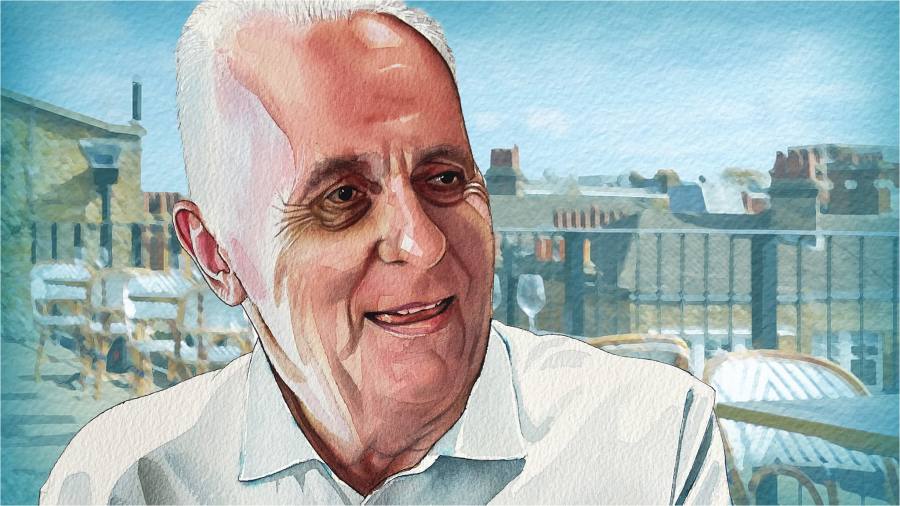

It is a gloriously sunny day as I squeeze into the elevator of the cheery six-storey building that houses The Conduit, a trendy members’ club in London’s Covent Garden for self-appointed “changemakers”. The man I’m here to meet, Mark Malloch-Brown, has taken many guises during a protean career in which the one constant has been the promotion of liberalism, democracy and globalisation — ideas that are now under siege worldwide.

In pursuit of his agenda, he has adopted the roles of journalist, administrator, consultant, spin-doctor, diplomat and government minister. Now, a few months shy of 70, he is running the Open Society Foundations, a grant-making body founded by George Soros, a man whose adherence to liberal values has generated a vicious backlash partly explained by antisemitism.

But that’s not all. The Open Society is itself under attack. A generation of nationalist leaders from Hungary’s Viktor Orbán to India’s Narendra Modi have become less tolerant of outsiders stirring up civil society. Conspiracy theorists have blamed Soros for everything from fuelling the Arab Spring to funding Donald Trump’s prosecution.

Malloch-Brown sees the vilification as part of a broader backlash. “I think it’s no accident that when Globalisation 101 hit the buffers, that’s when democracy stumbled as well,” he says when I make it up to the airy rooftop restaurant.

Developing countries are less willing to accept lectures from a west whose “double standards” have been exposed on Covid vaccines and climate change, he says. “The whole soft paraphernalia of liberal interventionism is in retreat.”

We order sparkling water. Malloch-Brown, a regular at The Conduit, looks comfortable in his tall frame, dressed in a tieless shirt, jacket slung over a chair.

There are big issues to discuss, including upheaval and generational change at the Open Society, but there’s time for a cheap shot first. Malloch-Brown was made a Sir for his service at the UN, which culminated in him becoming deputy secretary-general, and gained a Lordship in a two-for-one deal with his 2007 appointment as a minister in Gordon Brown’s government. Isn’t the whole honours system a farce, I suggest, probing m’Lord’s left-of-centre reputation.

“It is a farce,” he responds disarmingly, exuding the sort of charm that comes with a first-class education and an honour or two safely in the bag. “I’m a Lord and a Sir, though you’d be hard-pressed to find me ever using the title. Other than the odd airline upgrade and better restaurant table, it’s difficult. I’ve sort of been tempted to sort of step down entirely,” he says, less than emphatically.

That temptation happily resisted, and an excellent table in the shade secured, we scan the short menu. The pizza oven is broken so it’s just got shorter. “The cod is always pretty good. The poussin as well — a fancy name for chicken,” he says, naming two of the four surviving mains.

He settles for Kent asparagus followed by Cornish cod with “rope grown mussels”. I opt for burrata with normally grown tomatoes and the spatchcock poussin, a dish I’ve recently charred to a cinder after employing a technique involving a brick and a frying pan.

The menu promises “a nature-forward focus that supports and highlights biodiversity and reforestation”. I’m just glad to be doing my part. We settle on a glass each of Sauvignon Blanc shipped all the way from South Africa.

I want to talk about the waxing and waning of internationalism, a trend in which Malloch-Brown has been more than a bit player. In a review of his 2011 book The Unfinished Global Revolution, Peter Preston, former editor of the Guardian, called him “Lord Global”.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, globalisation was already in retreat. “This apparently happy partnership of democracy and free markets couldn’t deliver,” he says. “While the political stuff was arguably meant to be a race to the top, the economic stuff was a race to the bottom.”

Our starters arrive. The asparagus is sprinkled with toasted almonds and swamped in roasted peppers and endive. My burrata is creamy deliciousness, complemented by the wincing tartness of the tomatoes.

Malloch-Brown was at the UN from 1999 to 2006, during what he calls a “golden era” under Kofi Annan, the quietly spoken Ghanaian whom he considers one of the two great secretaries-general, alongside Dag Hammarskjöld.

“It was peak UN. The mood was so different. When I look at the doctrines we were able to promote with a straight face, like R2P,” he says of Responsibility to Protect, by which in 2005 the UN committed to never again tolerate mass atrocities. “R2P was the signature idea of its times because of apparently falling borders and shared sovereignty,” he says, picking at his asparagus, more invested in the conversation than the food.

The doctrine came a cropper on virtually “its first outing” in 2011 when “overenthusiastic western handlers” from the UK and France used R2P to justify the overthrow of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi.

“They basically screwed it before it began. The Brits slipped it in at the eleventh hour on a Friday evening,” he says of the resolution approving a no-fly zone over Libya. “According to legend, there was no Russian desk officer either in New York or Moscow sober enough to read it.”

Globalisation did not founder because of drunk Russian apparatchiks or overreaching Europeans. But R2P was the high point for what Malloch-Brown calls “the global project”. In his 2011 book he had predicted “a lot more liberalism, more human rights”. Looking back over a decade in which nationalism and authoritarianism have gained ground, he says: “Obviously Lord Global got that wrong.”

His plate looks like a bomb site. In fairness, I have been asking all the questions. Our mains arrive. We’ve ordered chips and a side of broccoli on which sauce has been squiggled in Jackson Pollock freehand.

Malloch-Brown was born in 1953 and the family settled in a Sussex village. His parents had met during a “wartime romance”. His South African father, a Rhodes scholar, had cut short his studies at Oxford to join the war effort and his British mother was a navy Wren.

“My father had been a scholarship boy. He’d grown up in a farming town in the Western Cape,” he says. “He was absolutely determined that I was going to have the privileges he hadn’t.”

The young Malloch-Brown went to prep school and from there to Marlborough boarding school. His father was by now a commercial lawyer. “And then, sadly, he promptly dropped dead,” Malloch-Brown says, the comic timing masking the hurt.

His mother, who went on to teach troubled children, scrimped to ensure that her only child fulfilled her late husband’s wishes. She’s still sharp and fascinated with world events at 101, he says. He continued at Marlborough as what he calls “the poor country mouse”.

He is attacking his cod with more gusto. My poussin, evidently prepared sans brick, is seared to a nice crisp finish.

He had been brought up on John Buchan novels and stories of Jock of the Bushveld, “about a dog that ran wild in the bush”. He spent his gap year in Africa, having developed “this absolute curiosity to go to the continent of my father’s birth”.

In South Africa, the 18-year-old worked on the railway yards, mainly night shifts, in a job reserved for whites. It was 20 years before the end of apartheid. But the railwaymen could already sense coming change. “I think back on these conversations I’d have at night with them in the middle of a coffee break, when they would talk about their fear of the black majority.”

He’d hear similar stories from Cambodians when he wound up working on the Thai-Cambodian border for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees a few years after graduating from Cambridge and Michigan universities. Middle-class Cambodians fleeing Pol Pot’s regime talked “in the same apocalyptic terms about the revolution of the underclass against them”.

Neither the South African railway workers nor the Cambodians were “elites themselves” but both had “some kind of economic position that was going to be destroyed”. Today, Malloch-Brown senses a parallel with supporters of Donald Trump. Though he disavows the politics of Republican senator JD Vance, he says books like his Hillbilly Elegy are the only ones “that come close to capturing” this sense of fear and dislocation among people buffeted by forces they can’t control.

We nod through the suggestion of a second glass of Sauvignon Blanc. Submitting my expenses later, I notice we weren’t charged for the wine — evidently another bonus of the honours system.

In Thailand, Malloch-Brown supervised the construction of refugee camps for half a million people. At 26, he became an expert on bamboo houses, water and food supply chains, and latrine construction.

There was a camp for the Khmer Rouge and another for those fleeing the Khmer Rouge. “I had a white Swedish helicopter to jump from one camp to the other,” he says. One day, he got an urgent call. “Some hopeless American Christian NGO had organised a football match between the two camps without telling me. I raced down to the makeshift football field, and we survived without incident. If it had been an away game at the Khmer Rouge camp, I think lives would have been lost.”

Back in England, he worked for The Economist, his second stint there. He missed out on selection as a parliamentary candidate for the Social Democratic party. But he was itching for adventure. “No, it’s too small. I can’t, I won’t,” he remembers of the thought of being trapped in Britain. “My curiosity needs a bigger stage.”

He found what he was looking for at Sawyer Miller, a consultancy busy exporting the techniques of US political campaigning. With a gonzo confidence, he advised the victorious 1988 No Campaign in Chile that saw off General Augusto Pinochet. In Peru he worked on the presidential campaign of novelist Mario Vargas Llosa, who lost to Alberto Fujimori, a proto-populist who conducted his rallies from the back of a tractor.

He helped Cory Aquino’s “yellow revolution” which swept away Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos in 1986. Democracy was winning. For a reality check, look no further than the Philippines today, where Bongbong Marcos, Ferdinand’s son, was last year elected president.

Wasn’t democracy meant to sweep out this stuff? “We started from a high point of 130 democracies. So it’s not surprising that the bowling pins have been getting knocked over,” Malloch-Brown says, alluding to consolidation of power by authoritarian leaders who have learnt to game elections and the return of old-fashioned coups in regions such as west Africa.

Working with newly elected leaders in the 1980s and 1990s, he became frustrated at international financial institutions whose foot-dragging, he felt, deprived leaders of the money they needed to consolidate democracy. When he was offered the position of spin-doctor-in-chief (vice-president for external affairs) at the World Bank, he jumped at it.

“I decided that this was a brilliant opportunity to become the revolutionary inside the house,” he says, putting the best gloss on his move inside the institutional tent. Under James Wolfensohn, the bank anyway was more progressive than the IMF, he says, which persisted in imposing ruinous austerity in Africa and then Asia.

At the UN Development Programme, which he ran from 1999 to 2005, his job more happily was to dole out cash. He oversaw the creation of the Millennium Development Goals, which among other things aimed to eradicate extreme hunger and poverty by 2015. Both fell. Neither was eradicated.

After Sérgio Vieira de Mello, a rising UN star, was killed in a 2003 bomb attack in Iraq, Malloch-Brown was left as the “remaining Young Turk”. Kofi Annan made him chef de cabinet and then deputy.

The secretary-general was one of many father substitutes. “My wife has observed that I migrate towards older men,” he says. (He married his American wife Patricia in 1989 and they have three daughters and a son.)

“Fathers in loco” have included Anglican bishop and polar explorer Launcelot Fleming, who mentored him after his father’s death, Wolfensohn and the now 92-year-old Soros, whom he has known for 35 years. “There is a bit of a pattern of which George is probably the last.”

The waiter offers dessert. Malloch-Brown plays along with the FT’s preference for leisurely lunches. “Just to linger on a bit, I wouldn’t mind Yorkshire rhubarb and cream,” he says. When I say I’ll skip dessert, he beats a retreat. “To be honest, I never have dessert. Let me just have a filter black coffee.”

At the Open Society, he has to manage the transition after Soros’s decision to hand over control to his 37-year-old son, Alexander. Successions rarely go well, Malloch-Brown notes. “Alex and I are consumed with ‘how do we make sure this foundation retains its founder’s DNA?’”

His appointment as Open Society president in 2021 was not without controversy. “I’m very conscious that probably the average age of my colleagues is half mine and that I can easily come across as a silly old buffer.”

A few weeks after our lunch, the Open Society announces swingeing job cuts, explaining its decision in a non-informative press release that confirms Malloch-Brown’s description of foundations as “black boxes”. Scouring my notes later, I see he talked about “strategic opportunism” and “patient capital”, phrases repeated in an official announcement that said changes were necessary “to counter the forces currently threatening open and free societies”.

To me he hints at internal conflict in an organisation where Soros’s old-fashioned liberalism may not always sit easily with the identity politics of younger generations. “There’s so much for progressive people to fight for without vacating the battlefield and being in some strange, doctrinal lockdown,” he says. “It’s a time when Trump is threatening a comeback in the US and [Jair] Bolsonaro lost by a point and a half in Brazil,” he adds of the urgency of keeping the bigger issues in focus.

Despite everything, he says, he retains faith in a world and set of values that seem to be slipping away. “Authoritarianism has even less of an answer. It doesn’t have the depth of a policy offer that thoughtful, social-democratic-type governments have.

“We’re not in a partisan political fight. But we are in a fight, as George Soros likes to say, between open and closed societies. Closed societies ultimately feed on themselves. They don’t have the capacity for renewal,” he says, draining his coffee.

“Look, I’m like a Ukrainian general. My offensive hasn’t yet broken through. But I feel that right is on our side, ideas and history are on our side.”

David Pilling is the FT’s Africa editor

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Read the full article here