Is the housing shortage merely awful, or jaw-droppingly catastrophic? Depends on who you ask. The Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies estimates that there’s a deficit of 1.5 million dwellings. Realtor.com says that we’re 2.3 million units short. Zillow says it’s 4.3 million, and the National Association of Realtors (NAR) guesses we’re shy 5 million to 6 million homes.

The Biden administration recently announced several programs to goose the construction of affordable housing. The efforts won’t situate everyone into a decent place that they can afford to rent or buy. But over the next few years, the programs could ease housing burdens for hundreds and maybe thousands of households.

The problem is that the federal government is engaging the situation with a polite nudge when true progress requires a rude shove. If Congress would increase funding and the White House would apply more imagination, the impact could be bigger.

Two main causes for the housing shortage

In five years, the median resale price of an existing home went up 51%, to $406,700 in July 2023, according to the NAR. Prices are too high for many would-be buyers. In early 2022, Freddie Mac

FMCC,

polled Gen Z adults (ages 18 to 25 at the time), and 34% of them agreed that “homeownership at any point seems out of reach financially.” Mortgage rates have zoomed since that poll was conducted, making homes even more unaffordable.

More: Mortgage rates reach highest level since 2001 and are likely to go higher, Freddie Mac says

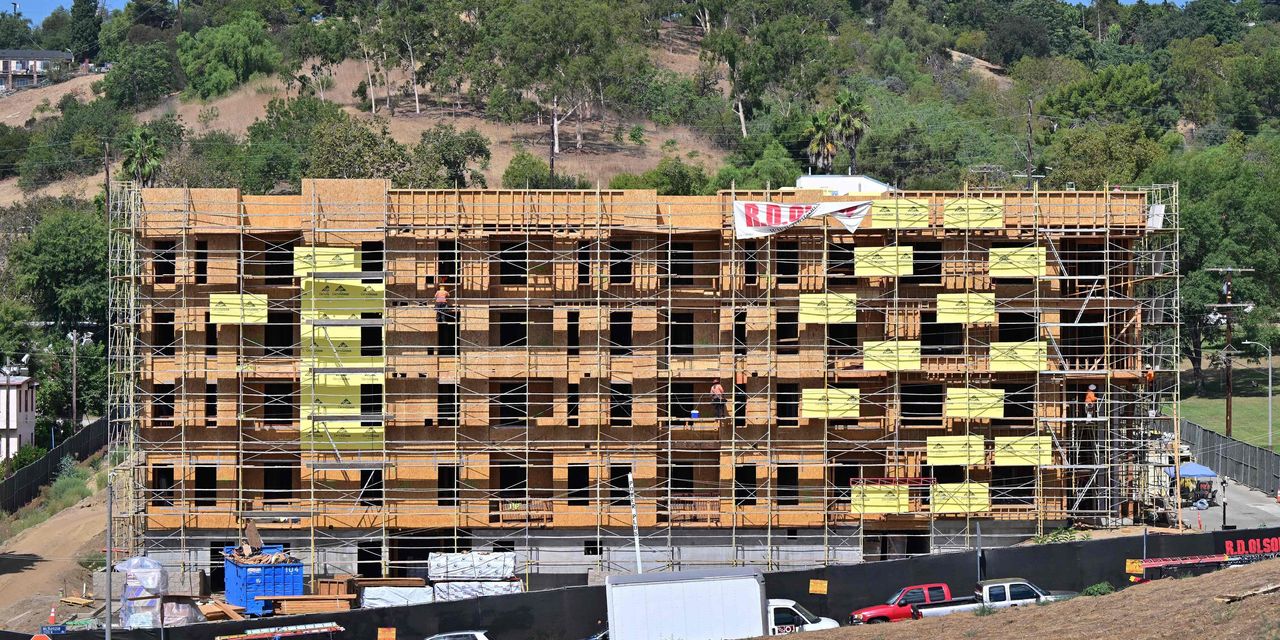

Housing experts blame the shortage of low-cost housing on two primary factors: the cost of land and the expense of borrowing money to build. High lumber prices and a scarcity of construction workers are problems, too, but land costs and financing are the biggies that the Biden Housing Supply Action Plan addresses.

It’s expensive to develop and build

When builders talk of land costs, they mean more than the price of vacant acreage. They also refer to costs imposed by local governments: impact fees, zoning rules that limit the size and spacing of new homes, and wasted time while projects are delayed by legal challenges and political opposition.

It’s often a long, costly slog to get approval for housing, especially for dwellings for low-income households, apartments and other multifamily units. As the Harvard Joint Center puts it in its 2023 report on the nation’s housing: “The national housing shortage is also the product of local restrictive zoning policies and other regulatory barriers that make it difficult to build a range of housing types at different price points.”

Cities overwhelmingly zone land for single-family houses, effectively banning duplexes and apartments. Minimum lot sizes mean builders can construct only so many houses on a block, so they build expensive homes to maximize profits.

“Considering everything, they are saying, ‘Well, only way to make the numbers work, we are focusing on this larger-size home,’” the NAR’s chief economist, Lawrence Yun, said in a C-SPAN interview in early August.

Related: ‘I lost bidding war after bidding war’: If interest rates are so high, why have house prices not declined?

Feds need to be firmer with local governments

Elected local leaders set the rules that drive up the cost of housing in communities blue and red. Several states, from California to Connecticut and Montana to Maine, have responded by restricting local governments’ land-use powers in order to promote multifamily and affordable housing.

Some housing advocates think the federal government should step in and compel local governments to make room for less expensive housing, such as apartments. In a March 2021 paper, Overcoming the Nation’s Daunting Housing Supply Shortage, Jim Parrott of the Urban Institute and Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics wrote that “federal policymakers should push communities to reorganize their approach to development from the ground up.”

The Biden administration adopted this approach. Its flagship program, Pathways to Removing Obstacles to Housing, dangles an $85 million pot of money. Local governments can receive grants from it to implement reforms that allow for denser housing, to plan transit-oriented development, to streamline permitting and to address gaps in financing, among other things.

It’s a well-meaning effort, with two problems: It lacks bite and it’s stingy. (The administration requested $10 billion and Congress appropriated $85 million.)

“It’s a nice idea, but, you know, we need some stick with the carrot,” says David Dworkin, president and CEO of the National Housing Conference. He means that the effort would be more effective if the federal government would withhold money from cities that refuse to relax zoning. Such an approach worked in the 1980s, when the feds threatened to deny highway funding to states that refused to raise the drinking age to 21. That was a shove, not a nudge — and it worked.

Playing hardball might yield results with housing, Dworkin says. “This is about having apartment buildings in communities, and duplexes or quadplexes, and the failure of communities to address the political pressure of residents who say, ‘I’ve got mine, no one else gets theirs,’” he says.

Listen: Best New Ideas in Money podcast: Solutions to help ease the housing shortage

A miserly response to an expensive problem

As for the amount of money that Congress approved: In their paper, Parrott and Zandi imagined a federal program that would hand out $50 billion per year for 10 years to cities that “ease regulations and other building restrictions.” The generous program would increase affordable housing by 275,000 units per year, they estimated.

If $50 billion per year for 10 years would help solve the affordable housing shortage, the $85 million Pathways to Removing Obstacles to Housing program is laughably small. It’s as if Parrott and Zandi presented a $500 repair estimate, and Congress fished three quarters and a dime out of its pocket. If $50 billion in funding would result in 275,000 affordable homes, as Parrott and Zandi estimate, then $85 million would be good for 468 affordable homes.

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) said it will ask Congress for more funding.

Other programs address the housing shortage indirectly. The Department of Transportation will chip in money to local governments that extend public transportation to and from affordable housing, partly through zoning reform. The Commerce Department, when handing out Economic Development Administration grants, will favor development projects that allow people to live closer to work.

Read: Lawmakers are banning single-family zoning. But are apartment buildings the ‘silver bullet’ for America’s housing shortage?

Making borrowing easier for developers

The other major way to stimulate the construction of affordable apartments is by making it easier and faster for builders to borrow money to fund their projects. HUD has come up with two solutions.

First, it has increased the threshold of what constitutes a “large loan” to build or rehabilitate apartments. The increase from $75 million to $120 million will reduce paperwork and costs to build or rehab large apartment complexes.

Second, HUD removed a $25 million cap on the size of FHA-insured loans on apartment construction that uses a streamlined Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). This means more apartment complexes will be eligible for the LIHTC, which reduces investors’ tax bills.

These tactics — loosening the purse strings to boost apartment building — might hasten construction for projects that have already won approval. But in the long term, this country can’t solve its housing shortage if cities and towns continue to use regulations to restrict new construction. If paying them to cut red tape doesn’t work, then state and local governments might have to withhold funding.

More From NerdWallet

Holden Lewis writes for NerdWallet. Email: [email protected]. Twitter: @HoldenL.

Read the full article here