The Medicare program’s “value” payments don’t sync with what Medicare beneficiaries most value, a new study shows, creating an uncomfortable policy challenge.

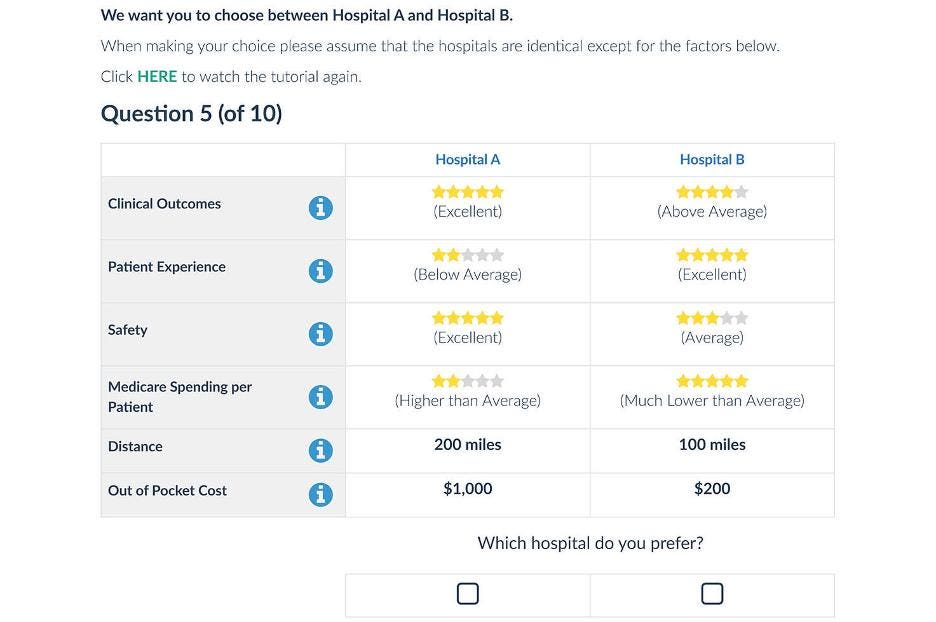

The study in JAMA Network Open involved more than a thousand Medicare beneficiaries shown a carefully designed comparison of two fictional hospitals, with their differences displayed in a simplified version of the star ratings system on Medicare’s Compare website.

The six hospital characteristics that were shown – clinical outcomes, patient experience, safety, Medicare spending per patient, travel distance and out-of-pocket cost – paralleled the four quality domains of Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program (HBVP). Those domains are clinical care; person and community engagement; safety; and efficiency and cost reduction.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) weights each domain equally when it pays hospitals enrolled in the HBVP program, but the patients whose lives were at stake felt very differently. Not surprisingly, they cared most about leaving the hospital healthy and alive. Researchers showed that a high rating for “clinical outcomes” was by far the most important factor in choosing a hospital, followed far back by safety and patient experience, which each got a bit less than half the statistical weighting of “clinical outcomes.” “Efficiency” scored lowest, about one sixth of clinical outcomes.

The authors cited the PhD thesis of Cynthia Barnard (personal disclosure: a friend and colleague) as an accurate characterization of Medicare’s value-based payment system being a provider-centric model “without having meaningfully explored the patient’s priorities.”

The researchers acknowledged that Medicare has to be concerned with efficiency, given limited resources, but they explored what would happen to hospital payments if Medicare listened to its beneficiaries. The answer, it turns out, is “Not much.”

Despite pervasive rhetoric about moving from “volume to value,” HBVP payments constitute a mere two percent of hospital reimbursement, which, research suggests, is likely why there’s limited evidence the program has improved quality. Just $86 million would be shifted around, a tiny tenth of one percent of the HBVP program’s total cost, according to the study’s simulation involving the nearly 3,000 hospitals in the HBVP program.

Small as that number is, however, the impact would be unevenly distributed, with money being taken away from smaller, more rural hospitals serving less-complex patients and flowing to larger, high-volume hospitals.

And that’s where the policy challenge emerges.

The authors conclude that the redistribution of funds could “exacerbate disparities” in care, which they connect to a concern for “equity.” That language, however, is somewhat misleading. These aren’t “disparities” related to racial or ethnic factors, but reflect actual differences (disparities) in care quality. Yet with nearly 30 percent of the rural hospitals nationwide at risk of closing in the near future, according to a report earlier this year, policymakers still face a tough choice.

Changing value-based payment system to reflect seniors’ values risks replacing less-than-stellar care by some rural hospitals with better care available only by hospitals so distant as to be practically inaccessible. In addition, small hospitals play a vital role in community economic health, an issue of intense interest to the elected representatives of those affected.

My guess is that the policy question and the political one both argue for a firm policy of inertia: “First, do no harm.”

Read the full article here