In 1767, as American colonists’ protestations against “taxation without representation” intensified, a Boston publisher reprinted a book by a British doctor seemingly tailor-made for the growing spirit of independence.

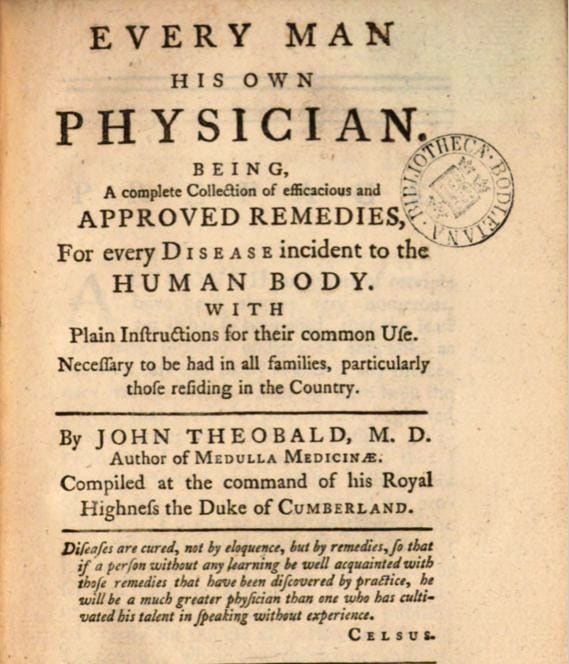

Talk about “democratization of health care information,” “participatory medicine” and “health citizens”! Every Man His Own Physician, by Dr. John Theobald, bore an impressive subtitle: Being a complete collection of efficacious and approved remedies for every disease incident to the human body. With plain instructions for their common use. Necessary to be had in all families, particularly those residing in the country.

Theobald’s fellow physicians no doubt winced at the quotation from the 2nd-century Greek philosopher Celsus featured prominently on the book’s cover page.

“Diseases are cured, not by eloquence,” the quote read, “but by remedies, so that if a person without any learning be well acquainted with those remedies that have been discovered by practice, he will be a much greater physician than one who has cultivated his talent in speaking without experience.”

Translation: You’re better off reading my book than consulting inferior doctors.

To celebrate Americans’ independent spirit, I decided to compare a few of Dr. Theobald’s recommendations to those of his 21st-century equivalent, “Dr. Google.” Like Dr. Google, which receives a mind-boggling 70,000 health care search queries every minute, Dr. Theobald also provides citations for his advice which, he assures readers, is based on “the writings of the most eminent physicians.”

At times, the two advice-givers sync across the centuries. “Colds may be cured by lying much in bed, by drinking plentifully of warm sack whey, with a few drops of spirits of hartshorn in it,” writes Dr. Theobald, citing a “Dr. Cheyne.” Dr. Google’s expert, the Mayo Clinic Staff, proffers much the same prescription: Stay hydrated, perhaps using warm lemon water with honey in it, and try to rest. Personally, I think “sack whey” – sherry plus weak milk and sugar – sounds like more fun.

Dr. Google sensibly advises treating a sprain by applying ice to it. In Dr. Theobald’s time, when the absence of reliable refrigeration meant ice wasn’t always available, a remedy attributed to “Dr. Sharp” was both more complex and fragrant: “After fomenting with warm vinegar, apply a poultice of stale beer grounds, and oatmeal, with a little hog’s lard, every day till the pain and swelling are abated.”

In Every Man His Own Physician herbal remedies abound. To remove warts, for example, Dr. Theobald, citing “Dr. Heister,” recommends “rubbing them with the juice of celandine.” Surprisingly, Dr. Google agrees. A search for “celandine” and “warts” quickly unearths an article in a public health journal concluding that celandine can, indeed, cause viral dermal warts to disappear.

Even more unexpected is what at first glance seems sure to be a spurious claim about cancer. Dr. Theobald writes that “Dr. Storck of Vienna greatly recommends the use of hemlock in cancerous cases and gives several surprising instances of its success.” Shockingly, Dr. Google essentially agrees, revealing that ground hemlock contains paclitaxel (Taxol), used as a chemotherapy drug.

But just like excessive Googling can be hazardous to your health, so, too, can Every Man His Own Physician. “Head-Ach”? Attributed to “Dr. Haller,” we get this remedy: “Apply leeches behind the ears and take twenty drops of castor in a glass of water frequently.” Aspirin, anyone?

Similarly, while acknowledging that diabetes cannot always be cured, Dr. Theobald’s prescription, taken from “Dr. Mead,” gives pause: “Take of the shavings of sassafras two ounces, guaiacum one ounce, licorice root three ounces, coriander seeds, bruised, six drachms; infuse them cold in one gallon of lime-water for two or three days, the dose is half a pint three or four times in a day.”

As recounted by historian Gordon Wood in The Radicalism of the American Revolution, one consequence of the nation’s revolutionary success was a growing sense that ordinary people could not trust elites. In an analysis that sounds uncomfortably familiar, Wood writes that assaults on elite opinion and the celebration of “common ordinary judgment” resulted in a dispersion of authority in which knowledge and truth “had to become more fluid and changeable.”

While we should certainly celebrate the type of democratization of medical information symbolized by Every Man His Own Physician (which would be reprinted for decades), as well as the online information outlets available today, availability does not guarantee reliability. As with democracy itself, where the people and their leaders need to see themselves in a partnership, a trusting doctor-patient partnership remains crucial.

Read the full article here