I’ve got good news, and I’ve got bad news. Let’s get the bad news out of the way first. (And if you just don’t need it, skip down two paragraphs.) Increasing numbers of teachers have left education, citing burnout and a lack of support. At least 300,000 public-school teachers and other staff left the field between February 2020 and May 2022, and, for the past decade, fewer people have chosen to teach. Despite how important teachers of color are to the success of all students and especially students of color, the U.S. teaching force is still only 20% non-white, and reports indicate that teachers of color are leaving at higher rates than their white counterparts.

Unwilling or unable to get at the root causes of the teacher shortage, states are calling on the National Guard, veterans, custodians and bus drivers to teach. Some states, including Arizona and Florida, announced they are lowering or eliminating job requirements for teachers entirely. Staffing shortages are greatest in high-stakes subjects like science, math, and special education.

But earlier this year, without much fanfare, a report by the U.S. Department of Education uncovered that the number of people enrolled in teacher preparation programs actually rose 6% from 2019 to 2021. (Thank you to Chad Aldeman and The74 for being the first to break it.) Teacher preparation enrollment is up in 37 states and the District of Columbia since 2019. To be clear, even with this growth, enrollment isn’t nearly back to where it was a decade ago, but the trend-line is real, and it’s positive for the first time in a long time.

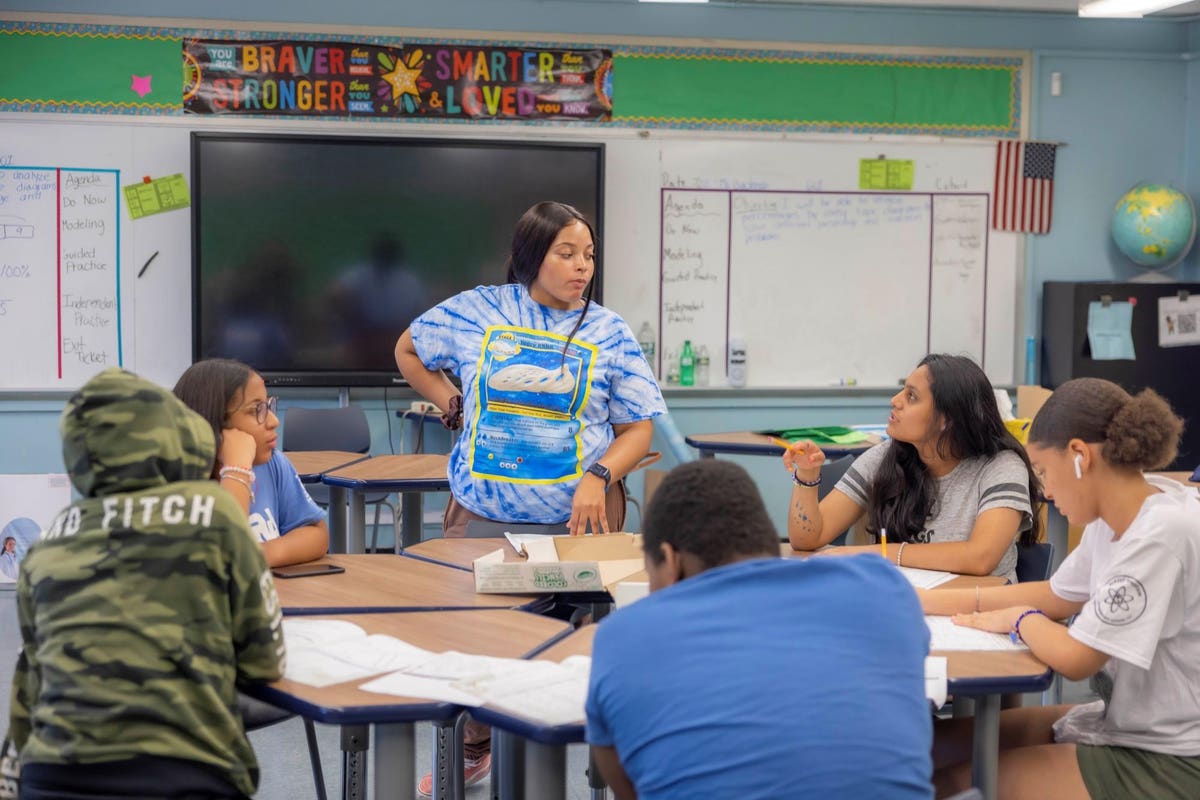

Kathlene Campbell, president of the National Center for Teacher Residencies, which supported 11 more residencies in 9 more states in 2022-23 than they did three years prior, attributes this uptick to a spirit among young people. This younger generation of teachers is “driven by impacting social change and trying to uplift their communities,” an insight echoed by others I spoke to and that’s showing up broader trends around the Great Resignation. Breakthrough Collaborative gives high-school and college students a pathway to teaching through mentoring and tutoring younger students and has also experienced enrollment growth. Vince Marigna, National CEO, said he’s seeing “young people want to make a difference in their communities, advance social and racial justice; they see the education field as a critical place to shift systems and conditions” and are “giving their younger selves what they wish they had.” Shannon Richardson, a high school science teacher in Brooklyn, NY, said she thinks what draws most people to the STEM fields is “curiosity, desire to create, and a desire to solve the world’s problems.” Her desire to teach was fueled by a “desire to share that joy.”

Despite the overall increases, challenges persist. If the well-worn truth that “as goes California goes the nation” holds true, we have reason for concern. The California State University system prepares 4% of all teachers nationally, and it’s seen declining numbers since 2017, said Fred Uly, Director of Educator Preparation at CSU, Office of the Chancellor. In the midwest, 25% of regional or local universities are predicted to close. How many of those potential closures also have educational programs? A report by NCTQ showed that, while enrollment is up across types of preparation programs, growth in traditional universities, where the vast majority of teachers are still prepared, lagged growth in non-traditional programs, something my organization, Beyond100K, predicted at the end of 2022 in our Trends Report.

The UTeach Program out of UT Austin supports 55 universities in 23 states and the District of Columbia. Katey Arrington, their associate director, said that half those programs are growing or holding steady and half shrinking. The differentiator: The ones that are growing are redesigning their programs, pathways, supports, and incentives.

One way programs are doing that is by reallocating or reducing cost. As Campbell explained, residencies shift the cost from the teacher candidate to the district or university, making becoming a teacher more affordable. Given that teachers continue to under-earn others with equivalent years of education, affordability is key.

Another is messaging. Arrington said she’s seen programs benefit when their recruiting messages highlight STEM as an equity issue “the difference each teacher will make in students’ lives, particularly for those who are now not being served or not being served well in the system.”

But recruitment is only half the puzzle. It turns out that more than enough people are entering teacher preparation programs to fill vacant seats, but the pipeline is leaking, with low completion rates in teacher certification, particularly for candidates of color. Juliette Guarino Berg (@JulietteScience), an elementary science teacher in New York City, reflected on a friend who switched out of science in college. “Would her classmate have changed her mind if she had felt more supported?”, she asked. She became a science educator so that every child in her classroom could feel supported and capable of success.

An affordable and creative tool for strengthening the teacher pipeline is providing small emergency funds to help teacher candidates finish their degrees when life things come up unexpectedly. The Last Mile Education Fund has used this to great effect for undergraduate STEM majors. Arrington noted a trend among programs that are growing: “they are innovating by offering more and different supports to students.”

She posed a provocative question — researchers, pay attention. Is it possible that the growth in alternative certification is being driven by uncertified teachers who have been thrust into classrooms scrambling to get certified? Digging into the data will be critical, as will creativity and innovation at every stage of the teacher preparation pipeline, if we’re to turn a decade-long decline into the uptick in new teachers our students need.

Read the full article here