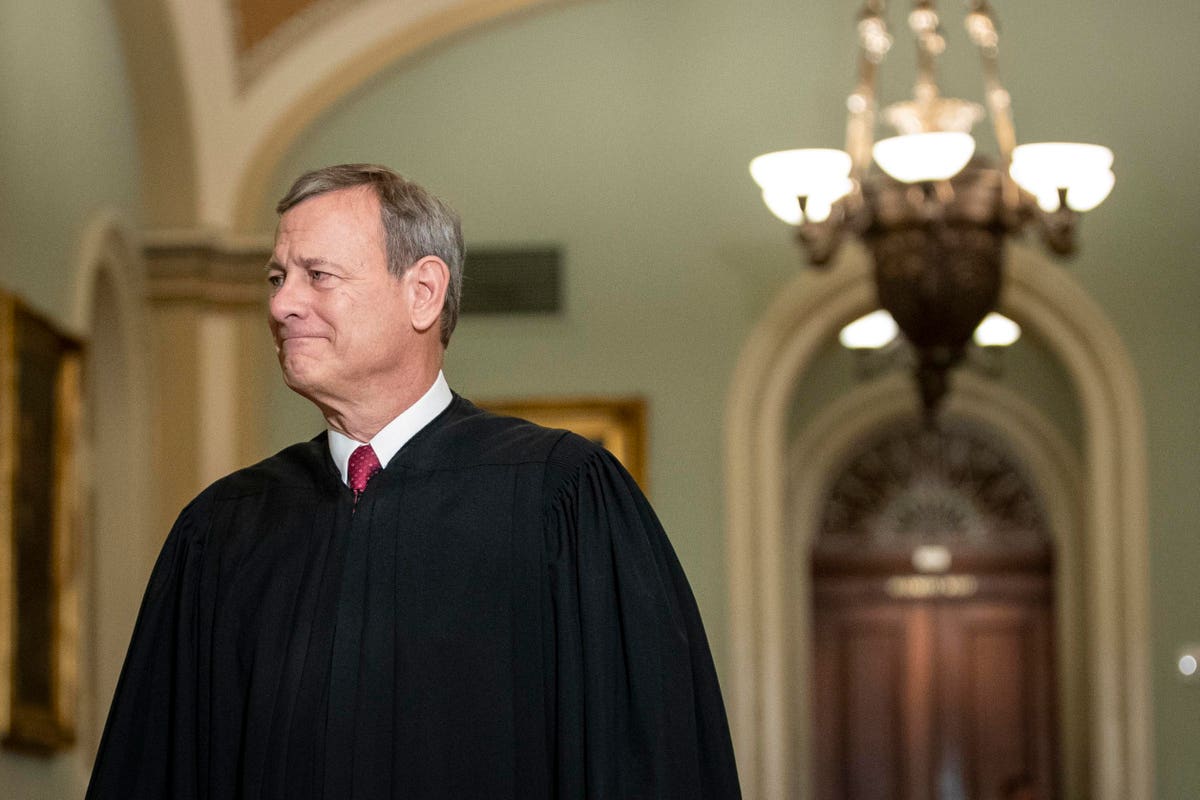

The Supreme Court recently struck down the use of affirmative action in college admissions, with Chief Justice John Roberts’ majority opinion stating the “..lack [of] sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race, unavoidably employ race in a negative manner, involve racial stereotyping, and lack meaningful endpoints.” The minority strongly disagreed. Justice Elena Kagan worried about “a precipitous decline in minority admissions.” Elite universities, she added, are “the pipelines to leadership in our society.”

“Colleges need to be ready to openly reaffirm their commitment to educating students of all backgrounds and they must put into place the programs that will produce results,” Jerome Lucido, Director of the USC Center for Enrollment Research, told me. “They must also resist the chilling effects of a court decision.”

The institutions most likely to be dramatically affected by the latest ruling are the 200 colleges and universities generally regarded as “selective,”meaning they admit 50% or fewer of their applicants. Regarding the latest Supreme Court ruling, Jon Boeckenstedt, Vice Provost for Enrollment Management at Oregon State University, commented to me, “This will have minimal effect on the vast majority of colleges and universities whose enrollment is not selected from large numbers of highly qualified candidates, but rather based on who decides to apply in the first place.”

Kevin Welner, Director of the National Educational Policy Center, comments in the Washington Post that “affirmative action programs have been, for a half-century, a way for elite colleges and universities to place flimsy band-aids on massive societal inequalities.”

While this decision has a major impact on a large number of students of color, it does nothing to address the greatest barrier to educational attainment for under-represented students, college costs, which have increased, unabated. While the college admissions community can be lauded for its role in increasing opportunity and access, it has failed miserably at improving what has a more significant impact on the majority of students: affordability.

An analysis of College Board data by My eLearning World, found that the average price of going to a private college went from $2,930 per year in 1971 to $51,690 annually in 2021. That is an increase of roughly 4.6 times the inflation rate. The price tag for public college has surged, too, going from $1,410 annually in the early 1970s to $22,690 for in-state students and $39,510 for out-of-state students. Per the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, State funding for public two- and four-year colleges in 2018 was $6.6 billion less than in 2008, after adjusting for inflation. The net cost of attendance for even the most economically disadvantaged (Pell Grant recipients), according to the Urban Institute, has doubled over the past 30 years to almost $15,000.

This is perhaps the most significant criticism of the present system: Its economic costs fall most heavily on those who can least afford them. A study by the Student Borrower Protection Center found that four years after graduating, Black students hold almost twice as much student debt as their white peers. Ninety percent of Black students take out student loans to pay for college (compared to 66% of white students) and have a median student loan balance of over $30,000.

We have developed a system that impoverishes many of our most vulnerable citizens with a lifetime of debt: 43 million people in the U.S. have student loan debt, with an average family debt of more than $58,000 according to Nerd Wallet’s 2022 Household Debt Survey. Thanks to a 1979 revision of section 439A of the Higher Education Act of 1965, student loan debt can no longer be discharged in bankruptcy. This system needs to be changed.

Senator Bernie Sanders’ proposals, guaranteeing tuition-free community college and loan-free four-year colleges for low-income students from single-parent-households and doubling the Pell Grant (now maxing out at $6,495, in 2024), would have a major impact. So would expanding funding at the high school and post-high school levels for certificate and licensure programs in the trades or the medical fields.

One study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found “the fraction of students from low-income families did not change substantially between 2000 and 2011 at elite private colleges, but fell sharply at colleges with the highest rates of bottom-to-top-quintile mobility.”

Affirmative action for the wealthy, including legacy admissions; recruiting in sports such as crew, fencing, and golf; and admissions preference for donors, children of faculty and staff, and “dean’s admits” should be curtailed or eliminated.

Colleges and the government are taking steps in this direction. MIT, Wesleyan, Johns Hopkins, CalTech and others no longer take legacy status into account in admissions decisions. Some prestigious law schools and medical schools are pulling out of the U.S. News & World Report rankings. Columbia University recently pulled out of the college undergraduate rankings, joining the Rhode Island School of Design, Colorado College, Bard College, and Stillman College.

New FAFSA rules that allow for families to know their Pell eligibility prior to filling out the FAFSA are helpful. A positive proposal in both the Democratic and Republican bills covering college costs would offer earlier forgiveness for borrowers with low balances, who make up the majority of those defaulting on their loans, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Bolder action will be needed, such as allowing student debt to be discharged in bankruptcy, providing sufficient state and federal funding and controlling costs for lower and middle income students to able to attend college without accruing unsustainable debt.

Read the full article here