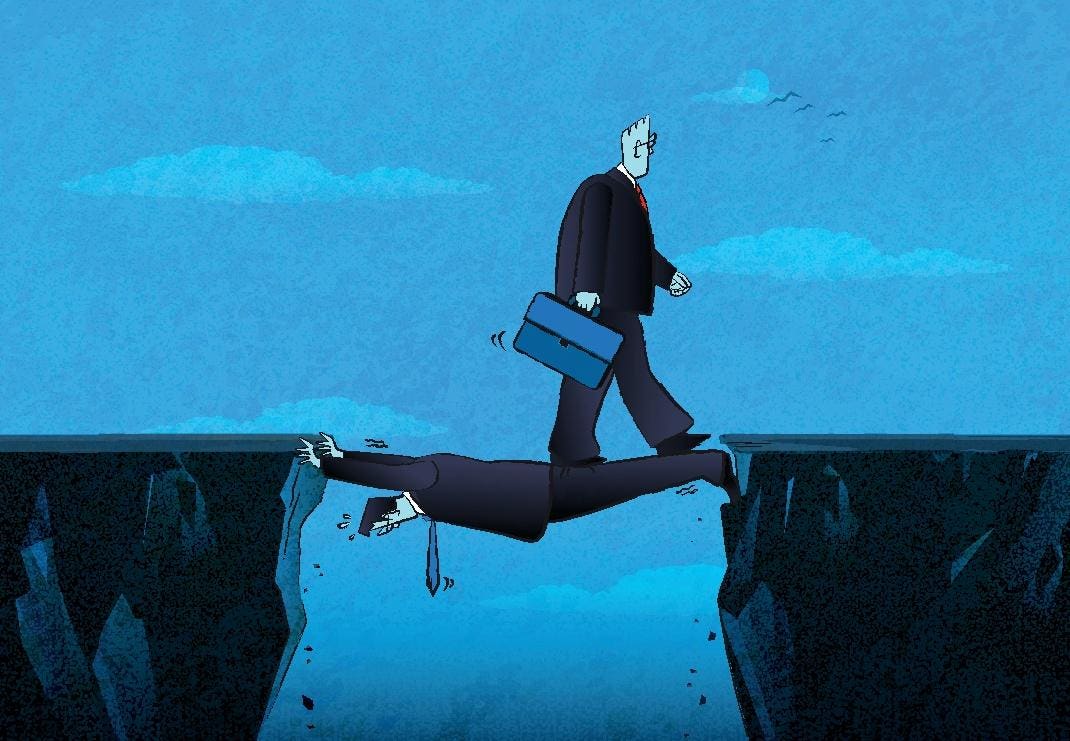

Toxic bosses, toxic meetings, toxic workplace cultures. We are bombarded with twists in negativity and toxicity in the workplace. Today’s Workplaces need teams that collaborate to provide the basis for innovation. I have written on this topic several times. Effective working relationships are built on trust and willingness to call out different opinions by permitting dissent or constructive challenges. But what happens in a team where the leadership and behavior do not align with your values?

The behavior of colleagues may cause you to question their motives. Or the leader in your team is someone who uses their position to assert themselves without respecting different perspectives. The initial charismatic style gives way to a dogmatic approach to decision-making. In these situations, leaders often focus on their perspectives. Where outside views are offered, they are derided, leaving individuals feeling vulnerable. As in any group of humans, team members are incredibly skilled in determining power dynamics. They quickly align themselves with the power base to avoid rejection and humiliation. This approach is a human survival instinct to avoid exclusion and the experience of physiological pain – feelings of exclusion activate the same triggers in our brains as experiencing physical pain. How often do we call out offensive behavior? What determines our willingness to challenge this leadership and potentially face harsh reactions?

As team players, we are socialized into tolerating uncomfortable behavior, not always explicitly offensive, but enough to cause us to stop and double-take on the experience. A great deal of our reactions depends on how we are socialized. Social acceptance and approval often mean we are wired to downplay microaggressions or experiences to stay included as much as possible. When excluded, the reaction induces social agony that registers in the brain as physical pain. Frank Porreca and Theodore Price shared their findings when they recorded brain activity among university students playing computer games. When the participants experienced feelings of being ostracized, the MRI scanners registered activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, the part of the brain associated with physical pain, these experiences in turn increased stress, lowered self-esteem, and minimized our sense of control over our environment, is it any wonder that we do everything we can to avoid exclusion and the sensation of pain? A reluctance to address hubristic behavior and set boundaries becomes self-perpetuating. Where do we draw the line? What happens when a leader mocks your suggestions, or you and no one speaks up? What happens when colleagues criticize someone who isn’t present and can defend themselves? But what happens things get more serious? Does someone make inappropriate comments of a sexual nature or behave in a menacing way or even cause physical harm?

At the end of 2022, the ILO conducted its first global survey on the experiences of violence and harassment at work. It found that one in five people had been the victim of this behavior. The research conducted by the International Labour Organization (ILO), Lloyds Register Foundation (LRF), and Gallup found that almost 23 percent of people in employment had experienced any of the following forms of harassment; physical, psychological, or sexual. Any of the above experiences demonstrate a lack of psychological safety among teams- the ability to call out behavior without fear of criticism or retribution. So what can you do about it? If you are in a leadership observe how colleagues react to negative behavior, your formal authority allows you to set the standard by calling out unacceptable comments. If you have informal power in teams without a formalized leadership position, speak to colleagues on the receiving end of this behavior. Leaders exhibiting excessive hubris are unwilling to hear criticism of their behavior and ideas. They make decisions (sometimes irrational) without valuable insights and input from others and are often perceived as impulsive and reckless. This behavior dissolves boundaries of acceptable behavior, which is needed to build and maintain trust among colleagues. Once this behavior is established, it becomes normalized.

The research from the ILO demonstrated that three out of five victims had multiple experiences of violence and harassment at work. The most common reasons for non-disclosure for all victims were being seen as time-wasters and fearing their reputations would be damaged. While a magic wand doesn’t exist, you can take a stand against the tyranny of politeness, knowing your boundaries and what you will not accept for yourself and your colleagues. Having a clear set of values valid and relevant to your working life makes it far easier to assert yourself when a line has been crossed. Once you set the boundaries, you ensure they are respected and this allows you to steer your career. Being polite does not mean being a pushover.

Read the full article here