain a “life rights” license to portray a famous period in a film.

The King Estate has been consistent in its approach over the years. The reason you often do not see the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech in its entirety outside of protected educational and news uses, but instead only short excerpts, is that excerpts are less expensive to license (occasionally, networks including CNN have reportedly obtained licenses from the King Estate to air the entire speech). And certain limited uses of excerpts of Dr. King’s speeches (such as educational uses) may well be protected under copyright’s fair use doctrine. While it may seem strange that such a historic speech isn’t readily available to the public, this was Dr. King’s prerogative.

As such, the collaboration among Rock, Spielberg and Universal could only be accomplished with the valuable rights obtained from Dr. King’s heirs.

Lawrence Iser is a Los Angeles entertainment and intellectual property attorney, who has been repeatedly named to the Billboard list of “Top Music Lawyer,” to Variety’s Legal “Impact” report, and a Hollywood Reporter “Power Lawyer.” His clients include Mattel

MAT

Read the full article here