Investment thesis

Oil (CL1:COM) prices have been trending lower, mostly on expectations that demand is weak. Stories of continued US production growth, despite the steady drop in drilling activity in the past year also help to provide a sense of complacency regarding global oil production supply growth trends, even as demand growth is seen as being tepid at best. The oil price decline since late September is already having an effect on macroeconomic trends, such as inflation. The recent CPI report produced an October surprise that helped to boost stock markets, as expectations of future monetary easing have been reignited.

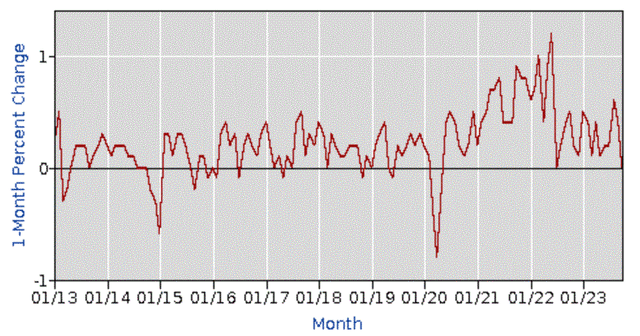

CPI monthly chart (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Energy prices were lower y-o-y by almost 5% based on the CPI report for October. Without the dramatic drop in oil prices, energy costs would have probably been up for the year, and perhaps flat compared with September. In other words, there would have been no inflation surprise to boost the market. Oil prices and to a lesser extent natural gas and other commodities will be the key drivers regarding where inflation will be headed for the remainder of this year and next, thus where interest rates will go as well. The one thing that should be taken into account by investors going forward is that lower interest rates are already baked into current market valuations, meaning that a global oil supply glut is already priced in as well in my view. The supply shortfall scenario and its implications for the markets are not priced in, meaning that this is now a low-reward, high-potential-risk market.

Global supply factors

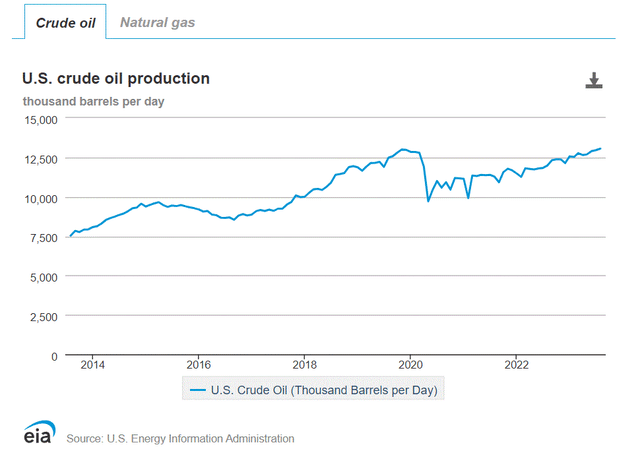

Based on preliminary data, the EIA confirmed that US crude oil production reached new record highs this fall, with 13.2 mb/d. The EIA monthly production report which is more definitive but lags behind by a few months confirms that production is growing at a robust pace this year.

EIA

As of August, US oil production surpassed 13 mb/d, which suggests that the weekly preliminary EIA data is probably accurate.

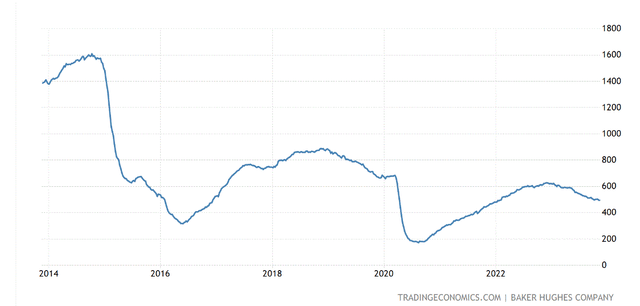

US oil rig count (Trading economics)

As we can see, we are pretty far from pre-pandemic oil drilling rig deployment levels. At some point, perhaps in the not-very-distant future, the continued steady decline in rig activity that we have been seeing for a year now, will most likely lead to a stagnation in production or even the start of the decline of the entire shale industry. It should be noted that the Bakken & Eagle Ford fields are already past their likely all-time production peak. The Permian is the only field that continues to drive upward production momentum for the entire US oil industry.

The US production growth story is in my view more of a sentimental factor affecting the market in the shorter term than a long-term fundamental factor. Current production rates are only about 1% to 2% higher compared with the pre-COVID record highs, therefore it did not add a massive amount of oil onto the market, even as global demand has now surpassed pre-pandemic levels.

Based on the forward-looking EIA Drilling Productivity Reports, US oil production might now be in slight decline for two consecutive months in a row. I expect that if the trend continues and starts to be confirmed on a steady basis by the lagging monthly production reports, the market sentiment is likely to turn to panic mode since growing US production has been the saving grace of the global oil market for almost a decade and a half. The shale patch added about 8.5 mb/d in global production since the shale boom started, which amounts to pretty much all the net gain in global crude oil production for the past decade and a half. It might take about half a year or more after production starts to decline for the market to fully catch on, understand the implications, and fully react, but when it does react, once the implications start to sink in, it will most likely lead to dramatic moves in the oil market.

- Russia export disruption risk.

An almost unnoticed and under-contemplated recent news story that has the potential to have a massive and immediate impact on the global oil supply situation and, thus on the oil market itself is the EU’s most recent sanctions scheme. More specifically, one of the provisions is to try to enforce the failed $60/barrel oil price cap by closing the Danish navigation routes to oil tankers that carry Russian oil without Western insurance. About a third of Russia’s seaborne crude goes through that route, amounting to about 1.5 mb/d. If this was a global supply glut situation and if Saudi Arabia were on board with us to help temporarily plug the gap, this might not be a potentially dramatic situation. Neither one of those two conditions seems to be in place currently, therefore an arguably bad EU decision, and it seems to me that it did not receive much logical analysis before its adoption and has the theoretical capacity to impose chaos on the global oil markets if it is used for its intended purpose. We shall see what comes out of it, depending on what the EU will do in practice, but right now, this is a definite supply disruption risk factor that seems to be flying under the market’s radar.

There are other supply-side risks of disruption, including the ME conflict, where the fighting and tensions can escalate in perhaps unpredictable directions, although in my view the risk of escalation has passed. The Venezuela situation is still an unknown factor. It could lead to a significant increase in global oil supplies, depending on how the continued relaxation of sanctions will develop. Based on OPEC reports, a number of the club’s members like Angola for instance are past their permanent all-time peak in production. It may not be obvious, given the appearance of production controls, but I think that Saudi Arabia is also one of the nations that cannot sustain production at its stated capacity of around 12 mb/d. Its Ghawar field, which historically used to provide about half of its output, was reported to be in severe decline a few years ago. A few of its other fields are also past their peak.

For the past decade and a half or so, there has been no significant increase in global conventional oil output. Most of the increase came from North America’s shale and oil sands resources. There may be some bright spots, as well as some places where production is in decline across the world, but in the absence of continued expansion in North American unconventional oil output, chances are that the global crude oil production capacity is currently in near stagnation mode at best. The EIA’s forward-looking estimates suggest that US production may stagnate as of this fall, so it remains to be seen whether it is the case a few months from now when more definite data will be released.

Global liquid fuel demand is still rising

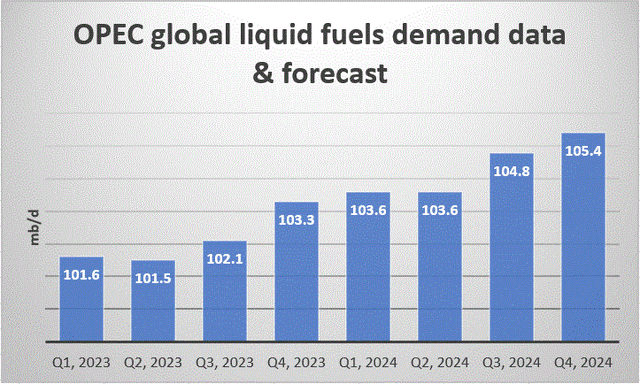

For the demand picture, we have the main institutions providing us with a somewhat unified picture. OPEC suggests that global liquid fuels demand is set to continue growing at a robust pace

Data source (OPEC)

We entered the current quarter with 101.6 mb/d in global liquid fuels supply as of October. As we can see demand is currently over 103 mb/d according to OPEC and it is set to stay above this level for the first two quarters of next year, before we get another upward leap in demand in the second half of 2024. From the fourth quarter of this year to the same quarter in 2024, the world will need another 2 mb/d in new supply to keep pace with demand. OPEC’s numbers suggest we might be in for an oil price spike in the next 12 months.

The IEA on the other hand is forecasting a global liquids surplus of .5 mb/d next year. It also used language in its last report suggesting that demand growth is set to be weak beyond 2024, as the global post-COVID recovery stalls out, while continued EV sales growth will also negatively impact liquid fuels demand. It is unclear at this point what to make of the seemingly growing discrepancy between institutional forecasts. I also find it hard to reconcile how we will have a supply glut this time next year when current production is less than 102 mb/d at the start of Q4, 2023, while demand is forecast to be well over 105 mb/d for Q4, 2024. To make matters even more confusing, the IEA estimates that in September there was a global build in liquid fuels of almost 10 million barrels, even though OPEC’s data would suggest that we have been in a supply deficit situation since at least the second half of this year. Overall, there seems to be a great deal of uncertainty regarding what we should expect from the global oil markets for the rest of this year and next year.

Investment implications:

- Interest rates are unlikely to decline much next year if oil prices start to rise. Market valuations should decline once it sinks in that lower interest rates are not in the cards soon.

The market currently seems to be factoring in lower interest rates going forward based on stock market valuations.

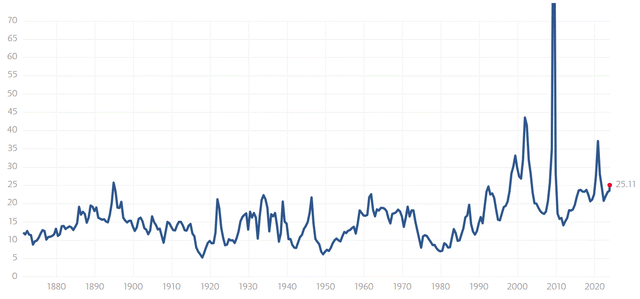

S&P 500 P/E ratio (Multipl.com)

While historically the P/E ratio for the S&P 500 has been around 16, currently it is at over 25. It might be a valuation level that makes some sense if interest rates would be as low as they were in the 2010-2021 period, but not within the current interest rate environment. The continued valuation of the S&P at current levels will only be sustainable if interest rates start to decline in my view. For that to be made possible oil prices need to stay at the current levels or decline further. If oil prices rise significantly higher, inflationary pressures will intensify, which will make it hard to produce a significant reduction in interest rates.

If lower interest rates do not materialize, at some point the market will have to move back towards historical norms. With all else held equal, the S&P would have to decline from current levels of around 4,500 points to about 3,000 points to revert to a historical P/E ratio. I do not foresee such a steep decline to be a realistic scenario for next year, because of other factors, but some realignment toward fundamentals is likely to take place if oil prices rise going forward

- Global economic growth will be curtailed in the absence of continued global liquid fuel supply growth.

Over the years I tried my best to identify a causal relationship between oil supply growth and potential maximum GDP growth. The best that I was able to come up with was the following formula:

1.5% (economic efficiency growth) x (% liquid fuels supply growth x2) = Maximum potential GDP growth.

So, in other words, for a 1% expansion in liquid fuels supply we get a maximum global GDP growth of 3% per year. I should note that the world’s average GDP growth averaged about 3%, while global liquid fuel supplies increased by about 1% per year, therefore the model seems to fit. If liquid fuel supply growth were to drop to zero, it would lead to an annual potential global GDP growth rate of just 1.5%. It should be noted that while the reaction of the market to oil supply shortfalls may be to seek new technologies to improve efficiency, a slower pace of economic growth theoretically tends to slow the deployment of new technologies, given that companies tend to forego investments during periods of stagnation.

Summing up the net effect on the global economy of a hypothetical stagnation of global liquid fuel supply growth, the two resulting trends of higher inflation and lower growth combined would create a classical stagflationary trap. The implications for investors will be nominal stock market gains that will not beat inflation in the longer term. The only way to produce real positive results adjusted for inflation will be to beat the market by timing the market right and by picking investments that outperform the market.

My strategy to cope with this situation is to lean heavily towards upstream oil producers with a proven track record of being able to profit at prevailing average prices, while also sitting on sizable upstream reserves. The largest individual stock holding in my portfolio is currently Suncor Energy Inc. (SU). I also have a significant position in Canadian Natural Resources Limited (CNQ) stock, which is in most ways similar in terms of company profile to Suncor.

If things take a turn for the worse, I also have a sizable position in gold-related investments. I have a position in the SPDR Gold Shares ETF (GLD), Barrick Gold Corporation (GOLD), as well as smaller positions in Wheaton Precious Metals Corp. (WPM), and Silvercorp Metals Inc. (SVM). I also own physical gold. My gold & precious metals positions are meant less to chase returns, but rather to serve as a bit of insurance in case the global economy is destabilized to a greater degree than most of us expect to see it happen.

Overall, I am looking at keeping my positions in any particular stock at around 3% or less to reduce risk. It does not always work that way and it is not wise in my view to be overly rigid, but for the past two years or so, I have been keeping an average of 20 to 30 stock & ETF positions in my portfolio. Furthermore, I tend to avoid buying stocks that are near or at their all-time highs. Chances are that such stocks will have more downside risk than they have continued upward momentum going forward. There are always exceptions but given the current overall investment environment, bargain shopping for stocks or other investment opportunities that are mostly down due to temporary external factors seems like the ideal bargain. Lithium miners might be a potentially good example of this, as I pointed out in a recent article where an arguably temporary decline in lithium prices caused a steep selloff in lithium mining stocks.

Oil is arguably the one commodity that shaped the past century and a half to a greater degree than any other commodity. It will most likely continue to play a determining role in humanity’s future for some decades to come. More immediately, it is likely in my view to play a major factor in interest rate decisions, which in turn will have a major impact on markets. It remains to be seen which way the global liquid fuel supply/demand balance will break. At the moment, there are several conflicting data points as well as forecasts that make it hard to figure out. In the next few months, we should most likely see some degree of validation of either view of an oil supply surplus or deficit, which will in turn indirectly dictate the direction of markets. One thing that should be taken into account at this point is that when we look at P/E ratios, an oil market surplus is already baked into expectations in the form of lower resulting interest rates, while the supply shortfall scenario is not, therefore I believe this is a limited upside market, with outsized downside risk.

Read the full article here