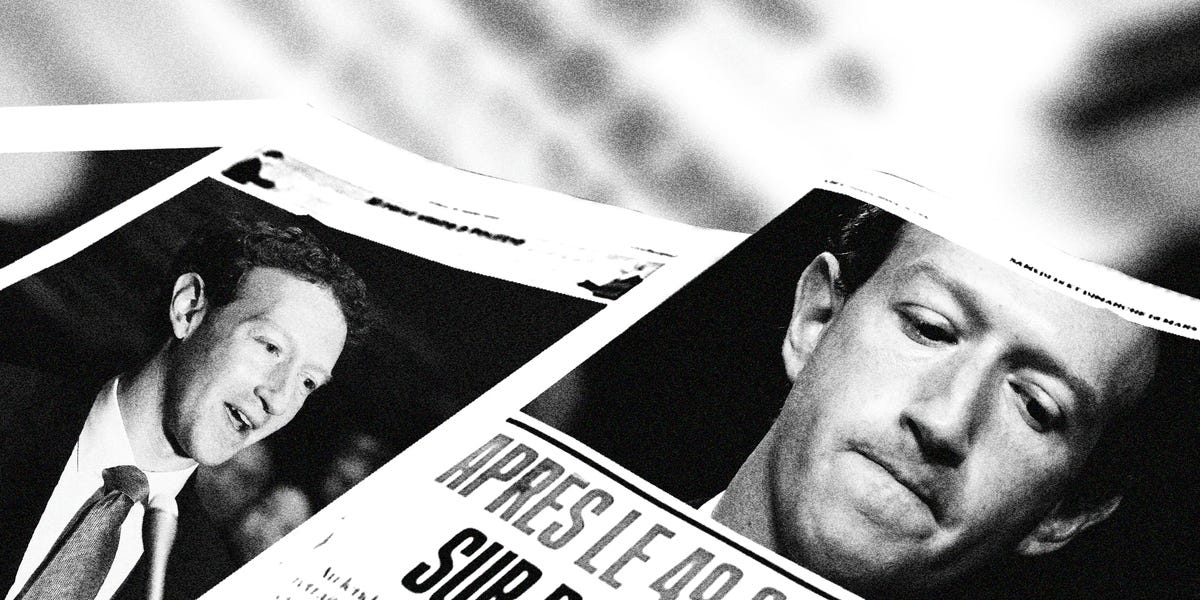

Mark Zuckerberg held regular discussions in 2017 and early 2018 about how to make news on Facebook more trustworthy and reliable. These talks started to coalesce around either buying a large, trusted news organization or Facebook starting its own.

At the time, Facebook, which had yet to rebrand as Meta, was still reeling from the politicization and related manipulation of the platform during the 2016 US presidential election, which contributed to Donald Trump becoming president. After initially dismissing Facebook’s role in politics and its influence on voters, Zuckerberg shifted his tone.

In a 2017 memo, he laid out how Facebook was dedicated to improving as a platform with responsibility to its users and to the news industry. “Giving people a voice is not enough without having people dedicated to uncovering new information and analyzing it,” Zuckerberg wrote. “There is more we must do to support the news industry to make sure this vital social function is sustainable.”

The tone was sincere, according to several people familiar with the note and Zuckerberg’s thinking at the time. He’d personally approved the Facebook Journalism Project, wherein a team at the company wrote checks to news organizations big and small.

But maybe there was a simpler way. “When it came to the fake news problem then, it was a question of, can we just do it ourselves?” a person with direct knowledge of the talks said.

Build it or buy it

Zuckerberg weighed his options: “Build it, or buy it?” another person familiar with the talks said. A top contender in the “buy it” category was the Associated Press, two people with knowledge of the process said. Zuckerberg was interested in Facebook effectively having its own wire service and AP fit the bill. Facebook’s mergers and acquisitions team became directly involved, but the idea lost steam as it became clear an outright acquisition of a major news publisher would draw regulatory scrutiny, one of the people familiar said. Zuckerberg also considered a permanent subsidy through his philanthropy the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. He ended up not liking that idea because using a charitable organization to “solve a Facebook problem” would probably look bad.

The “build it” talks revolved around Facebook creating its own news outlet, three people familiar with the talks said. That idea was also shelved, in part because there was concern about public blowback to such a launch.

Business Insider spoke to a dozen current and former Meta employees involved in high-level actions and decision-making around work with news and media publishers about the company’s increasingly tenuous relationship with the media. They were granted anonymity to speak freely without fear of retribution.

A Meta spokesperson, Tracy Clayton, declined to comment, referring BI to a company blog post from February announcing it was removing the dedicated news tab on Facebook.

‘Everything the news team built was killed’

Not long after these “build it or buy it” talks, Zuckerberg decided news media, on the whole, was much more trouble than it would ever be worth to him. In the past 18 months or so, Meta has moved away from any interest in the news industry or even tacit support of it. The company’s news budget had grown to $2 billion, including negotiated direct payments to publishers, two people familiar with the budget said. Last year, amid Meta’s “Year of Efficiency,” that budget was cut down to about $100 million.

“However important journalism is, it’s possibly the least interesting thing in the world to Mark now,” a former high-level Meta employee said.

That’s become clear. CrowdTangle, a tool that gave publishers performance insights, is shutting down in August. The Facebook Journalism Project is effectively dead. Nearly everyone on the news team within Meta was laid off or left between late 2022 and 2023. The Facebook platform started blocking news in Canada. Meta has entirely removed Facebook’s dedicated News tab in several countries, including the US, UK, and Australia, meaning news content is no longer intentionally surfaced, even if a user is looking for it (the tab used to be on the Facebook homepage).

Executives like Adam Mosseri, the head of Instagram and Threads, said explicitly such platforms are now decisively showing people less news and related political content. The entire algorithm of Facebook and Instagram, most notably, was also transitioned to one that recommends “unconnected content,” or content based on what a user has engaged with. As no news content is made readily accessible on Meta’s platforms, there is effectively no way a user can randomly interact with it and be shown more.

“Everything the news team built was killed. It was a full turnaround from massive budgets to fund news to everything being essentially turned off one day,” the same former high-level employee said. “Internally, there was no drama about it, Mark is not emotional like that. It was, ‘This is clearly not helping our business, and this is a business decision. We’re done.'”

An early sign that Meta wanted to distance itself from the news industry came in 2022 when the company changed the name of one of its first and most successful products, the News Feed (a separate product from the News tab), to just Feed.

Australia

Zuckerberg decided Facebook’s relationship with the news industry had become untenable toward the end of 2019. That was when Australian government officials first informed Facebook and Google that the country was pursuing a new law, the News Media Bargaining Code. It would require both companies to negotiate payment deals with news publishers to continue hosting links to their content.

Within Facebook, dealing with the news media immediately went from a peripheral annoyance, an occasional frustration that had no real effect on Facebook’s business, to a potentially massive cost.

“Australia alone was now going to cost us about $100 million a year,” a person who worked for Meta at the time with knowledge of the situation said. “Assuming other countries would follow suit, which they did, the cost quickly went up to several billion a year. And it was then that the top executives were like ‘Time out, what the fuck are you all doing in news that this is suddenly a multibillion-dollar risk?'”

The NMBC became law in 2021, and every Meta insider BI spoke to for this story argued it was orchestrated by political juggernaut Rupert Murdoch, the founder of the News Corp. empire. News Corp. was the first to strike a deal with Facebook on payment for news content in Australia after the law was passed. A representative of News Corp., James Kennedy, declined to comment but emailed BI copied sections from several news reports about the NMBC that mentioned News Corp. was not the sole beneficiary of the law. He also highlighted mentions of Rod Sims, the former chair of Australia’s competition authority, and characterized him as the architect of the NMBC.

In mid-2017, Zuckerberg and a handful of other top Facebook executives did a management off-site with Murdoch and his top executives from News Corp. and Fox, including his son Lachlan, a person who attended said. The group spent a day together, dining and talking business tactics. Murdoch and Zuckerberg’s yearslong relationship, while never outright friendly, turned “tense, very tense,” when Australia passed the NMBC, a person who worked with Zuckerberg said. He was involved directly in negotiations with Australian officials like Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg in the run-up to its passage.

During a 2 a.m. call with Joel Kaplan, Meta’s vice president of policy, and Campbell Brown, who was vice president of news partnerships until leaving last year, and a small number of other Facebook executives, Zuckerberg decided that Facebook would simply turn off news in Australia for good. “We did all the calculations on what would happen if we removed and blocked all the news there, and it was a tiny, almost negligible impact on engagement,” one of the people familiar with the situation said.

Two weeks later, Zuckerberg reversed course when his talks with Frydenberg resulted in some amendments to the law, effectively removing the threat of arbitration if publishers weren’t satisfied with Facebook’s deals.

Since the law passed, Meta has paid around $100 million a year for news content in the country, according to two people familiar with the deals that the company has entered into with Australian publishers. “It did nothing to decrease tensions with the media there or increase goodwill in any way,” one of the people said.

No turning back

Meta’s bill to Australian publishers is expected to be much lower this year, as the company said recently news consumption on Facebook in Australia is already down 80% compared to last year.

Meta removed the News tab in Australia and said in April that “we will not enter into new commercial deals for traditional news content in these countries and will not offer new Facebook products specifically for news publishers in the future.” Any deals Meta has with publishers in the US and UK, including those with News Corp., have already expired. Remaining deals in Australia, France, and Germany are set to do so in the next few years.

When Canada passed a law similar to Australia’s last year, Meta simply and decisively turned off news content on Facebook and Instagram. It was not a tortured decision. If news organizations attempt to squeeze money out of Meta in the future, the company’s plan is to turn it off entirely.

“If the whole Australia thing had not happened, maybe Facebook would never have gotten out of news at all,” a former Meta employee with knowledge of the situation at the time said. Now, “there is no going back.”

By and large, media executives blame Meta and Google for gobbling up most of the available digital-advertising dollars, leaving news organizations to fight for scraps. The news industry has been in a 20-year struggle to figure out a modern business model and it continues to shrink significantly. Meta is more successful than ever. But its relationship with media remains fraught.

After Trump’s election and the acknowledgment of misinformation on Facebook, which Zuckerberg said would be fixed, the next three years saw the Cambridge Analytica scandal, genocide in Myanmar, user-privacy issues, a whistleblower, and the January 6, 2021, Capitol riots. Those are just a few instances of Facebook being blamed directly or at least criticized for its role in political and public upheaval.

“You’d go into a meeting with a TV network or a news company and they would just tell us what assholes we are for an hour,” a person who worked for years in such a role at Meta said. Even when Facebook started writing more checks to more news organizations as part of its News Accelerator Program — which started in 2018 with a budget of $300 million to hand out to publishers, and later with direct multimillion-dollar deals with publishers for their content — relations did not improve.

“People in news feel like Facebook owes them something,” one of the former high-level employees said. “But eventually, if you push Mark to the brink, his response is ‘Nope, I’m done.'”

There were mixed views among executives who worked closest with Zuckerberg on supporting news. Zuckerberg was initially fine directly engaging with the media on their terms, if only because “he found it an interesting problem to solve, like ‘here’s an important industry with no business model, maybe I can fix it,'” one of the high-level former employees said. When he switched sides, so did everyone else.

Are you a Meta employee or someone with a tip or insight to share? Contact Kali Hays at [email protected] or on secure messaging app Signal at 949-280-0267. Reach out using a non-work device.

Read the full article here