Let’s debunk some of the myths around this buzzy new technology.

Don’t be fooled. The innovation that is lab-grown meat — or “cultivated meat” as industry insiders have decided to call it — is not the great entrepreneurial success story of the next generation. Investors want you to believe otherwise, and though they have a right to feel giddy that last week U.S.-based startups Good Meat and Upside Foods got the nod to go to market from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration, a variety of factors will hinder the adoption and growth of no-kill meat. Not least of which is the cost: in the past five years, billions of dollars have been spent on developing the 100-plus startups in the industry. They will need billions more.

The sector “needed a huge shot in the arm for them to be able to say not only are we progressing, but we’re progressing in one of the most challenging aspects of bringing this to market, which is the regulatory,” investor Lisa Feria, the founder of Kansas City-based Stray Dog Capital, tells Forbes. “The scale-up piece still remains as a big, huge, very costly part of bringing this to market.”

Here are some factors that demonstrate what a long journey it will be from regulatory approval to the dinner plates of the average American family.

Prices are high but not high enough to turn a profit. Lab-grown meat costs thousands if not hundreds of thousands per ounce to produce. Brands, however, have decided to take substantial losses so that the prices of cultivated-meat dishes are in line with the ordinary cud-chewers and feed-peckers customers are used to. The first dishes of Upside’s chicken will pop out at chef Dominique Crenn’s Michelin-starred Bay Area restaurant Bar Crenn, while Good Meat will sell in Washington, D.C. at chef José Andrés’ China Chilcano — prices to be determined. Andrés owns shares and Crenn has a multi-year deal, but they don’t want customers’ heads to explode when they look at the right side of the menu. Expect a normal entree price. Expect big losses.

Lab-grown meat may never make money. The artificial price points — justified because giving a taste to as many people as possible is good business — could ultimately hurt the brands. The cost structure is expected to be out of whack for years, if not decades, and many of the folks trying lab-grown meat now for the first time may never see a time when the products are profitable.

“Profitability is very much years off because the biggest challenge ahead of them is can we make it at millions of tons a year and ultimately remotely compete with conventional meat,” says Feria, who backs Upside Foods as well as a host of its competitors, and predicts that a lot of startups will eventually merge or be acquired by large meat companies like Tyson and JBS.

Cultivation ain’t cheap. To produce lab-grown meat, manufacturers use what’s called a bioreactor — the same machinery drug companies use to make vaccines. They’re expensive and have long waitlists. Also costly is construction of the factories in which to put the bioreactors. Good Meat CEO Josh Tetrick says a facility able to produce 30 million pounds of cultivated meat would cost as much as $650 million. Feria says one of the startups in her portfolio recently estimated its facility would cost, conservatively, $450 million. Investors will have to continue to dig deep.

Will it taste like chicken? Feria says she advises anyone who’ll listen not to rush their novel foods to market. “It’s going to really impact the category, what products people put in their mouths first,” she says. “Those products need to be impeccable. I want people to be wowed.”

Cultivated meat is not necessarily good for the environment. It’s true that the traditional methods of bringing meat to market drive irreversible climate change, but lab-grown meat presents a slightly different problem: it sucks up a massive amount of energy. There’s not a lot of research on that, especially the kind not funded by startups or their industry associations. That said, a few recent studies have shown that there’s cause for concern. The alt-protein industry’s Good Food Institute has most recently claimed that in a decade, lab-grown meat could have a smaller environmental impact compared with conventional cattle production, if renewable energy is used. Their study estimates roughly 80% fewer carbon emissions, in addition to less land gobbled up. But if cultivated meat uses traditional energy sources at scale, a 2015 study found that it would be worse for the planet than conventional meat production. In another paper, published last month, researchers found that the environmental impact of lab-grown meat could be 4 to 25 times worse than the average beef sold at supermarkets.

Of course, the industry could adopt renewable-energy sources, but most factory plans rely on tapping into the national energy grid, which is already oversubscribed and meant foremost for public infrastructure and not a business that may never be profitable.

Lab-grown meat isn’t especially healthy to eat. Experts say the cultivated proteins could be defined as ultra-processed, which the National Institute of Health and United Nations researchers have warned against for years. Some studies even show links to cancer and other diseases with certain kinds of ultra-processed foods. It’s too early for any research on the long-term impacts of eating novel proteins, or the effect of using a sterilized environment to create nutrients for people to consume.

Besides, the amount of money investors are pouring in doesn’t incentivize taking things slowly and doing things intentionally, Adrian Rodrigues, a Washington-based investment banker who founded Provenance Capital, tells Forbes. “That puts a lot of pressure on the amount of concern there is prioritizing the safety of the product and ensuring that there’s not just short-term testing, but longitudinal testing,” Rodrigues says.

Patent wars loom. Plant-protein pioneers Impossible Foods and Motif FoodWorks have been locked in a prolonged (but not bloody) battle to determine who has the right to make non-meat burgers a certain way. The same could easily happen in the no-kill space. Each startup has its own proprietary formula. Some are backed by patents. Others are trade secrets. Rodrigues calls the lab-grown startups “hyper-invested companies that seem to be focused on an intellectual property grab, to really give a foundation to intellectual property-focused returns.”

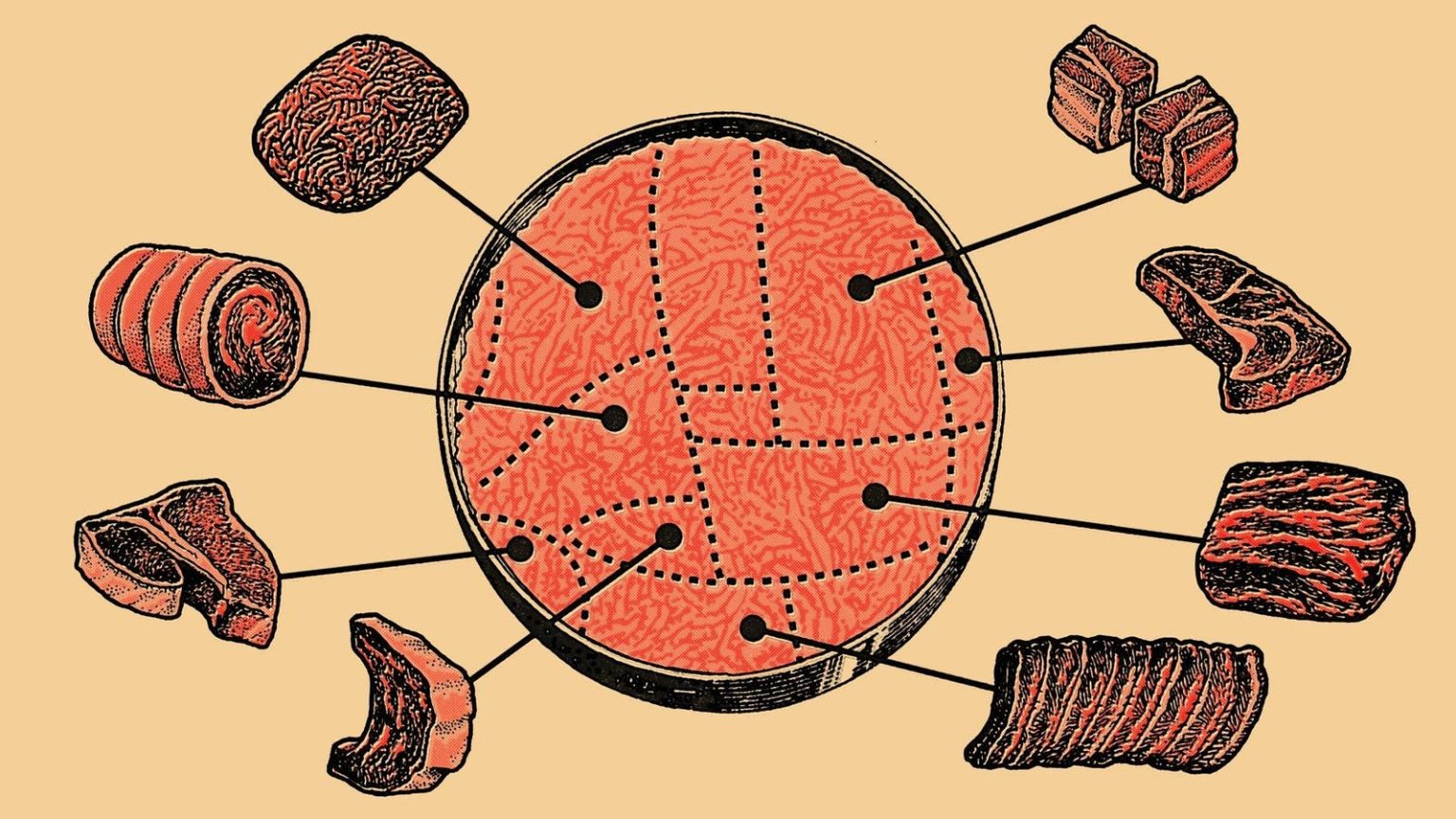

Lab-grown meat does nothing to address economic problems around food. Forty million Americans don’t get enough to eat, and lab-grown meat won’t do a thing to lighten their burden. The price to produce the food is too high, and it may never come down enough. That means investors are targeting only the super high-end versions of lab-grown meat, like no-kill ribeyes, tenderloins and lobster tails that will sell for more than ordinary fare such as chicken nuggets or burgers. The vast majority of people wouldn’t spend $50 on a lab-grown burger, but some of them might be persuaded to spend that on a ribeye. That means this technology is being funded and scaled up mostly for the consumption of the wealthiest. Let the 40 million eat lab-grown cake.

MORE FROM FORBES

Read the full article here