The bill asks fiduciaries to focus only on “pecuniary” factors. On the one hand, this is redundant as the DOL rule does not force fiduciaries to consider ESG. On the other hand, what is not “pecuniary”? Extreme weather events that affect cash flows? DEI that affects corporate culture? Human rights scandal that almost brought Nike down?

Congressional Republicans have introduced several new bills last week to circumscribe the role of ESG in investing. In some of the articles to follow, I intend to look at these bills in greater detail. Let us start with the so-called ESG Act or “Ensuring Sound Guidance Act” introduced by Reps. Andy Barr (R-KY) and Rick Allen (R-GA). The bill was introduced in the 117th Congress on March 18, 2022 and has been reintroduced now in the 118th Congress.

This legislation would require investment advisers and ERISA retirement plan sponsors to prioritize financial returns over non-pecuniary factors when making investment decisions on behalf of their clients. The press release issued on the re-introduction of the bill states that the intent is to “protect retail investors’ retirement and investment accounts from asset managers who put environmental and social goals ahead of returns.”

Rep Barr’s statement

“Asset managers should be in the business of maximizing returns for investors, not pushing their own political agenda at the expense of everyday Americans. Our proposed legislation safeguards the savings efforts of hardworking Americans. This critical legislation not only guarantees that advisers make prudent investment choices based on financial factors, but also empowers savers to decide how their money is invested, contrary to the Department of Labor’s (DOL) finalized rule,” said Rep. Barr. “We must take significant action to protect retail investors and retirees from the cancer within our capital markets that is ESG, which prioritizes higher-fee, less diversified and lower return investments.”

Endorsed by several institutions:

The ESG Act has been endorsed by ex-SEC chairman, Jay Clayton, and a long list of institutions including the American Petroleum Institute (API), Heritage Foundation, FreedomWorks, Club for Growth, Americans for Prosperity, Americans for Tax Reform (ATR), American Free Enterprise Chamber of Commerce, Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), Advancing American Freedom, National Mining Association (NMA), National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF), Texas Public Policy Foundation, and auditors, comptrollers and treasurers of several states such as Kentucky, West Virginia, Louisiana, North Dakota, South Carolina, Indiana, Oklahoma, Idaho, Texas, North Carolina, Arkansas and Ohio.

What is a pecuniary factor?

Let us take a closer look at the actual language of the bill.

“a fiduciary of a plan shall be considered to act solely in the interest of the participants and beneficiaries of the plan with respect to a plan investment or investment course of action only if the fiduciary’s action with respect to such investment is based only on pecuniary factors. The fiduciary may not subordinate the interests of the participants and beneficiaries in their retirement income or financial benefits under the plan to other objectives and may not sacrifice investment return or take on additional investment risk to promote non-pecuniary benefits or goals. The weight given to any pecuniary factor by a fiduciary should appropriately reflect a prudent assessment of the impact of such factor on risk-return.”

“Pecuniary factor” is defined as “factor that a fiduciary prudently determines is expected to have a material effect on the risk and return of an investment based on appropriate investment horizons consistent with the plan’s investment objectives and the funding policy established pursuant to section 402(b)(1).”

I have a few comments on this definition.

Redundant?

First, this seems redundant to the DOL’s position, as summarized by Latham and Watkins, that “a fiduciary may exercise discretion when determining what factors are relevant to the risk-return analysis and the fiduciary remains free to determine that an ESG-focused investment is not in fact prudent.” Consider cases where extreme weather causes cash flow shocks to say agricultural firms on account of higher cost of growing crops or a theme park operator suffers poor attendance, or a cruise ship business must cancel cruises. Surely, the recurrence of these factors needs to be considered by the fiduciary, failing which they would be derelict in performing their duties. And these considerations would surely be “pecuniary” in nature.

ESG is pecuniary

Second, some of us view ESG as purely an attempt to encourage production and disclosure of signals that affect the firm’s future cash flows and/or risk associated with the firm that are not adequately captured by the current disclosure system. Surely, understanding the nature of the workforce, the costs incurred on that account, spikes in abnormal labor turnover, the extent of reliance on contractors and the compensation paid to such contractors can be seen as both “S” and “pecuniary.”

Index funds should consider ESG because of horizon issues:

Third, one of the major problems with index funds is that they don’t address the time horizon of the beneficiary. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the median age of an American worker is 42 years. Such a worker-investor will retire in 20-25 years or somewhere in the 2040-2050 decade. Shouldn’t the asset manager factor in a reasonable probability that the social costs externalized by firms might have to be internalized at some point before 2040, either by the company or the portfolio of companies as a whole, in the future via customer defection, difficulty in hiring talent or simply regulation? Isn’t this one of the key motivations behind considering ESG factors in investing? How does an ESG ban square with the bill’s objectives to enable fiduciaries to make “prudent investment choices”?

But what really is or is not “pecuniary”?

Third, I struggle with the word, “pecuniary.” What is “not” pecuniary in the world of investing? If a fiduciary believes that DEI positively or negatively affects corporate culture, which, in turn, has been shown to affect innovation, productivity and compliance activities of the firm, is DEI not pecuniary? Is investing in a “bitcoin” fund not pecuniary given that there is no convincing model that I am aware of that can link fundamentals of bitcoin to its valuation.

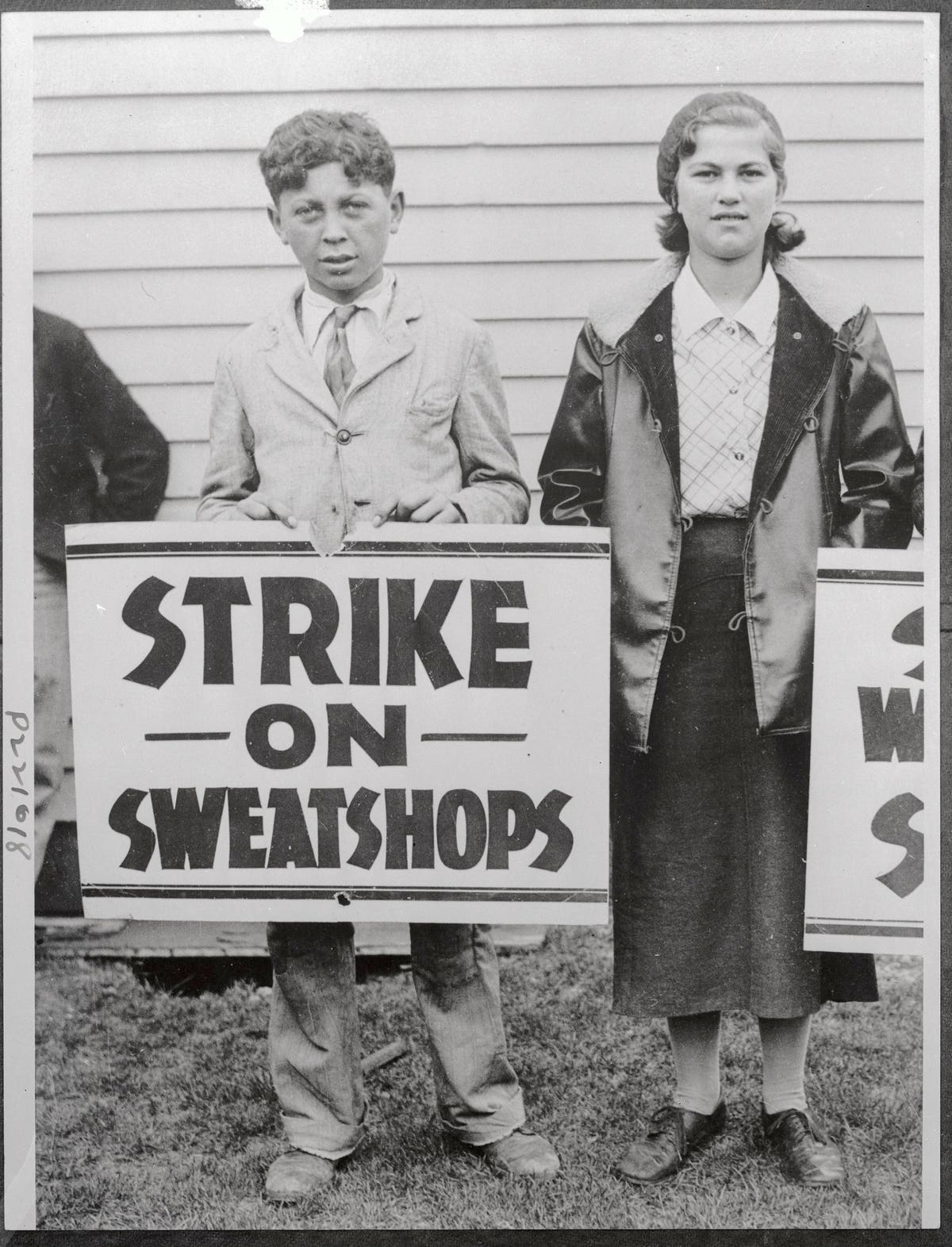

For an even more extreme example, is consideration of human rights not pecuniary? When word got out that Nike was relying on child labor in Cambodia and Pakistan, many of Nike’s customers stopped buying Nike’s products. The scandal arguably threatened the very existence of Nike as a going concern. A good fiduciary would have identified this risk and potentially sold Nike to avoid the large stock price hits that ensued once the scandal come to light. The U.S. Department of Commerce has sanctioned 11 Chinese companies that it claims are using “forced labor involving Uyghurs and other Muslim minority groups.” Surely, this was a “pecuniary” factor that a fiduciary would have done well to identify in advance and divest from these stocks.

And, what about the vast array of so-called “pecuniary” funds including value funds, growth funds, quality funds and the like. All these are based on investor expectations that link some model in the fiduciary’s head to future returns or cash flows or risk of their investments. Most of these expectations rarely work out in practice after the fact as some style of investing outperforms others, depending on a myriad of factors. If these are “pecuniary” in nature, why is a theory linking ESG factors—such as extreme weather events or corporate culture or human capital or plain old governance—to expected future cash flows or risk, not considered “pecuniary”? It would be ludicrous for Congress to prevent investors from choosing value funds, emerging market growth funds, sector-specific funds and the like. How is an ESG fund any different?

Limits on Secretary of Labor’s power

Four, one of the provisions of the Barr bill states, “the Secretary of Labor may not finalize, implement, administer, or enforce the proposed rule entitled “Prudence and Loyalty in Selecting Plan Investments and Exercising Shareholder Rights” (86 Fed. Reg. 57272) and dated October 14, 2021.”

I don’t see what is objectionable in the DOL rule, as it stands. The Biden DOL rule, in my view, is a clear “return to neutrality.” As Latham and Watkins state, the Final DOL Rule amends the Prior Rule to delete the pecuniary/non-pecuniary terminology and to soften the prudence test to require that a fiduciary’s determination be based on factors that the fiduciary “reasonably determines” are “relevant” to a risk-return analysis, rather than factors that the fiduciary “prudently” determines are expected to have a “material effect” on the risk-return analysis.

“Weight on pecuniary factor should reflect contribution to risk-return:”

Finally, consider the language: “the weight given to any pecuniary factor by a fiduciary should appropriately reflect a prudent assessment of the impact of such factor on risk-return.” This is an odd statement and difficult to implement in practice. Consider an array of investing styles out there: (i) dividend based; (ii) growth investing; (iii) value investing; (iv) so-called loosely defined quality investing; or (v) momentum investing.

We do have a lot of archival data on how these styles have worked in the past in terms of their contribution to risk and returns of the portfolios. However, one of the oldest adages in investing is that history need not predict the future. How is a fiduciary supposed to appropriately reflect a prudent assessment of each of these so-called pecuniary factors on risk and return of retirement portfolios? Overweight growth and momentum because these have done well in the last decade? What if these factors fail to do well in the future? Or do the drafters of the bill mean something else?

So, what is the bottom line?

“ESG” can be easily justified as a “pecuniary” factor depending on the specific context and investments being considered. A blanket rule, either to explicitly consider or explicitly ignore, ESG factors is ill-advised and counterproductive. In fact, the stated intention of the bill to enable fiduciaries to make “prudent investment choices” might be best achieved by letting them decide for themselves what factor is or is not relevant to their specific portfolio.

Read the full article here