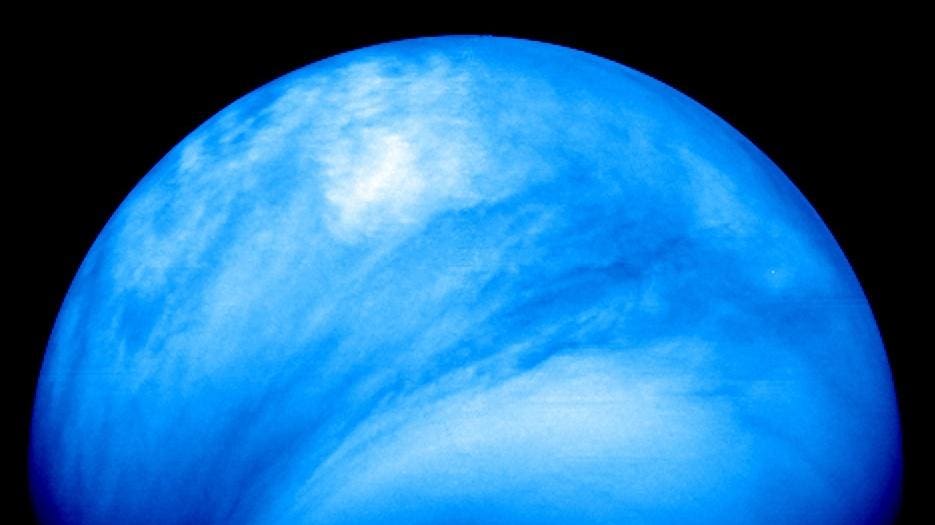

More traces of a gas thought to be a sign of life have been found in the clouds and haze layers of Venus.

First reported in 2020, the initially controversial detections of molecules of phosphine (PH3) was today confirmed with news of extensive additional detections presented at the National Astronomy Meeting 2023 at Cardiff University in Wales, UK.

They come primarily from the first 50 of 200 hours of observations using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii—far more than the eight hours used for the original detection—but also involve new data from NASA’s now defunct Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) airplane.

Unexplained Chemistry

Phosphine, which comprises hydrogen and phosphorus, is a flammable and toxic gas on Earth that’s often thought of as swamp gas. It’s only produced by microorganisms living in a very low oxygen environment. Its apparent presence at Venus indicates that conditions for bacteria exist there or, at the very least, unexplained chemistry.

Although the surface of Venus is hot enough to melt metal, its high clouds are about 86ºF/30ºC. However, they consist of 90% sulphuric acid, which would put any microbes that did exist there in the “extremophile” category. Any microbial life would have to be both airborne and acid-resistant. So these detections of phosphine are evidence not of life, but that we simply don’t understand the phosphorous cycle on Venus.

New Detections

JCMT’s latest detections of phosphine from February 2022 and May 2023 are significant because they hugely extend the scope of the initial study. They also suggest that there’s a steady source of phosphine either in or below the clouds of Venus.

“We now have five detections over the last few years, from three different sets of instruments, and from many methods of processing the data,” said Professor Jane Greaves, an astrobiologist at the School of Physics and Astronomy at Cardiff University whose team has been conducting tests as part of a 200-hour legacy survey using JCMT. “We’re getting a clue here that there is some steady source, which is the point of legacy surveys—to show whether that’s true or not,” said Greaves.

In November 2021 scientists using SOFIA found no traces of phosphine, but Greaves’ team’s reprocessing of the data revealed phosphine in the planet’s upper clouds. “I did one tiny tweak to the way they looked at the data and you can certainly get something out,” said Greaves. “I didn’t do anything elaborate—just standard techniques.”

Phospine Has ‘Wings’

One of the most remarkable aspects of the continued detections is that Greaves and her team could see “wings” in the data. “We’ve got these absorption lines in the atmosphere that spread over a big range of wavelengths—we’re seeing in effect molecules moving about really fast,” said Greaves. “We’re looking at the tops of the clouds, or middle of the clouds even, and this is the first time we’ve been able to do this.”

Greaves also revealed that there may be traces of phosphine in archive data from NASA’s Pioneer Venus 1 collected in 1978.

Future Missions to Venus

No mission has visited the Venusian atmosphere since 1985. However, there’s now a push to re-discover and properly explore the planet that comes closest to Earth.

Greaves said that to study Venus in infrared is a real priority in the search for phosphine and other biomarker gases, such as ammonia. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has that capability, but it’s so sensitive that it cannot look at any object close to the sun—like Venus.

Luckily, there are three missions to Venus planned for the coming years—two orbiters and one lander. Both scheduled to arrive at Venus in the 2030s, NASA’s VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy) will map Venus’ surface from orbit to determine the planet’s geologic history while ESA’s EnVision will measure the planet’s subsurface features for the first time. EnVision will also monitor trace gases in the atmosphere.

Finding Phosphine In-Situ

However, it’s DAVINCI+ (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging Plus) that could provide a phosphine detection in-situ. Scheduled to arrive in 2031, during a fatal 63-minute descent it will sample the Venusian atmosphere half a dozen times and fire lasers through it and measure the gases.

“They have four of these laser wavelengths to allocate and only three are decided,” said Greaves. “We made our case for phosphine and we’re just waiting for hear back.”

Observations are continuing at JCMT, with the remaining 150 hours of observations scheduled to be used-up this year while Venus is well positioned. “Venus is approaching the Earth at the moment,” said Greaves, who added that when the planet is big and bright it makes observations much easier. “So we start tonight in Hawaii and tomorrow we get the data. It’s very exciting.”

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.

Read the full article here