Today software does not come with information labels that clearly says what you’re about to use in standard, simple language. But what if it did? Regulators use nutrition labels to prevent false advertising and promote food safety. We have an opportunity to re-think health technology labeling to rebuild trust and help people make better choices. Imagine if the new wave of generative artificial intelligence (AI) products had clear labels to engage the public about risks and benefits. Perhaps some of the issues from the recent OpenAI board coup and governance concerns could have been addressed using adequate education and warnings.

For more than 80 years, the United States has required some form of label on foods and drugs to ensure that consumables are safe. This year, in fact, marks the 33rd anniversary of the act mandating national food nutrition labels.

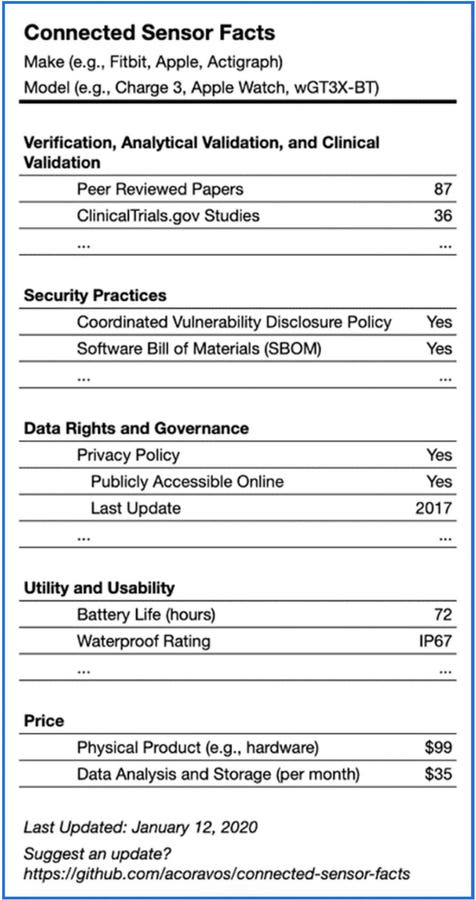

Recently tech companies have started to realize the importance of having similar labels for fitness trackers and other products that straddle the increasingly thin line between consumer gadgets and medical devices.

Fitness trackers and their associated algorithms share many similarities with the highly-regulated world of medicine and prescription drugs, including the possibility for “side effects” that produce inaccurate data in under-represented populations, according to experts. When considering complex products for which users have to make difficult risk-benefit decisions, labels are simply essential.

What labels could look like

Flip around a cereal box to the nutrition labels and notice what grabs your eyes. Perhaps it is the amount of sodium. Or maybe the daily value percentage of protein or iron and other key nutrients.

HumanFirst CEO and co-founder Andy Coravos teamed up with researchers from Duke, Sage Bionetworks, and Mount Sinai to publish an article in Nature npj Digital Medicine that considered elements that would be relevant to evaluate the risks and benefits of using a mobile, connected, sensor-derived digital health technology (DHT).

A mobile device can detect certain physiological metrics like heart rate, body temperature, and movement and upload data to a personal account. Connected medical devices like mobile electrocardiograms (EKG) to detect heart arrhythmias are becoming home use consumer products. A consumer might value the company’s health data encryption and cloud security practices over battery life. Today, there is no good way of benchmarking these various metrics the way a nutrition label shows food trade-offs such as calories versus proteins.

Studies suggest that simple, readable labels give consumers more confidence in the products they use – alongside a higher willingness to pay for products rubber-stamped with trust-based labels. One United Kingdom government report found that three-quarters of respondents felt that it was important to introduce labels for privacy and security in smart devices.

There have been some proposals for companies to put labels on devices in order to give users a clearer sense of their privacy practices. This includes applying for a Trusted Technology Mark that is only given to products that reach a certain threshold with respect to data rights, security, and transparency. Apple announced that apps in its store will have to include nutrition labels for privacy.

In the technology culture defined by moving fast and breaking things, there’s clearly an appetite to develop these sorts of labeling systems. We can shift to a move fast, and fix things mindset with better tools and transparent systems. In spring of 2021, Duke researchers drafted Model Facts labels built off concepts pioneered by researchers at Google, Dartmouth and the FDA – to help doctors determine when and how to use machine learning models for clinical decisions.

Some efforts move even further up the pipeline from the algorithms to the source data. Harvard and MIT researchers collaborated on the Dataset Nutrition Label Project to measure the completeness and inclusiveness of datasets.

This year Twillio unveiled an AI Nutrition Facts label generator to give consumers and businesses a more transparent and clear view of ‘what’s in the box’ and how their data is being used.

How consumers could use health tech labels

Scenario 1: You are a consumer that may have sleep apnea. While examining a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine that fits your budget, you also want to find a device that is lightweight to allow for travel and shares data recording to your phone. You review the “nutrition” labels of CPAP devices and pick one that best meets your criteria.

Scenario 2: You are a Principal Investigator setting up a new decentralized clinical trial protocol for a psychedelic medicine to treat severe PTSD, following the clinical data that MAPS recently published in Nature. You’re thinking about your REMS program and are looking to evaluate the risks and benefits of various remote monitoring products. For some patients a wearable that collects their data all the time could be scary and they worry about being constantly watched and tracked. On the other hand, a well-designed wearable can provide a sense of safety and security for these trial participants.

Scenario 3: You’re an executive in a biopharma company. You want to collect measures that matter to patients such as I could walk up stairs or I slept better. Collecting quality of life and performance outcomes using sensors (and using labels to evaluate quality ones) could change the way clinical trials are conducted. Over 130 pharma and biotech sponsors have collected digital endpoint data to submit to regulators. Using labels could help move towards a more convenient approach to drug discovery and development.

HumanFirst’s Atlas is primarily built for pharma and biotech teams to design and deploy more effective precision measurements in clinical trials. The company curates around usability, data privacy and security Such information could begin to be used to develop health tech labels that would be more widely leveraged by consumers and physicians for personal care. While there’s still a need for education to empower consumer decisions, centralizing the information objectively and without bias to empower choice is the first step.

As we evaluate novel digital tools we can pull lessons from the drug and food industries in order to increase confidence in healthtech. We can learn how to document and share adverse events such as detecting and reducing algorithm bias, and better information can help consumers make decisions on how to best use products. Well-designed labels can assist with all of these aspects to build a more human-centric healthcare infrastructure.

Read the full article here