Six months after China lifted Covid-19 restrictions and reopened its borders, visitors are staying away in droves.

The Wall Street Journal reported last week that Shanghai’s and Beijing’s airports are nearly deserted. In the first half of 2023 less than a quarter of visitors travelled there compared to 2019.

The problem has little to do with recovery from the Pandemic. Instead, it’s the steady rise in geopolitical tensions; China’s mounting economic and social problems, and the “decoupling” of China from the West.

Foreign direct investment has plummeted by 80 percent year over year. Thus, businesspeople have less reason to travel there. And more reasons to stay away. Employees at several US consulting companies have been detained, their offices searched. The business climate is no longer roll out the red carpet for foreign businesspeople. Pandemic supply chain snafus have made reliance on China a bigger risk than was realized.

Fewer deals mean fewer relationships and fewer reasons to travel there.

Remembering When China Was the “In” Country

Excitement was in the air during my first trip to China, in 2002. Globalization was on the rise, and the world was flat, according to influential columnist Tom Friedman. My book, “Driving Growth Through Innovation” had just been translated into Chinese. Citibank, IBM and other multinationals invited me to address their top leaders across Asia. This was at a time when China was considered a juggernaut, and the “China Price” was wiping out America’s small and mid-sized manufacturers by the score. Even the sleepiest American manufacturers were encouraged to go to China to find low-cost contract manufacturers to take over production. And everybody wanted to go there to check out this economic miracle that was lifting millions out of poverty.

When China Began to Change

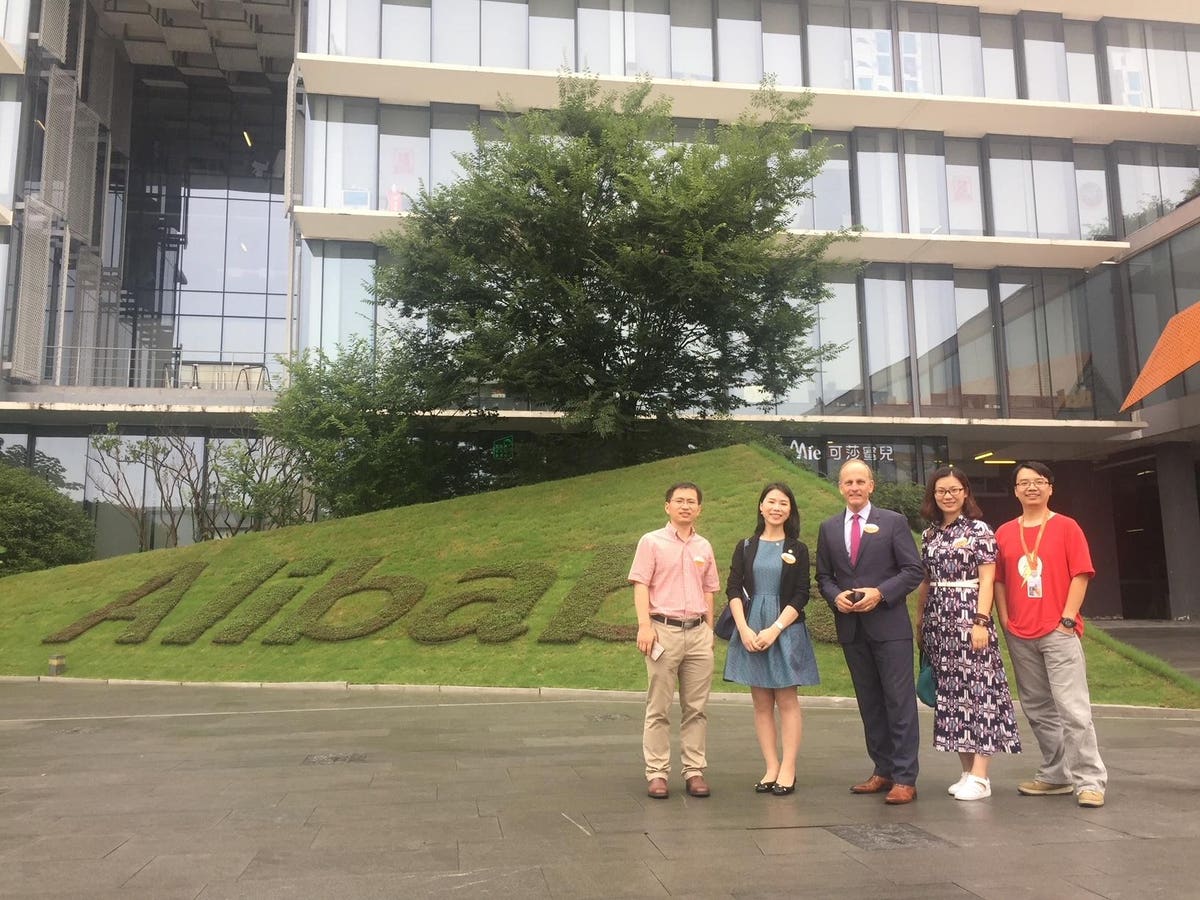

Fast forward to my most recent trip to China, in 2016, and China was beginning to change. In June of that year, I traveled to Beijing for a three-city lecture tour arranged by business school professor of innovation and strategy Chen Jin, of Tsinghua University’s School of Economics and Management in Beijing. As always, I enjoyed the interaction with super sharp businesspeople, and with his bright and eager graduate students, many of whom spoke almost perfect English. Professor Chen was kind enough to set up interviews with executives at Tencent, Alibaba and Xiaomi, a fast-growing mobile phone and internet company, and I was amazed at the amount of product, service and business model innovation in China.

A visit to Alibaba on a Sunday morning revealed an organization bustling with young people willing to work even on weekends, and to live in block after block of dorms adjacent to office buildings. The Chinese English-language dailies reported on a seemingly endless array of measures designed to fuel the nation’s future. Announcements that China was building the world’s most powerful supercomputer; service robots to help serve China’s aging population; the launch of yet another Chinese rocket called The Long March. And most importantly Belt & Road Initiative, the trillion-dollar Eastern Europe and Asia infrastructure project, and China’s future seemed bright, unstoppable.

Yet even then, as I look back, there were storm clouds on the horizon. In a report I wrote upon return from China (“Five Windows on Where China is Headed Next”) I listed a growing host of issues: among them China’s price advantage for manufacturing was disappearing. In 2002, China’s labor costs were just 60 cents an hour, but by 2016 they’d risen to $14.60 an hour, compared to $22.68 in the US. Also of concern: the slowdown in China’s GDP growth (from 10 percent to 6 percent), a ballooning debt burden, polluted ground water and toxic air, it’s Ghost Cities, and stock market 30 percent plunge. In the report, I quoted Morgan Stanley’s chief global strategist warning that “China is a threat to the United States not because it is strong, but because it is fragile.”

Nostalgia for the Early Days of China’s Rise

Fragile or simply transitioning from one business model to the next, the China that is emerging is dramatically different from the China of the recent past. Isolation and distrust grow, as relationships diminish.

“Fewer tourists and businesspeople mean fewer opportunities for foreigners to see China with their own eyes and interact with locals, notes Wall Street Journal reporter Wenxin Fan. “This is an important factor in reducing geopolitical tensions.”

One journalist who has gone to China recently is Tom Friedman of the New York Times. “I just returned from visiting China for the first time since Covid struck. Being back in Beijing was a reminder of my first rule of journalism: If you don’t go, you don’t know. Relations between our two countries have soured so badly, so quickly, and have so reduced our points of contact — very few American reporters are left in China, and our leaders are barely talking — that we’re now like two giant gorillas looking at each other through a pinhole. Nothing good will come from this.”

Based on my travels in China and 54 countries these past three decades, I see the good that can come from “going there” rather than isolation. I also see the value of idea and best practice exchange, open dialogue, low or no barriers to trade, and of educational exchange. We are all better off when borders and markets and minds are open, when businesspeople and adventurers can travel and explore and learn from each other, and build relationships.

Probably the worst decision in human history was that of the Chinese Emperor Zhu Zhanji in 1434. In that year he issued the Edict of Haijin that closed China off from the rest of the world for over a century. Let’s hope that history is not repeating itself.

Read the full article here